Town Hall Kingston, Ontario. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Nineteenth century Black history is missing from the mainstream story of Kingston, Ont., but traces of this history in the city’s archives show that it undoubtedly had a Black presence.

Research undertaken for a curatorial collaboration at Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s University is attempting to fill this gap.

Kingston is a historical city. Located on Lake Ontario at the apex of the St. Lawrence and Cataraqui Rivers, it was Canada’s first legislative capital, and was always an important place for Indigenous gathering.

Today, the city acknowledges it sits on the traditional homeland of the Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, the Huron-Wendat and is home to a “growing urban population of over 7,000 residents who identify as First Nations, Inuit or Métis.”

At Agnes, Emelie Chhangur, director and curator, Sebastian De Line, associate curator care and relations, and myself, associate curator, Arts of Africa, are piecing together early Black histories in a place that has long been defined by histories of Canadian whiteness.

Agnes has an art collection of over 17,000 pieces, some of which have complex colonial histories. Today, the museum finds itself at a watershed moment of having to reckon with its past as well as Kingston’s.

At Agnes, Chhangur considers the transformative potential of the art museum, where new collaborative curatorial methods can counteract past colonial practices. These practices include extracting material and knowledge in a colonial way and overlooking people who do not conform to white dominance in society.

Along with my colleagues at Agnes, I see this work as part of a broader historical reckoning already being undertaken by dynamic groups like OPIRG Kingston and Keep Up With Kingston. OPIRG has a mandate of pursuing social justice work critical to the city, seen in The People’s History Project.

Networks like Keep Up With Kingston engage Black lived experience in the city by spreading news on food, cultural and literary events by Black-run businesses.

As we at Agnes engage with people who are revitalizing Kingston, the city has become a place where new opportunities for dialogue are rising.

Zina Saro-Wiwa. Source: Instagram

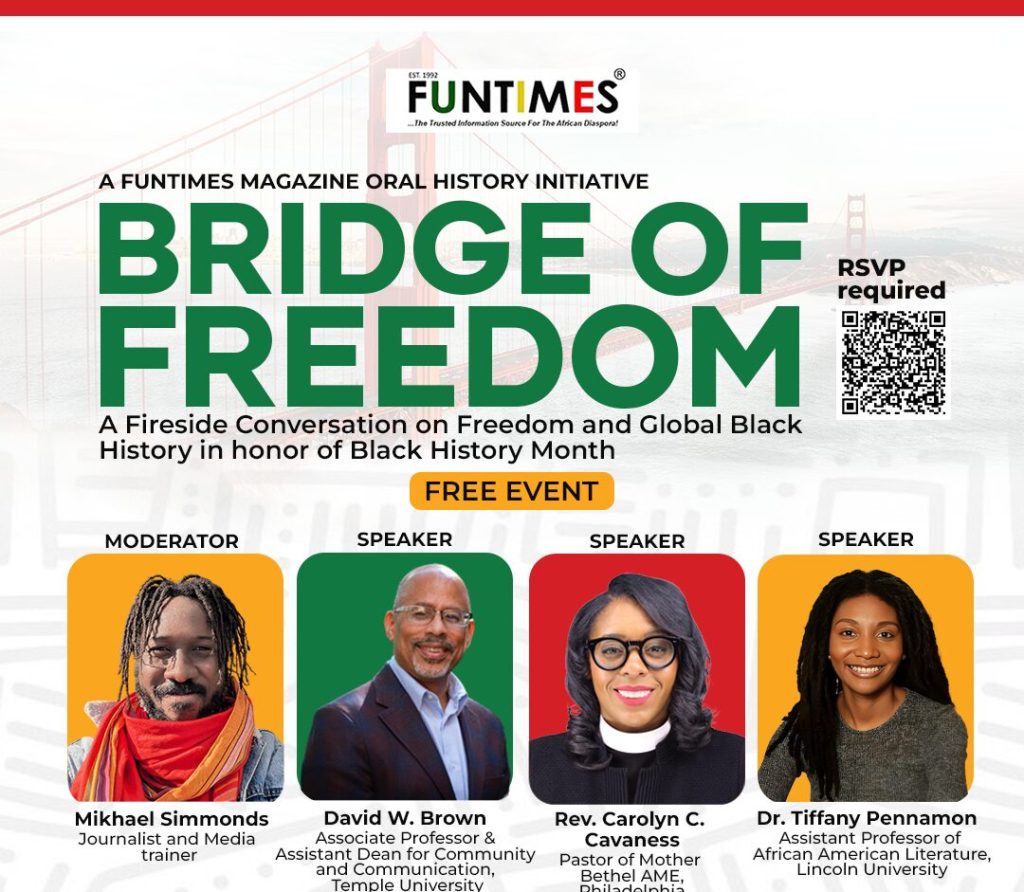

Our journey into Black history was precipitated by the artistic work of British-Nigerian artist Zina Saro-Wiwa, who will visit Kingston in March 2023. Saro-Wiwa’s “Illicit Gin Institute,” is an artistic project which takes up the theme of palm wine spirit (also known as “illicit gin”) to expose deeper and surprising narratives about her place of origin, the Niger Delta.

Her curated assemblies are public gatherings that are responsive to the places they are situated in. In this way Saro-Wiwa uses gin as a lens through which to undertake multiple artistic investigations.

In preparation for the Kingston assembly, curators and the artist are thinking about Black histories as illicit to a city imagined as white. We think of the fermentation process as tied to the land, but we also consider how distillation might be a useful metaphor to rethink collaborative history recovery processes.

The gin distillation process involves three distinct stages known as a head, heart and tail. The head is from the beginning of the run and contains a high percentage of low boiling point alcohols, the heart is the desirable middle and the tail has the highest percentage of oil — and is discarded.

