English: “Copyright 1943 Twentieth Century–Fox Film Corp.”, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

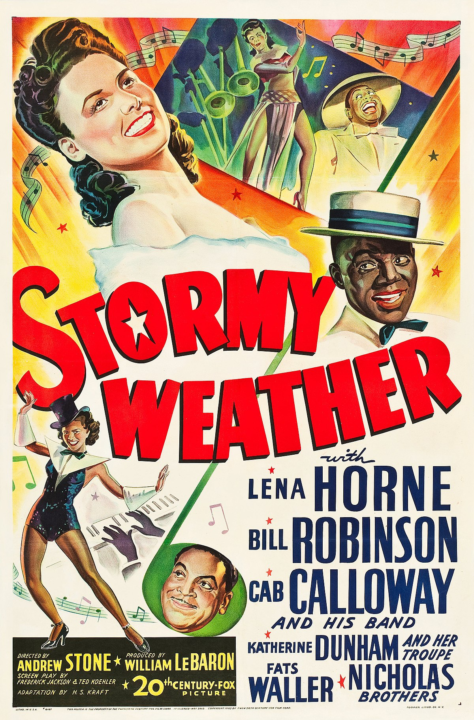

The 1943 film Stormy Weather sits at a unique intersection in cinematic history, embodying Hollywood’s WWII-era discovery of new audiences and the complex relationship between African-American culture and performance. Hollywood’s traditional white movie-going audience was partially diverted by the war abroad, so the industry recognized an opportunity to tap into African-American viewers. This demographic had long existed but seldom been directly marketed to meaningfully. This “sudden-onset awareness” wasn’t coincidental; it was strategic, as the industry sought to expand its reach and maintain box office success. But this awakening was not purely a progressive shift in representation—Hollywood mined long-standing cultural stereotypes and historical associations between African Americans and performative arts, packaging them into a palatable product for white audiences as much as for Black ones.

Source: Stormy Weather (1943 film) – Wikipedia

One of the most prominent symbols of this approach is Stormy Weather. The film is a classic Hollywood musical rooted in the Busby Berkeley “backstage” tradition of putting on a show. However, in this instance, the cast was predominantly Black, and the presentation both drew upon and departed from prior tropes about African-American physicality, expressiveness, and rhythm. For white audiences, who had long consumed racialized performances on stage and screen, Stormy Weather was an opportunity to engage with Black “theatricality”—a kind of physical externalization of culture that both fascinated and reassured white viewers.

However, this film also embodies the conflicted relationship between the necessity of Black performance and the broader system that essentializes African Americans as natural entertainers. The performance and physicality celebrated in Stormy Weather carry the weight of centuries-old systems that historically valued Black bodies for their labor and physicality, not their intellect or individuality. For African Americans, performance has long been both a livelihood and a paradox: it provides economic value, yet it frequently reinforces limiting perceptions. African-American artists were encouraged to channel their expressiveness in ways that entertained white audiences while often overlooking or suppressing the full spectrum of Black creativity and intellectuality.

Yet, African-American culture itself holds deep connections to performance and physical expressiveness, stretching back to African animism and the communal, ritual dances of enslaved people in the American South. Dance and performance were more than entertainment—they were acts of defiance, mechanisms for releasing pent-up frustration, and subtle rejections of subservience. By embracing physicality as a form of expression and resistance, enslaved people redefined the idea of movement, not just as a labor function but as an assertion of autonomy and creativity. In this way, films like Stormy Weather capture the dual nature of Black performance as empowerment and constraint, reflecting a cultural lineage that values bodily expression as a form of resilience.

Source: Stormy Weather. 1943. Directed by Andrew L. Stone | MoMA

The film’s plot, centering on Bill Robinson’s character and his romance with Lena Horne’s Selina Rogers, is a microcosm of these broader cultural tensions. Their story explores the delicate balance between personal ambition and societal expectations, encapsulated by the film’s climax and denouement. Robinson and Horne’s characters are irresistibly drawn to the stage, a space where they can freely express their talents and charisma. Cab Calloway joins them as another prominent figure in the film, and his performance style, already flamboyant and boundary-pushing in real life, is similarly amplified. The film’s final scenes—where Robinson and Calloway dazzle audiences with boundary-breaking dance—are exhilarating, representing a space where traditional dance forms are stretched to new expressive limits.

But Stormy Weather’s ideological underpinnings are layered with contradictions. On the one hand, it showcases Black talent in a way that celebrates artistry and energy, allowing the central characters to shine in roles that were progressive by Hollywood standards at the time. On the other hand, the film’s narrative arc ultimately reins in this freedom. The framing device presents Robinson and Horne as successful entertainers who, in the end, “settle down,” symbolizing Hollywood’s endorsement of assimilation into the American Dream. The film implicitly suggests that the path to success and respectability lies in conforming to ideals of stability and domesticity.

The broader implication is that transient or “non-settled” Black life, symbolized by Horne’s character’s love for a nomadic burlesque troupe, was viewed as a phase, a deviation from the norm. This message dovetailed with broader American narratives in the post-war era, where the suburban ideal and the nuclear family became hallmarks of the “proper” American life. Horne’s character’s journey, then, mirrors the film’s implicit endorsement of settling down, implying that a stable home life is the ultimate aspiration, even for those rooted in a culture of performance and movement. In so doing, Stormy Weather ultimately reinforces the value of assimilation over the spontaneity and flexibility associated with the African-American experience.

Hollywood in the 1940s, with its simultaneous flirtation with inclusivity and conservative ideals, produced films like Stormy Weather as microcosms of the American cultural dilemma. The movie celebrated aspects of Black culture but ultimately sought to confine them within acceptable boundaries. While Stormy Weather allows viewers to revel in celebrating Black performance and resilience, it’s equally eager to show the rewards of assimilation into the mainstream American Dream. African Americans, the film suggests, had finally “made it” by showcasing not only their talents but also their ability to conform to the dominant narrative of home and family.

In Stormy Weather, we witness both the liberation and the limitations of African-American performance, underscoring Hollywood’s complex and often contradictory relationship with Black culture. The film is as much a tribute to Black artistry as it reminds of the constraints imposed upon it—a cinematic artifact from when Hollywood needed new faces to sell, yet wasn’t ready to fully embrace their narratives. The result is a richly expressive yet tantalizingly restrained film, a blend of hope and compromise, and an iconic example of Hollywood’s ongoing negotiation with American identity and race.

Anand Subramanian is a freelance photographer and content writer based out of Tamil Nadu, India. Having a background in Engineering always made him curious about life on the other side of the spectrum. He leapt forward towards the Photography life and never looked back. Specializing in Documentary and Portrait photography gave him an up-close and personal view into the complexities of human beings and those experiences helped him branch out from visual to words. Today he is mentoring passionate photographers and writing about the different dimensions of the art world.