Winfried Bruenken (Amrum), CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1886, William Leonard Hunt, a Canadian showman better known by his stage name “The Guillermo Farini”, published a sensational travelogue claiming he had stumbled upon strange stone ruins deep in the Kalahari Desert. Newspapers of the time seized upon his story, dubbing it the “Lost City of the Kalahari.”

Since then, the legend has refused to die. Expedition after expedition has traveled Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, seeking to uncover a hidden metropolis, and even invoking comparisons to Atlantis, the ancient Greek myth of a drowned utopia. TV crews, modern explorers, and internet sleuths still revisit the story every decade or two, hoping modern technology can prove it true.

And yet, despite all the hype, archaeologists have found no evidence of such a city. Instead, what emerges is a far richer, more complex truth which includes misread geology, forgotten colonial showmanship, and overlooked African histories of settlement, art, and survival in the Kalahari.

Source: Advanced Pre-Ice Age Civilization Discovered in the Kalahari Desert – African Explorer Magazine

Historical Origin Of The Legend

The story begins with William Leonard Hunt (1838–1929), a Canadian-born circus showman and adventurer. Performing under the name Guillermo Farini, Hunt was famous for daring acrobatics and theatrical flair. In the mid-1880s, he turned his attention to southern Africa, traveling into what is now Botswana and Namibia.

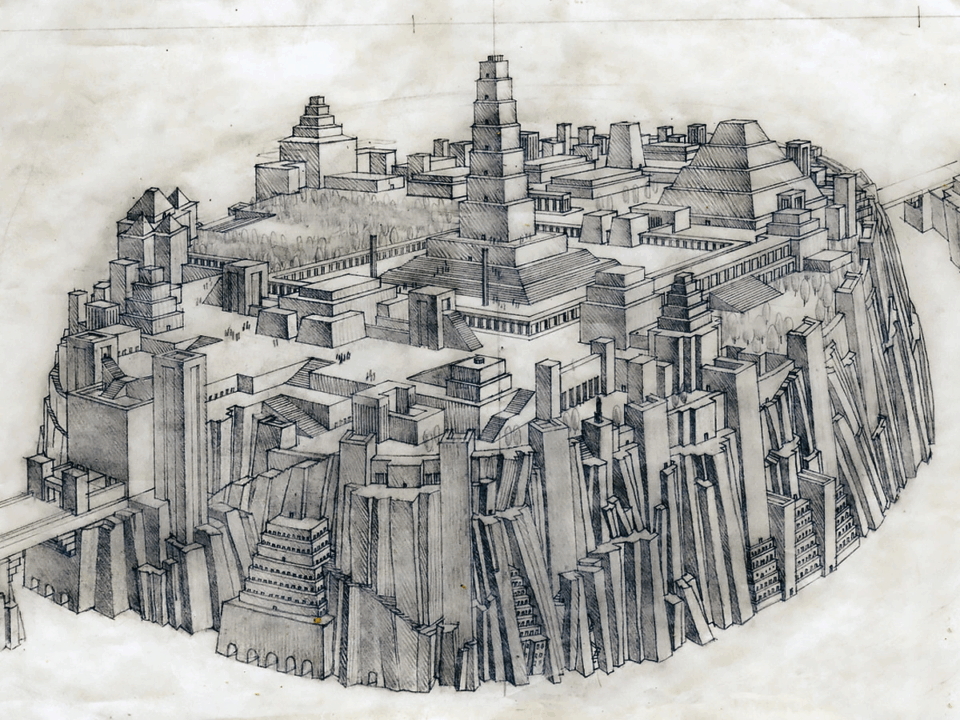

In March 1886, Farini presented his paper “The Ruined City of the Kalahari” to the Royal Geographical Society in London. He described “half-buried walls,” “stone corridors,” and “ruins of massive structures” deep in the desert. Illustrated sketches and dramatic retellings captured the Victorian public’s imagination.

In his book, Farini describes the ruins as:

A half-buried ruin – a huge wreck of stones

On a lone and desolate spot;

A temple – or a tomb for human bones

Left by men to decay and rot.

Rude sculptured blocks from the red sand project,

And shapeless uncouth stones appear,

Some great man’s ashes designed to protect,

Buried many a thousand years.

A relic, may be, of a glorious past,

A city once grand and sublime,

Destroyed by an earthquake, defaced by the blast,

Swept away by the hand of time.

But early on, doubt surrounded his claims. Unlike rigorous explorers of his time, Farini was an entertainer. His accounts often veered toward spectacle, leaning more on performance than on verifiable maps or detailed coordinates.

19th- and early 20th-century explorers often projected their cultural expectations onto African landscapes. Instead of recognizing long histories of indigenous occupation, artistry, and survival, they imagined vast “lost” civilizations hidden from view, civilizations that required “discovery” by Europeans to be acknowledged.

Expeditions And Search History

Following Farini’s account, explorers returned to the desert time and again, each hoping to confirm the legend.

1920s–1930s: Several expeditions by South African and European adventurers were conducted unsuccessfully. Some claimed to have seen “walls” or “ruins,” but later research suggested these were natural rock lines formed by erosion.

