Country artist Linda Martell in the 1970s. Image Source: lindamartell.com, copyright and credit goes to original owners.

One of the most impressive parts of Beyoncé’s new album, “Cowboy Carter,” is her roster of collaborators, which includes rising country artist Shaboozey alongside country superstars Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson. But to me, the most important guest voice is the one least likely to be familiar to Beyoncé’s listeners: Linda Martell, the first commercially successful Black female country music artist.

Two tracks on “Cowboy Carter,” “Spaghetti” and “The Linda Martell Show,” include spoken word commentary from Martell. By giving Martell a platform, Beyoncé simultaneously gives credit to her predecessor while staking her place in the country music tradition.

I’ve previously written about how the categories of race and genre have long restrained country musicians. In “Spaghetti,” Martell confronts the conundrums of the genre:

“Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they? … In theory, they have a simple little definition that’s easy to understand. But in practice, well, some may feel confined.”

Confinement was the essence of Martell’s brief musical career – and it’s the exact sort of fate that Beyoncé has sought to avoid as she has moved from bubblegum pop singer to Afrofuturist oracle and country music scion. Linda Martell’s rapid ascendancy to prominence as a country musician and her equally precipitous decline offer a lesson about the challenges Black artists faced in the 1970s.

Born in South Carolina, Martell first began to sing as a child, forming a group with her sisters that performed R&B and gospel songs. After the sisters parted ways artistically, Martell often performed as a solo act. During a performance at Charleston Air Force Base in 1969, Duke Rayner, Martell’s soon-to-be agent, was in the audience. Rayner, who believed Martell could be “a female Charley Pride,” persuaded her to try her hand at country music. Having recently released the hit “All I Have to Offer You (Is Me),” Pride was proving that Black country music artists could succeed.

For a time, Martell was similarly popular.

She went to Nashville, Tennessee, to record a country version of “Color Him Father,” a soul song by The Winstons that had hit No. 7 on the Billboard Hot 100 that year. Martell’s version reached No. 22 on Billboard’s Hot Country Singles – the highest position any Black woman had reached on that chart until Beyoncé’s “Texas Hold ‘Em” debuted at No. 1 in February 2024.

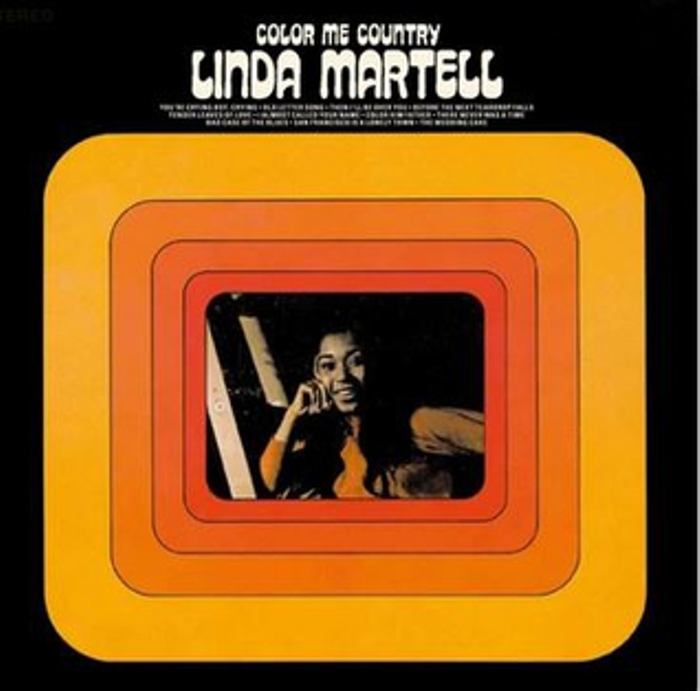

Martell followed that single with a Country Top 40 album, “Color Me Country.” One reviewer proved Rayner’s prophecy correct, opining: “Linda impresses as a female Charley Pride. She has a terrific style and a true feeling for a country lyric.”

Album cover for “Color Me Country”. Fair Use, Wikimedia Commons

Martell’s success opened doors for her in Nashville. She was invited to join a host of country artists on tour, including Waylon Jennings and Hank Snow. She also appeared on country television shows such as “Hee Haw.” Most importantly, Martell was the first Black woman to debut as a solo artist at the Grand Ole Opry, Nashville’s weekly live music program that has been the most important venue for country artists since the late 1920s. Over the next five years, she made 11 subsequent appearances on the stage of “the Mother Church of country music.” More than once, Martell sang her songs to audiences that shouted back racial slurs. Reflecting on the experiences in 2021, she noted, “You’re trying to entertain and be called a name very, very loudly in a club or arena and try to get through the song without crying.”

For all the pain and anger she felt, Martell didn’t dare react to the taunts, though she often wondered why people couldn’t “just sit there and enjoy the music.” Martell also faced thinly veiled racism from the people who were supposed to be promoting her career.

Producer Shelby Singleton, who signed Martell, didn’t release “Color Me Country” on his SSI label, opting instead to record her on a subsidiary label, Plantation Records.

While he promoted Martell for a time, when one of his white artists, Jeanne C. Riley, recorded the smash hit “Harper Valley PTA,” Singleton threw all of his energy and attention behind Riley.

With her record company promoting what essentially amounted to a one-hit wonder at her expense, Martell tried to switch labels.

Singleton responded by essentially blackballing her in Nashville, ensuring no other label would sign her. Martell all but disappeared from the public eye by 1974.

She tried returning to R&B, but her career ultimately fizzled.

In the 2005 documentary “Waiting in the Wings,” Martell offers words of advice for any who would follow in her footsteps: “A woman of color if you go into country music – if the record stations don’t play you, you are not going anywhere. Brace yourself. But don’t give up.”

Martell’s industry exile resonates with one element of “Cowboy Carter,” in particular.

Beyoncé has said that she made the album, in part, as a response to a time when she “felt excluded.” She has never said when, exactly, that time was, but I think she could well be alluding to her performance of “Daddy Lessons” with the Chicks at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards. Members of the audience were cool to her presence, at best; one country music mainstay, Alan Jackson, got up from the front row and walked out in the middle of the song.

With “Cowboy Carter,” Beyoncé has triumphantly returned, kicking the doors open and marching through them with Martell proudly by her side, giving the 82-year-old country star the recognition that has long eluded her.

Beyoncé seems to know that no cultural box can contain her, and I see “Cowboy Carter” as a revolutionary album because Beyoncé is paving the way for more musicians to take creative risks, refuse to be pigeonholed, and break the artificial boundaries of genre.