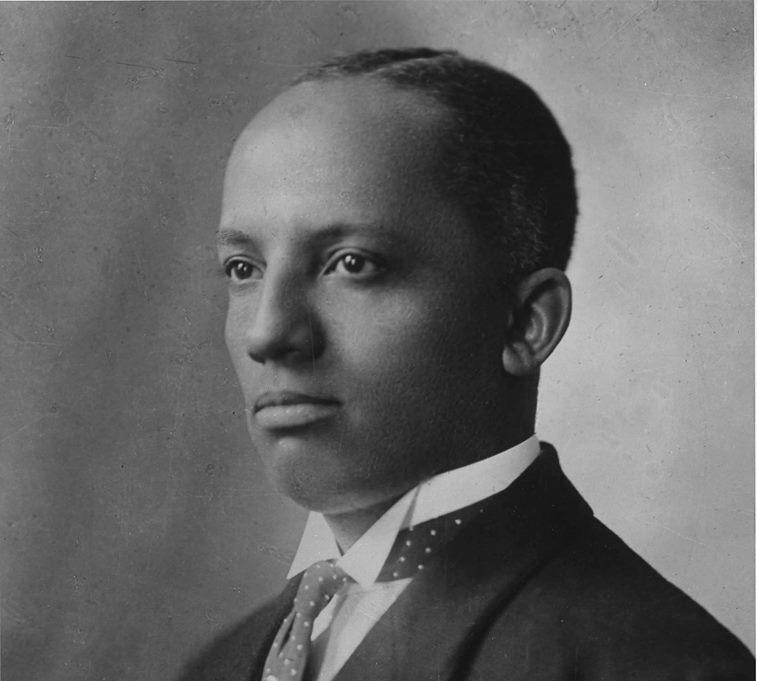

Unknown, book in which the image is published in was edited by W. N. Hartshorn and George W. Penniman., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Long before formal nursing schools or medical licenses, Black women brought life into the world under the shadow of slavery. Enslaved midwives labored in cramped cabins, relying on generations of oral knowledge to care for mothers and infants alike. Among them, Elizabeth “Mumbet” Freeman, later known simply as Elizabeth Freeman, stands out not only for her courageous suit for freedom but also for her work as a midwife and herbalist in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. After winning her freedom in 1781, Freeman continued to serve her community, delivering babies and sharing herbal remedies well into her eighties, and became the only non-Sedgwick interred in the family plot that honored her service.

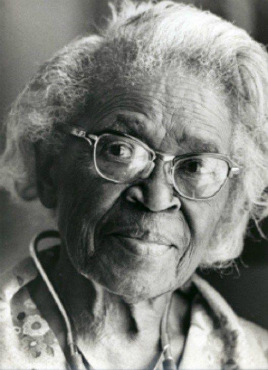

Elizabeth Freeman. Source: Wikipedia

While Freeman’s name survives in court records and family lore, countless “unknown” midwives left fewer traces in the archival record. Their contributions emerge in plantation narratives, like an 1830s account from South Carolina describing an enslaved woman who delivered dozens of babies in a single season, stitching wounds and calming frightened mothers with her steady hands. These hidden histories remind us that, even under bondage, Black women sustained life and laid the groundwork for future generations of caregivers.

Civil War & Reconstruction Era (1861–1877)

The Civil War upended American medicine—and offered unprecedented opportunities for Black practitioners. In Union hospitals, Black nurses and caregivers tended to wounded soldiers at the front and behind the lines. After the war, the Freedmen’s Bureau’s Medical Division established hospitals and clinics to serve formerly enslaved people, recruiting Black women like Rebecca Lee Crumpler, America’s first Black female physician, to staff them. Dr. Crumpler earned her M.D. in 1864 and, in 1865, traveled to Richmond, Virginia, to provide medical care to freedmen and freedwomen under the Bureau’s auspices. Her 1883 book, A Book of Medical Discourses in Two Parts, remains one of the earliest medical texts authored by an African American.

