Hadraawi, Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Mohamed Ibrahim Warsame Said, widely known by his childhood nickname Hadraawi, was one of the greatest Somali poets of all time. He was certainly the most famed Somali poet since the mid 1900s. He will remain the Somali poet of this century and beyond.

As an adult, he was a prolific producer of poems and songs, a known soldier of the voiceless and a fierce voice of poetic political critique in Somalia, especially against the postcolonial elite who have ruled the country since independence in 1960. He was an advocate for peace in the war-torn country.

As a 10-year-old student of Arabic, however, he was better known for chatting to his fellow students than learning the holy Koran with them. His tutor labelled him “Abu Hadra” (the father of talk), which, for Somalis, became his widely used nickname Hadraawi.

He composed poems about such crucial themes as a dictatorship, social justice and family values. His most distinguished and, perhaps, best poem will be remembered as Hooyo (Mother) which later became a popular song for all mothers.

His voice resonated with Somalis living throughout the world and he was fêted at international literary events. But it was at home in Somalia, the land of poets, that his voice lives on in people’s minds.

Somalis have been blessed with poets of all sorts and, in the popular imagination, it is often said through every 50 years Somali society produces a tremendous poetic talent. This was the case since the precolonial period. British explorer Richard Burton, who travelled through the Somali territory in 1854, described the Somalis as “a nation of poets”.

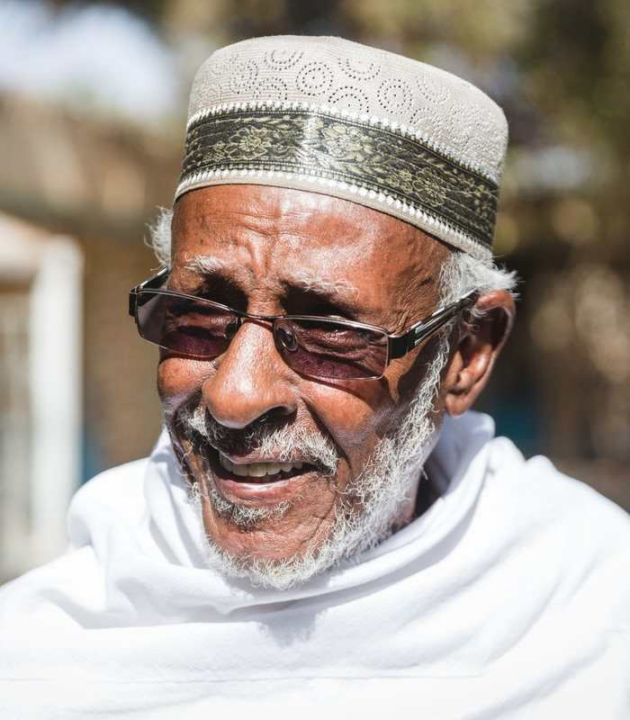

Hadraawi in 2006. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Born in 1943 into a pastoralist family on the nomadic outskirts of Burco, the second largest town in the former British protectorate of Somaliland, Hadraawi began his childhood in a critical place at a critical time. It was an era of nationalist revival when the Somali people instigated demands for freedom and independence from various colonial powers.

From the period after the second world war in 1945, Burco was a centre of protests against British colonial rule. It produced activists and intellectuals like Mohamoud Jama “Uurdooh” who – using petitions to complain about injustices – became an albatross around the neck of the British. Young Hadraawi was influenced by their anticolonial activities.

He started composing poems as a child. He believed he was about five or six when he first composed what would become his epic, Hooyo, about mourning the passing of his mother Kaha Jama Bihi.

Five years later, his uncle took the orphaned Hadraawi to Aden, Yemen, on the other side of the Red Sea coast. Aden, under British colonial rule, was a hub for diasporic (northern) Somalis who lived side by side with Arab, Indian and Jewish communities.

It was in cosmopolitan, multicultural Aden that Hadraawi earned his nickname. As was the custom for Muslim societies unaffected by colonial sway, his uncle Ahmed Warsame Said enrolled him into a school to learn the holy Koran from the heart.

After also completing a modern education, Hadraawi became a teacher in Aden. During this time, he furthered his poetic abilities by composing a Somali play called Hadimo (conspiracy). The awful assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the great Congolese pan-Africanist, at the hands of colonialists also affected Hadraawi. He was also inspired by the pan-Arabism of Gamal Abdel Nasser, the late Egyptian ruler.

