“If a race has no history, it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.”

–Carter G. Woodson

Why the centennial matters

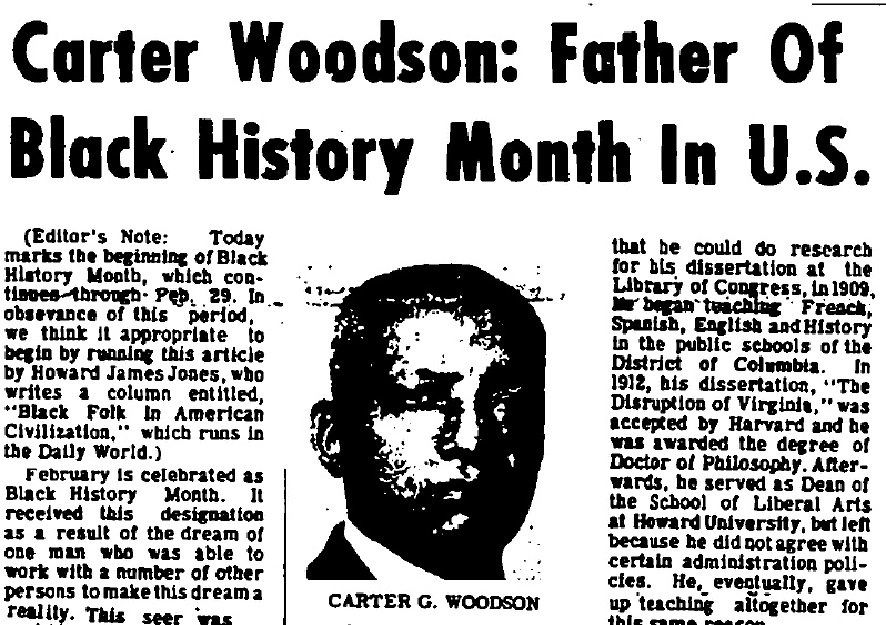

When Carter G. Woodson organized Negro History Week in 1926, he intended a focused antidote to historical erasure. One hundred years later and under ASALH’s 2026 theme “A Century of Black History Commemorations”, communities across the United States and the African diaspora are asking: what has changed, and what still needs doing?

The 2026 centennial is not merely retrospective. ASALH frames the year as both commemoration and a strategic push for institutional permanence in education, archives, and museums. Major public institutions and universities are using the centennial to connect archival research to classroom adoption and to press for sustainable funding.

Why Woodson started Negro History Week

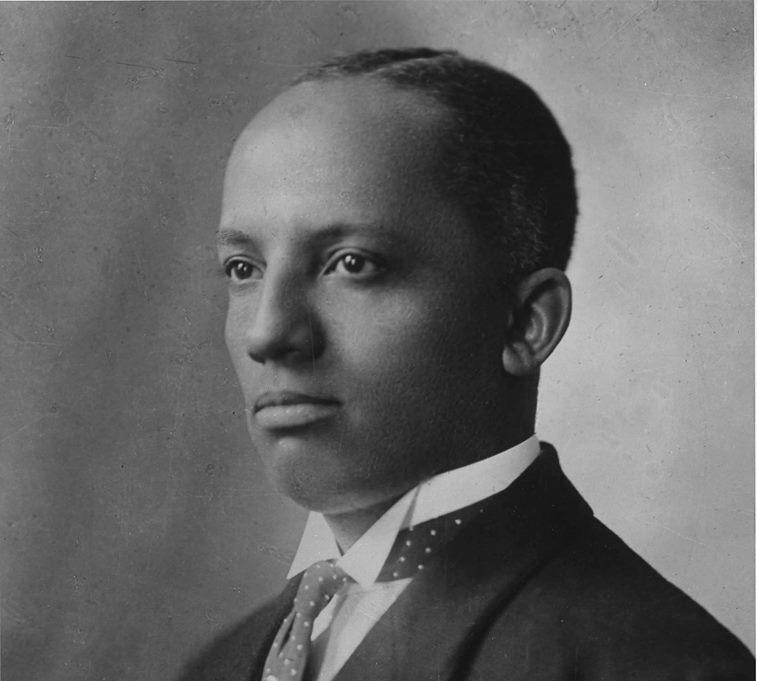

Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950), the son of parents who had been enslaved, was a pioneering scholar and public educator. He helped found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) on September 9, 1915, to create research, publication outlets, and public programs focused on Black history. Woodson believed that knowledge of the past was essential to dignity, civic participation, and survival.