In Washington, D.C., Freedmen’s Hospital opened in 1862 under the Freedmen’s Bureau’s Medical Division, offering Black patients dignified care and training the first generation of Black nurses. Staffed by graduates of the Freedmen’s Hospital School of Nursing and Howard University, these institutions provided critical services during the 1918 influenza pandemic, when Black nurses braved segregation and scarce resources to save lives.

Freedmen’s Hospital . Source: Duke University

Segregation & the Jim Crow Hospitals (1877–1945)

As Reconstruction gave way to Jim Crow, Black doctors and nurses found themselves barred from white institutions. In response, they built their medical schools and hospitals. Meharry Medical College, founded in 1876 in Nashville as the Medical Department of Central Tennessee College, became the first medical school in the South dedicated to African Americans. By 1896, half of all formally trained Black physicians in the South had graduated from Meharry’s halls.

In Chicago, Dr. Daniel Hale Williams opened Provident Hospital and Training School for Nurses in 1891, the nation’s first non-segregated hospital, staffed and led by Black practitioners but open to all races. There, in 1893, Williams performed one of the first successful pericardial sac repairs, often hailed as the first open-heart surgery in the United States. His bold operation not only saved patient James Cornish but also challenged prevailing myths about Black physicians’ competence.

Maude E. Callen. Source: Wikipedia

Meanwhile, Black midwives like Maude E. Callen traversed the rural South by horseback, delivering hundreds of babies and training local women as caregivers. Based in Pineville, South Carolina, Callen served an area of over 400 square miles, often working long hours without pay and teaching midwifery to ensure a lasting legacy in her community.

Civil Rights to Modern Day (1946–Present)

The post-war era saw both progress and backlash. In 1946, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses dissolved into the American Nurses Association, marking formal integration but also the erasure of a Black-led professional body. In 1971, frustrated by ongoing exclusion, nearly 200 Black nurses founded the National Black Nurses Association (NBNA) in Cleveland, Ohio, championing professional development and addressing health disparities in Black communities.

Today’s Black healthcare leaders stand on this legacy of advocacy. Dr. Kizzmekia Shanta Corbett, known affectionately as “Kizzy”, led the NIH Vaccine Research Center’s Coronavirus Vaccines & Immunopathogenesis Team, playing a pivotal role in developing the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine and earning a spot on the Time 100 Next list in 2021. Now an assistant professor at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, she mentors emerging scientists and advocates for vaccine equity, ensuring that communities of color gain access to life-saving innovations.

Enduring Challenges & Future Horizons

Despite these milestones, deep disparities persist. Black Americans face higher rates of maternal mortality, chronic disease, and limited access to care. Organizations like the National Medical Association (founded in 1895) continue to lobby for policy changes, while NBNA chapters nationwide run health fairs, blood-pressure screenings, and mentorship programs to cultivate the next generation of practitioners.

Innovations in telehealth, community-based research, and culturally competent care offer promising pathways. Scholarship programs, such as the United Negro College Fund’s health professions awards and initiatives like the Association of American Medical Colleges’ Holistic Review Project aim to diversify the workforce. Readers are encouraged to explore resources at:

- National Black Nurses Association: https://nbna.org

- National Medical Association: https://www.nmanet.org

- Corbett Lab (Harvard Chan): https://hsph.harvard.edu/research/corbett-lab

To support Black healthcare workers today, consider mentoring a student, donating to scholarship funds, or volunteering with community health organizations. By investing in their education and well-being, we honor the “healing hands” that have nurtured this nation across centuries and forge a future where quality care is truly for all.

Anand Subramanian is a freelance photographer and content writer based out of Tamil Nadu, India. Having a background in Engineering always made him curious about life on the other side of the spectrum. He leapt forward towards the Photography life and never looked back. Specializing in Documentary and Portrait photography gave him an up-close and personal view into the complexities of human beings and those experiences helped him branch out from visual to words. Today he is mentoring passionate photographers and writing about the different dimensions of the art world.