1950s: More organized efforts, including the work of journalist and popular South African writer Lawrence G. Green, revived interest.

1980s–90s: Renewed expeditions combined aerial photography with ground searches. Again, no verifiable ruins were identified, only striking geological features.

2016: The TV show Expedition Unknown with Josh Gates devoted an episode to the Kalahari myth. Using remote sensing and on-the-ground scouting, the team scouted parts of Botswana and Namibia. Their conclusion: no credible archaeological evidence for a city exists.

Media fascination with lost cities tends to overshadow authentic archaeology. Viewers are more likely to remember the spectacle of a dramatic desert search than the quieter, detailed work of archaeologists mapping ancient rock art or dating occupation layers at sites like Tsodilo Hills.

The closer one looks for the city, the more it disappears. What remains constant is not ruins, but the story, retold, repackaged, and made profitable by those who market exploration as entertainment.

What Archaeology And Palaeo-Environmental Science Show

To understand the Kalahari, we must leave behind myths and look at the evidence.

The Kalahari Desert is not a barren wasteland, but a semi-arid ecosystem that has supported human life for thousands of years. Archaeological and palaeoenvironmental research shows a long timeline of settlement, mobility, and adaptation here.

The Tsodilo Hills in northwest Botswana, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, host more than 4,500 rock paintings, some dating back 1,200 years, alongside artifacts indicating occupation as far back as 100,000 years. Excavations at the White Paintings Rock Shelter have revealed stone tools, pottery, and evidence of changing water availability. Far from a “lost city,” Tsodilo represents continuous African creativity and resilience.

Source: Tsodilo Hills Tours | Destination Travel Guide

Environmental Shifts

Palaeoenvironmental data reveal that the Kalahari has shifted over millennia between wetter and drier phases. Ancient river systems, such as the Makgadikgadi Pans, once held massive lakes. Archaeologists studying shoreline deposits and diatom (microscopic algae) remains suggest that humans inhabited these areas during wetter climatic phases, moving seasonally with water access. This pattern explains scattered stone alignments or earthworks that explorers misread as “walls.”

Erosion and Misread Rock Formations

Geologists note that many “ruin-like” formations, particularly rectangular blocks reported by adventurers, are results of jointed dolerite outcrops, natural fractures that mimic masonry. Without training, early explorers mistook geology for architecture.

Dating and Methodology

Unlike sensational explorers, archaeologists use rigorous methods such as radiocarbon dating and optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to establish chronology. No scientific paper has ever confirmed urban-scale stone structures in the Kalahari. What has been confirmed are hunting camps, rock shelters, ritual sites, and tool-making areas, offering a portrait of dynamic, resilient lifeways over thousands of years.

Why The “Atlantis” Framing Sticks

Why do stories like this endure, when evidence says otherwise?

Part of the answer lies in Western romanticism about “lost civilizations.” Atlantis, first penned by Plato as an allegory, has long been reimagined as a literal truth. Casting Africa as the stage for such myths gave colonial-era writers license to recast the continent as “mysterious,” awaiting European discovery.

There’s also the question of erasure. Real African achievements, from Great Zimbabwe to the kingdoms of Mali, were long ignored or misattributed. Imaginary “lost cities” often got more attention than documented African civilizations.

The yearning for a reclaimed past, the allure of “lost origins,” and the frustration of seeing African cultures distorted or denied. The narrative of a Kalahari Atlantis substitutes fantasy for truth, but it also shows how colonizers controlled the story.

As Afrocentric scholars such as Molefi Kete Asante argue, recovering Africa’s past is not about chasing mirages but about “centering African people in African history.” Recognizing Tsodilo Hills art, San traditions, or Bantu migrations matters far more than indulging European fables.

Contemporary Claims, Media, And Responsible Reporting

Even today, viral stories about the “Lost City of the Kalahari” resurface.

Take the 2016 Expedition Unknown search: despite its scientific gloss, the show relied on dramatic visuals and inconclusive scans. Peer-reviewed follow-ups? None. Similarly, online claims about “Atlantis in Botswana” fail when checked against established archaeology.

So how can readers evaluate such claims?

- Check the source: Is it a peer-reviewed journal (e.g., Journal of African Archaeology) or a clickbait site?

- Look for data: Does it mention radiocarbon dates, stratigraphy, or excavation reports?

- Ask who is speaking: Is there input from the University of Botswana, local museums, or respected southern African scholars? If not, be wary.

By becoming critical consumers, diaspora readers can avoid being misled by myths that diminish African history. Responsible reporting means amplifying real African voices, citing research institutions, and not exoticizing the continent.

The Kalahari Atlantis makes for a great adventure story. But after nearly 140 years, no ruins, temples, or lost empires have been found, only eroded rocks and a trail of colonial imaginations.

Anand Subramanian is a freelance photographer and content writer based out of Tamil Nadu, India. Having a background in Engineering always made him curious about life on the other side of the spectrum. He leapt forward towards the Photography life and never looked back. Specializing in Documentary and Portrait photography gave him an up-close and personal view into the complexities of human beings and those experiences helped him branch out from visual to words. Today he is mentoring passionate photographers and writing about the different dimensions of the art world.