Nowruz eve among Mazanderani people, photo from Wikimedia Commons

As the world slowly bids winter goodbye and nature begins to blossom with the arrival of springtime, a vibrant and ancient celebration blooms across the globe: Nowruz, the Persian New Year.

When we think of New Year’s celebrations, we often think of the ball drop at Times Square, fireworks, and countdowns. But across the world, some other people welcome the new year in their own unique ways, different from what we know. One such celebration that has been gaining global recognition is Nowruz.

Nowruz isn’t just any New Year celebration, it is a deeply cultural, historical, and spiritual event observed by millions of people across the world. From Persia to Central Asia, the Middle East, and even parts of Europe, this festival, which goes back over 3,000 years, carries profound meaning for those who observe it. Rooted in Persian culture, Nowruz is a time of celebration, reflection, renewal, family gatherings, and age-old rituals that symbolize hope for the year ahead.

Unlike the Gregorian New Year on January 1st, which is based on the solar calendar, Nowruz is celebrated on the day of the astronomical vernal equinox—the moment when day and night are equal in length, which usually takes place between the 19th and 21st of March.

Nowruz, which translates to “new day,” was originally linked to the Zoroastrian faith, which preceded both Christianity and Islam. Exactly when Nowruz began as a festival is unclear, but many believe its origins can be traced back to the ancient Persian empire and the Zoroastrian calendar, where it marked one of the holiest days of the year. Originally a sacred time to celebrate the rebirth of nature, Nowruz has evolved with time into a secular festival embraced by numerous ethnolinguistic and cultural communities.

It is celebrated by various ethnic groups across Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Balkans, including Iranian, Pakistani, Afghan, Turkish, Tajik, and Kurdish communities. Persians, Parsees, Kurds, Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Tajiks, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, and many more cultures also celebrate this festival with different traditions.

Nowruz Gaining Global Recognition

In recent years, Nowruz has stepped into the global spotlight, catching the attention of people from all walks of life, including Black travelers and those who love culture and tradition. African Americans can relate to this festival as it shares similarities with Black celebrations like Kwanzaa.

This festival, which holds profound meaning for Iranians and many other communities globally, has long been seen as a symbolic turning point when winter’s darkness and cold give way to spring’s light and warmth.

In major cities like Los Angeles, Toronto, London, and New York, Nowruz festivals attract thousands. It usually features Persian music, dance, and food.

The Nowruz celebration is part of UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Recognizing its cultural significance and universal appeal, the United Nations General Assembly of 2010 designated March 21st as the International Day of Nowruz.

“In these times of great challenge, Nowruz promotes dialogue, good neighborliness, and reconciliation,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres stated.

How do People Celebrate Nowruz?

Just like Christmas, Eid, and many other celebrations, Nowruz is celebrated with family and friends and includes parties with lots of special food. In many regions, Nowruz is characterized by nearly two weeks of celebration.

The arrival of Nowruz is announced by street singers, known as Haji Firooz, who wear colorful outfits and play the tambourine.

Though the celebrations vary from country to country, some common traditions are shared, which include symbolic preparations with fire and water and ritual dances that sometimes involve jumping over fires.

Before the start of Nowruz, traditional spring cleaning takes place in the houses, symbolizing home renewal and the removal of negative energies.

The Haft-Seen table:

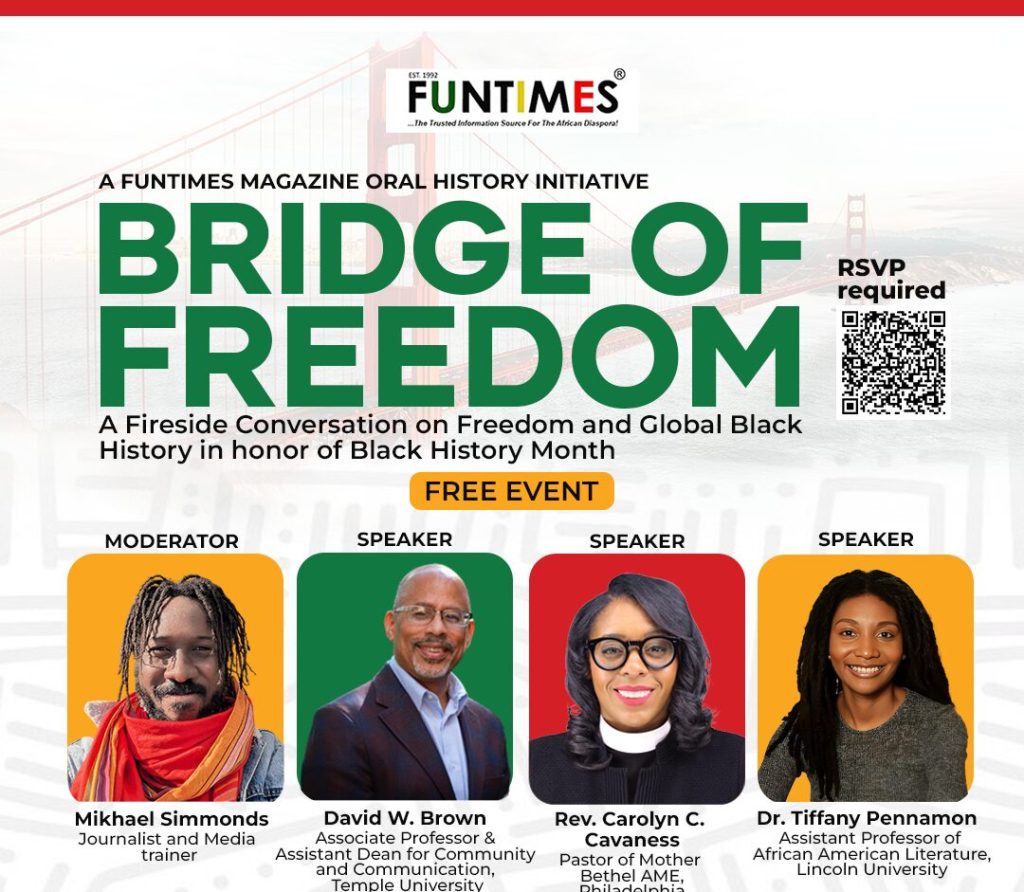

One of Nowruz’s most iconic traditions is the Haft-Seen, a symbolic table setting, especially popular in Iran. This table is artfully arranged with seven items, each beginning with the Persian letter “S” representing different aspects of life and blessings for the upcoming year. These can include:

- Sirkeh (vinegar): Represents age and patience that often comes with aging

- Sikkeh (coin): For wealth and prosperity

- Seer (garlic): For good health

- Seeb (apples): For health and natural beauty

- Sabzeh (wheat): For rebirth, renewal, and good fortune

- Samanu (wheat pudding): A sweet dessert for wealth, fertility, and the sweetness of life

- Sumac (berries): For the sunrise and the celebration of a new day.

The table might also include a mirror to symbolically reflect the past year, painted eggs to represent fertility, a goldfish to represent new life, and candles to show light and happiness.

Fire rituals: Fire plays a central role in Nowruz celebrations. In many regions, people take part in fire rituals such as Chaharshanbe Suri in Iran. Jumping over bonfires is a symbolic act meant to purify and energize, casting away the remnants of winter and inviting the warmth and vitality of spring into one’s life.

Variety of food:

Another important part of the festival is the food. A variety of food dishes are prepared with family and friends, fostering a sense of togetherness. Some serve “ash-e reshteh” or noodle soup, which is believed to symbolize the “many possibilities in one’s life”. In Central Asia, the sweet wheat pudding known as sumalak is cooked slowly over many hours, symbolizing the slow but sure arrival of spring and new beginnings.

Special sweets, including baklava and sugar-coated almonds, are also believed to bring good fortune and are shared during the celebration. Other dishes include fish served with special rice with green herbs and spices, symbolizing nature in spring.

Persians (Iranians) in Holland Celebrating Sizdeh-Bedar, April 2011, Photo by Pejman Akbarzadeh / Persian Dutch Network

Sizdeh Bedar:

The festivities last for 13 days after the New Year, culminating in Sizdeh Bedar, the 13th and final day of Nowruz. On this day, many leave their houses to enjoy nature and picnic outdoors. The number 13 is often considered unlucky in Persian culture, so staying indoors on the 13th day of Nowruz is believed to bring bad luck.

Just as Black culture celebrates resilience and community, Nowruz is a testament to the power of cultural heritage and community. Whether celebrated in a traditional Persian home, a modern apartment in Philadelphia, or a festival in London, Nowruz is an invitation to honor life’s cycles and embrace the new with open arms.