Source: ASALH TV – YouTube

In 1926, Woodson and ASNLH launched Negro History Week, scheduled during the second week of February to align with celebrations of Abraham Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’s birthdays already observed in Black communities. Woodson’s stated aim was not merely to celebrate exceptional individuals but to teach the Negro in history, the collective, structural, and cultural forces that shaped Black life.

From week to month-long grassroots arc (1926 → 1976)

The shift from a week-long observance to a month-long commemoration was gradual and cumulative. Negro History Week spread through Black schools, churches, local historical societies, and city proclamations across the 1930s–1960s. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, student and community activism helped convert the week into a month. Students and Black educators at institutions such as Kent State University played a notable role in proposing and establishing campus-wide month-long programming around 1969–1970. By the mid-1970s, the month was widely observed across the country.

On February 10, 1976, President Gerald R. Ford issued the first presidential message recognizing Black History Month and urged Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans.” That statement is the first formal presidential recognition, though not a legislative act; following 1976, U.S. presidents have continued to mark the month in annual proclamations and messages.

Woodson, his scholarship, and the archival record

Woodson established scholarly infrastructure, most notably the Journal of Negro History (1916) and, later, the Negro History Bulletin, to professionalize and disseminate Black historical scholarship. His papers and correspondence are preserved in major repositories (for example, the Library of Congress holds the Carter G. Woodson papers), which remain essential primary sources for teaching and research.

A commonly used honorific, “the Father of Black History,” recognizes Woodson’s central role in institutionalizing the study and public teaching of Black history; historians also stress that this work depended on many collaborators, such as educators, civic groups, and collectors, across the Black community.

The centennial year, 2026

ASALH’s 2026 theme is “A Century of Black History Commemorations.” ASALH’s centennial programming includes national convenings, resources for educators, and partnership initiatives that aim to translate commemoration into longer-term policy and institutional change, particularly curriculum adoption, archives funding, and museum sustainability.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), which opened in 2016, is a major public partner for centennial programming: the museum provides digital toolkits and primary-source materials for teachers and curates exhibits and public events that connect Woodson’s legacy to contemporary issues.

Global reach and diasporic practices

Woodson’s idea had Pan-African instincts from the start, he and ASNLH documented Black life globally and promoted exchanges of scholarship across borders. Today, formal national observances exist in other countries (for example, Canada marks Black History Month in February; the UK and Ireland observe Black History Month in October), while many African nations and diasporic communities host festival programming, academic symposia, and curricular projects tied to the centennial. The forms and timing of observance differ by country; in Africa, centennial activity is often event-based and tied to cultural exchanges rather than a standardized national “month.”

The mandatory course in African American history will continue to be taught; history programs for adults, teens, and middle schoolers such as the ASALH (Association for the Study of African American Life and History) and Mother Bethel Church, Freedom School Academy joint program will continue; Freedom Schools will continue; programs such as the Center for Black Educator Development will continue; ASALH’s two branches, Philadelphia Heritage, the oldest and PhilaMontco will continue to EXIST and host programs; our historical and cultural sites will continue to EXIST and continue to educate and motivate; our spiritual centers will continue to EXIST and outreach; ATAC (Avenging the Ancestors Coalition) will continue to EXIST, and as attorney Michael Coard said earlier of Frederick Douglas, to AGITATE! AGITATE! AGITATE!; The BlackPrint 20 Summit program in February (6th and 7th) will happen; summer and year-round programs with history components will increase;

