Photo by Bave Pictures

When it comes to achieving racial diversity, music education at the university level in the U.S. still has a long way to go.

One of the leading professional organizations, the Society for Music Theory, put it bluntly in 2020: “We humbly acknowledge that we have much work to do to dismantle the whiteness and systemic racism that deeply shape our discipline,” the group wrote.

The focus on White, male Europeans in textbooks and music selected for study has been called into question by countless scholars and practitioners because of music education’s deep roots in anti-Blackness.

In recent years, the simplest solution for music professors has been to find nonwhite classical composers and use their work on a program or concert to demonstrate the school’s commitment to diversity. One person whose work some professors have used in such a way is Florence Price. A composer and music teacher who died in 1953, Price is considered to be one of the first Black female musicians with mainstream appeal.

But in my view as one of only a few Black scholars in the field of music theory, such diversity efforts often serve only to reinforce the whiteness and maleness of the system.

Ethnomusicologist Dylan Robinson calls these efforts “additive inclusion” in that they give the impression of making positive change but serve only to maintain an overemphasis on the work of White male Europeans.

Black female composer, Florence Price. Public Domain

In 2020, music theorist Megan Lyons and I did an analysis of the seven most common undergraduate music theory textbooks in the U.S.

We wanted to establish a baseline of the racial and gender makeup of the composers represented in the books to see what teachers were offering to our students as the most important music to consider in the undergraduate music major.

Music theory courses, usually spread over four or five semesters, are often considered the most crucial aspect of the major, and theory textbooks are presented as authoritative sources that outline the essentials of the discipline.

Representative titles include “Harmony and Voice Leading,” “Harmony in Context,” “Harmonic Practice in Tonal Music” and “Concise Introduction to Tonal Harmony.”

Looming large in these textbooks is the word “harmony,” the sound that is heard when two or more instruments or voices sound together, though in a global context the term has other meanings as well. What is considered harmony in the U.S. is based on European notions of tonality, pitch, scale, mode, key and melody.

The three composers the books most commonly represented were Germans Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven and Austrian Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

We found that of the nearly 3,000 musical examples cited in the textbooks, only 49 were written by composers who were not White and only 68 were written by composers who were not men.

On rare occasions those two subgroups overlapped, as with Florence Price. Only two examples were written by Asian composers.

All told, almost 98% of the musical examples were written by White men who mostly spoke German, and these seven textbooks represented about 96% of the market share.

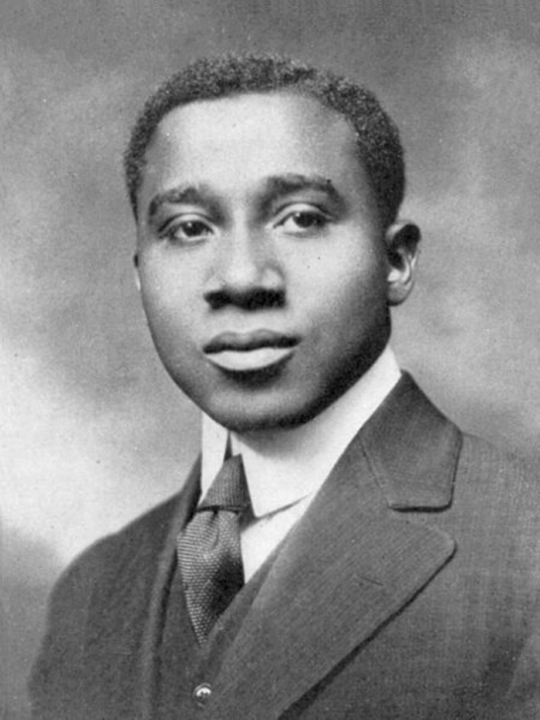

Left out of textbooks are the many African American musicians who contributed significantly to American music, such as classical composers Nathaniel Dett, James Reese Europe, Julia Perry and Clarence Cameron White.

Also generally excluded were nonclassical genres like jazz, blues or bluegrass, or contemporary popular music such as hip-hop, soul or punk.

Composer Nathaniel Dett, 1910s. Public Domain

American music academies generally reflect the social norms of the day. Anti-Blackness was commonly accepted in all music institutions until well into the 20th century through the eugenics of music pedagogue Carl Seashore, the White supremacy of the composer-pianist John Powell and the racism of music theorist Heinrich Schenker.

In her 2019 master’s thesis “A Message of Inclusion, A History of Exclusion: Racial Injustice at the Peabody Institute,” violinist Sarah Thomas details a common American story of racial angst in higher education.

Thomas focused on the Peabody Institute, founded in 1857 in Baltimore, Maryland and the oldest U.S. music institution, and its board members’ letters about the possible admission of Black pianist Paul Brent.

In July 1949, Peabody President William Marbury wrote the school’s board of directors and reminded board members of the school’s unofficial policy at the time:

“We are brought face to face with the issue whether to modify our long-standing rule against the admission of negro students,” Marbury wrote.

Once the issue was put to a vote, only one board member, Douglas Gordon, openly opposed admitting Brent and cast the lone dissenting vote.

“It seems to me that it would be a great mistake to change the present policy,” Gordon wrote. “In our climate the presence of negroes can to some be extremely offensive.”

Though Brent was admitted and became the first Black student to enroll at Peabody, the abhorrent views of Gordon still remain present today in more subtle forms.

Interior stairway of the Peabody Institute, Baltimore, Maryland. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The study of jazz is one such example of racial exclusion.

Generally considered a Black musical genre, jazz is now part of most music educational institutions, but is virtually always separate from the mainstream music major.

In a few cases, students are able to major in jazz. But in most cases, if a student wants to major in jazz, there are very alternatives to majoring in classical music while playing jazz on the side.

Citing declining enrollments for music majors across the country, the College Music Society in 2014 published a manifesto for change to the undergraduate music major.

It deemphasized music and methods of the Western canon while emphasizing the need for students to engage with music from different cultures and with new technologies.

This change has taken many forms.

Musicians are rethinking their curricula to treat all music of the world on equal footing as the European standards.

Piano proficiency and European language requirements are being reconsidered – in some cases cast aside – by music institutions. Other schools are creating new music majors for those working with digital sound and sound design, or for those studying popular genres such as blues, rock, metal and country.

Academic work in music is changing as well, and students can now at times get credit for work outside of traditional paper writing.

It’s my belief that the sooner we musicians, irrespective of our own identities, can face up to our racial segregationist past, the sooner we can all reap the benefits of our nation’s unique musical diversity.