White supremacist historical narratives have discarded essential and rich elements. Our collaborative curatorial process is about documenting history beginning with cherishing every little relational trace.

Piecing together Kingston’s Black history has happened mostly through primary archival sources: newspaper articles on microfilm, adverts for businesses, legal petitions, diary entries, old photographs and city maps.

Secondary sources are from online blogs and websites. Stones Kingston is an archival website, from Queen’s University, that contains a thread of local 19th-century Black history.

Through this portal we found the names of prominent Black business owners in the city: William Johnson, James and Marie Elder and George Mink.

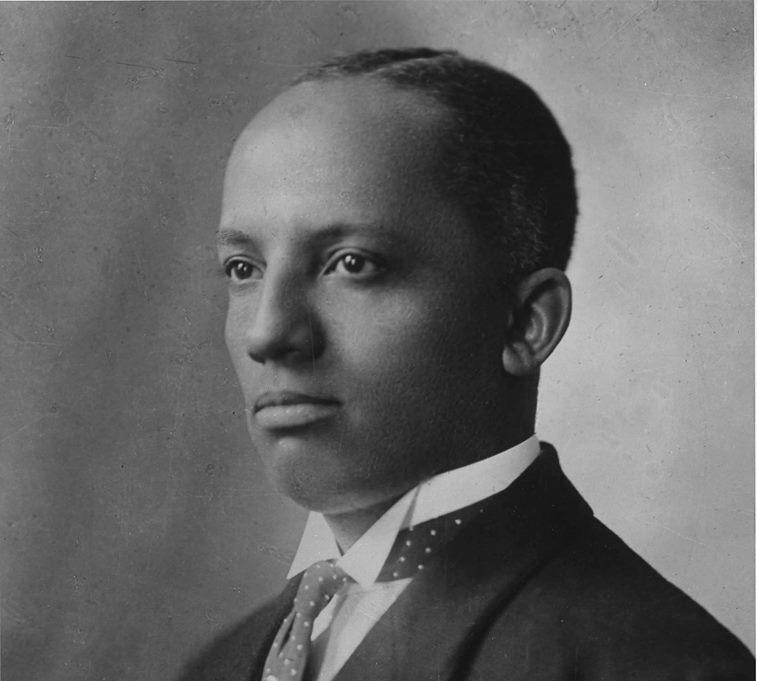

George Mink was a well-known figure in early Kingston. He was a son of enslaved Mink senior who arrived in the city as the “property” of John Herkimer (also known as Johan Jost Herkimer) after the American Revolution.

George Mink owned hotels and livery stables and was also awarded the contract for the stage coach and mail routes from Kingston to Toronto and across Wolfe Island. He was popular among his peers who nominated him as Alderman in 1850, a position he did not take up.

Many parts of Mink’s story remain untold and the sources are thin. It is unclear what happened to George Mink at the end of his life, because following the establishment of the railroad he lost his coach licenses and died in poverty.

According to a 1952 book Kingston, the King’s Town, by James A. Roy, who retired from the Queen’s University literature department in 1950, Mink was laid to rest in an unmarked grave and his body was exhumed by Queen’s medical students. The author relays this as fact, but there are no reliable references to support this.

It is sad that Roy’s mention of George Mink is the only time this prominent Kingston resident appears in a monograph. A more significant piece of writing is a 1998 article in the journal Historic Kingstonwritten by Rick Neilson and published by the Kingston Historical Society. This article focuses on Mink’s businesses in Kingston but offers no clarity on the end of his life.

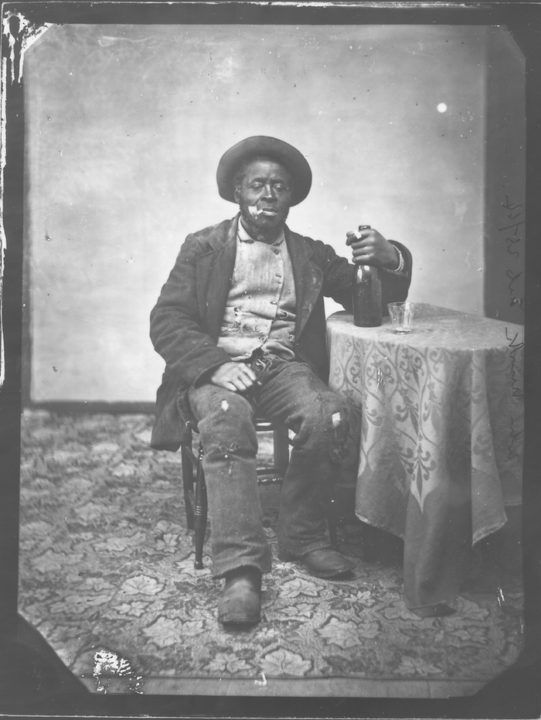

There are no photographs of George Mink, but we have found an 1864 portrait of his nephew, Tobias Mink.

Tobias Mink, Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

In a photographic studio he sits in a chair holding a bottle of alcohol, wearing a hat and smoking a pipe. His torn clothes speak of a working man. Records state he was a “cartman” and that he did manual labour around town.

We know that Tobias lived at Minks Bridge in Napanee, 48 kilometres from Kingston — a bridge named after his family — and that he was photographed in Stephen Manson Benson’s photographic studio. In a collection of 385 glass-plate negatives depicting the townspeople, Tobias Mink was the only Black person photographed.

This curatorial project aims to make this quiet Kingston history lively and visible.

As a curatorial team collaborating with artist Zina Saro-Wiwa, we seek to find networks of solidarity that were not afforded to us in the past. But we also aim to expose the challenges inherent to history writing so long forgotten.

Together we are trying to bring forth and distil local Kingston histories that have been submerged while thinking of new ways of assembling this rich history.