Image: A significant collection of traditional African art has had a home in Canada for almost 100 years. (Qanita Lilla), Author provided via The Conversation

A significant collection of traditional African art has had a home in Canada for almost a hundred years.

At Agnes Etherington Art Centre, we are working on new, more hospitable practices of care for this collection. This means that we are attentive to the unmet needs of the collection and are taking responsibility for responding to these in ways that encourage community access and inclusion.

We are located at Queen’s University, in Kingston, Ont., on the territories of the Anishinaabek, Haudenosaunee, and Huron-Wendat, in a city where over 7,000 people identify as First Nations, Inuit, or Métis.

The African art collection, named after donors Justin and Elisabeth Lang consists of approximately 600 three-dimensional pieces that originate from 19 West African countries.

This collection is part of a cluster of similar collections in North America that made their way via European art markets. In 1938, Elisabeth Lang (nee Von Taussig), fleeing from Nazi-occupied Vienna, started the collection with a Baule figure from Ivory Coast that she purchased in an Amsterdam junk shop.

The European market in African art had boomed in the 1920s and 1930s. European enthusiasm for African art was partly due to its influence on modernist artists, such as Picasso, Cézanne, and Gauguin.

From the early 1900s, cultural belongings from West Africa were placed on the art market directly from European, mainly French, colonies. Buyers and sellers were colonial officials, missionaries, or in the military. This commercial network remained intact as the appreciation of African art shifted dramatically from an ethnographic bias where African objects were studied as materials of a specific people, to becoming African “art” for aesthetic contemplation.

Both these frameworks for studying African material had a colonial bias. As scientific specimens, objects from Africa were often used as evidence of racial and cultural differences. The term “primitive” art demonstrates this racism.

As art, these objects were used to qualify Africa as mysterious and incomprehensible to the Western mind. The establishment of an African art market, therefore, had direct ties to European colonial projects and imperial commercial networks that reinforced colonial violence.

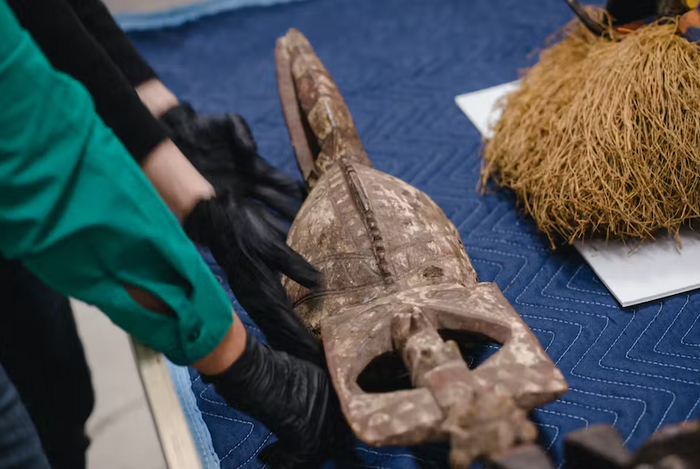

Agnes staff are seen positioning African pieces. (Tim Forbes), Author provided via The Conversation

The Lang family donated the collection to Agnes in 1984. At the time, it was the largest collection of African art at a Canadian university. As a body, the collection has had at least four lives: one within Africa as an active part of everyday life, another in Europe as part of a thriving art market, in Canada as a private art collection, and now as a museum holding on a university campus.

But our records of these lives are sparse. We know very little about the contexts in which the individual pieces were produced, bought, and sold in Africa, from as far south as Angola to as far north as Mauritania.

Instead, museum records and databases focus on other things: the place of origin, material makeup, and physical size. These kinds of records were made for institutions, not communities.

Decolonising Cultural Spaces: The Living Cultures Project, is an initiative with a short film at its heart about uniting Indigenous communities across borders, to celebrate and protect their cultures.

In this film, Samwel Nangiria, the Maasai community leader, notes:

“You are not holding artifacts, you are holding communities … museums need to be a place of people, not a place of artifacts. When we see these objects we see our parents, we see our ancestors.”

Read also:

As curator of the Lang collection, I am rethinking its future role. How do we adjust our practices to respond to a colonial past and the gaps in our understanding? Considering voices like Nangiria’s in restitution debates, I believe that while the collection resides with us, we have the responsibility to respond to new questions:

- What does it mean to think of the collection as living, and of needing to be concerning communities?

- How does a museum meet these evolving needs, and practice better care?

- How do we respond to a complex history proactively, highlight absences and enable alternatives?

Exhibition view of ‘With Opened Mouths,’ 2022. (Tim Forbes), Author provided via The Conversation

Agnes’s 2022 exhibition With Opened Mouths drew on sculptural elements from contemporary art and incorporated the work of Nigerian Canadian artist Oluseye Ogunlesi.

This exhibition was conceived under the pandemic lockdown in Cape Town. I was confronting isolation, impending economic migration to Canada, and the start of curatorial work at Agnes and Queen’s University. I felt compelled to find new ways to enliven a collection that inhabited an awkward silence in the museum.

Then the dance craze, “Jerusamela,” by Master KG and Nomcebo, became a global phenomenon. Mobilizing the world, it presented another view of Africa: action, aliveness, and contemporaneity.

For the Agnes exhibit With Opened Mouths, we discarded the glass display cases often used in museums and instead used labeling that echoed contemporary African signage. To open spaces outside the museum, a podcast ran alongside the exhibition and currently continues into a second season. With Opened Mouths: The Podcast is a digital safe space where I interview racialized creatives to discuss their practice.

The podcast not only reflects on the journeys of artists but also the crucial value of artistic communities.

On July 15, the Lang Collection makes its next journey. The collection will move to a temporary home on campus in preparation for renovations at Agnes. These renovations are not only about expanding Agnes’s space but also about decolonizing Agnes’s curatorial practices.

The move of the African collection out of the vault is momentous. Although portions of the collection have been on display before, this is the first time the entire collection has been brought above ground to once again be part of the living world.

To honor the liveliness of beings and history both seen and unseen, on July 15 we are holding a ceremonial procession, Vulindlela! Out the Gates, named after South African music icon Brenda Fassie’s post-apartheid hit music single.

Agnes staff and community members will celebrate with music, poetry, and dance, and we will launch the poetry bundle of eleven metal tongues written by award-winning poet Otoniya J. Okot Bitek. The project emerged after Bitek’s first visit to the vaults.

Bitek’s poetry evokes a deep sense of being in the collection’s presence, of the uneasy fit of written descriptions in collection databases with the quivering reality before us, the inadequacies of language, and suppressed stories. Vulindlela! will be a moment of hope, welcome, and care. It marks a renewed commitment to reconsider the living significance of these belongings.

In essence, these curatorial practices seek to acknowledge the African communities and artists who have, unknowingly, built up the collection at Agnes.

The hearts, hands, and minds of those who remain unnamed need their labor celebrated, and their voices heard.