And this 250th celebration of America, in Philadelphia, will have focused neighborhood tours highlighting the role of African Americans and our foundational role, through the labor of men, women, and children, will happen and continue POST these celebrations! “We Ain’t No Ways Tired…” “Let us march on till victory is won!- Jacqueline Wiggins, President and CEO of Wiggins Tours & More

Source: https://scribe.org/nphf/my-story-my-block

Critiques and defenses

Black History Month has long been debated. Critics argue that concentrating Black history into a single month risks marginalizing it for the rest of the year. Defenders say annual recognition guarantees a minimum level of public memory and attention that can withstand periodic political hostility toward inclusive curricula. Both points are part of ongoing discussions about curricular reform: many educators and advocates now argue for year-round curricular integration of Black history rather than a single commemorative month.

Why the centennial matters in 2026

The 2026 centennial arrives amid renewed debates about how race and history are taught in U.S. schools. ASALH, museum leaders, and educators are using the centennial to press for three connected priorities:

- Curriculum adoption: Advocates want Black history embedded in K–12 standards year-round, not confined to a single month.

- Archives funding: Institutions are calling for expanded public and private support to preserve community archives and digitize collections (including Woodson’s papers and similar primary sources).

- Museum sustainability and restitution conversations: The centennial is a moment for museums and communities to push for expanded community partnerships, repatriation dialogues where appropriate, and sustained funding for local history organizations.

FAQ

Q1: Why is Black History Month in February?

A: Woodson chose the second week of February in 1926 to correspond with celebrations of Abraham Lincoln’s and Frederick Douglass’s birthdays in Black communities; that practice carried forward and helped fix the month’s association with Black history.

Q2: Who is the “Father of Black History”?

A: Carter G. Woodson is widely called the “Father of Black History” for founding ASNLH (ASALH) and creating the public and scholarly infrastructure that made the broader movement possible. Use the honorific with context: it recognizes his central, not solitary, leadership.

Q3: When did the “Week” become a “Month”?

A: The change was gradual: campus activism in the late 1960s and early 1970s (notably at Kent State) helped popularize the month-long observance; President Gerald R. Ford issued the first presidential recognition of Black History Month on February 10, 1976.

Q4: What is ASALH’s 2026 theme?

A: “A Century of Black History Commemorations.”

Q5: How can schools use primary sources for the centennial?

A: Teachers can draw on ASALH resources, Library of Congress collections (including Woodson’s papers), and NMAAHC digital toolkits to bring original documents, images, and artifacts into lessons. These repositories offer teacher guides and digitized materials for classroom use.

Q6: Is Black History Month celebrated outside the U.S.?

A: Yes. Canada officially recognizes Black History Month in February; the UK and Ireland observe it in October; many other countries host centennial-linked festivals and academic projects during 2026. Practices vary by country.

Centennial timeline

- 1915: ASNLH founded (later renamed ASALH).

- 1926: Carter G. Woodson launches Negro History Week (second week of February).

- 1933: Woodson publishes The Mis-Education of the Negro (seminal critique). (Primary bibliographic sources available in academic catalogs.)

- 1970 (circa): Campuses such as Kent State expand observance into a month-long program.

- 1976: First presidential recognition of Black History Month (Gerald R. Ford, Feb 10, 1976).

- 2016: NMAAHC opens in Washington, D.C., creating a major national center for public engagement with African American history.

- 2026: ASALH leads centennial programming under the theme “A Century of Black History Commemorations.”

Anand Subramanian is a freelance photographer and content writer based out of Tamil Nadu, India. Having a background in Engineering always made him curious about life on the other side of the spectrum. He leapt forward towards the Photography life and never looked back. Specializing in Documentary and Portrait photography gave him an up-close and personal view into the complexities of human beings and those experiences helped him branch out from visual to words. Today he is mentoring passionate photographers and writing about the different dimensions of the art world.