Hadraawi in 2018. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1967, seven years after former British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland gained independence and merged into the Somali Republic or Somalia, Hadraawi moved from Aden to Mogadishu, the lively capital city. Here many sought a sanctuary from violent (post)colonial conflicts in regions like Aden.

He continued his professional teaching in a school in Lafoole outside Mogadishu and became a teacher at the National Teacher Centre there, which had an academic partnership with universities in the US.

Hadraawi found Lafoole a better place for intellectual stimulation, producing many of his important earlier plays and poems, which were mostly poetic missiles against the postcolonial elite and how they blindly followed in the footsteps of the departed colonial rulers – who ruled by corruption and authoritarianism.

He addressed some of his poems to his great friend and colleague, the late Mohamed Hashi Dhama – or Gaariye and, together, they composed a series of poetry to awaken the consciousness of Somali society to the paradoxes of postcolonial rule.

In 1969 the elected civilian government of Somalia was easily overthrown in a coup by armed forces. In 1973, four years into military rule, Hadraawi was silenced. His room at Lafoole college was raided one night. The military rulers were no longer accepting of his subtle but distinct criticism against their rule. They detained him at the house of a district commissioner in Qansaxdheere, a remote area in southern Somalia. Here he spent five years of detention.

He was released in 1978 and taken to the presidential palace to meet General Mohamed Siad Barre, the leader of the military junta. Barre told him bluntly that he could have been languishing in prison like others, and should thus consider his detention a favour.

Hadraawi accelerated composing his critical poems in the face of official censure and even when the oppression of dissenting voices increased. A few years later, already fed up, he fled to neighbouring Ethiopia to join the Somali armed opposition groups based there.

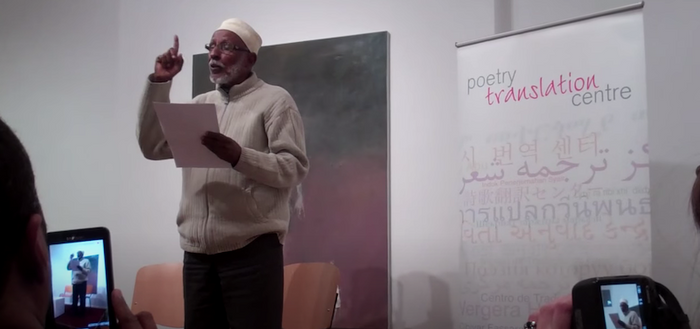

Screencapture of Hadraawi reading ‘Clarity’, Watch original video

Unusually for a poet, Hadraawi played the role of a commanding officer of the Somali National Movement, a politico-military front dominated by his Isaaq clansmen. He was one of the few poets who disseminated anti-regime poems through Radio Halgan, the front radio station. But he left the movement after it was initially embroiled in a leadership crisis.

Hadraawi decided to leave for Europe and stayed in the UK for most of the 1990s, when Somalia collapsed institutionally, economically and politically. But his message of change for the better remained the same, travelling through Europe and north America, addressing the Somalis living there.

In 2003, he carried out a popular peace march in southern Somalia, leading a group of singers and poets to local communities to promote peace. Today these areas are ruled with an iron fist by insurgent group Harakat Al-Shabaab Al-Mujaahidiin.

In the early 2000s, Hadraawi moved back to his childhood town of Burco. The once talkative child had become a careful listener, a calming force to those he met. He remained bedridden in Burco until he was moved to Hargeysa, the capital of Somaliland, where he passed away. A huge crowd, public and politicians alike, attended his funeral.

Writing about Hadraawi’s passing, the Somali novelist Abdourahman Waberi wrote – and I translate from French – that

Never has the death of a man or a woman aroused so much emotion in the vast Somali-speaking world.

Waberi is right. Hadraawi was once called “the Shakespeare of Somalia” by the BBC. Many Somalis counter that Shakespeare was indeed the Hadraawi of Britain. Hadraawi was part of a decolonising force that provoked Africans and Arabs to wake up and counter imperial mantras.

He will be remembered for his prudence and perceptive poetry. His poems will remain in the minds of Somali and non-Somali lovers of poetry for generations to come.