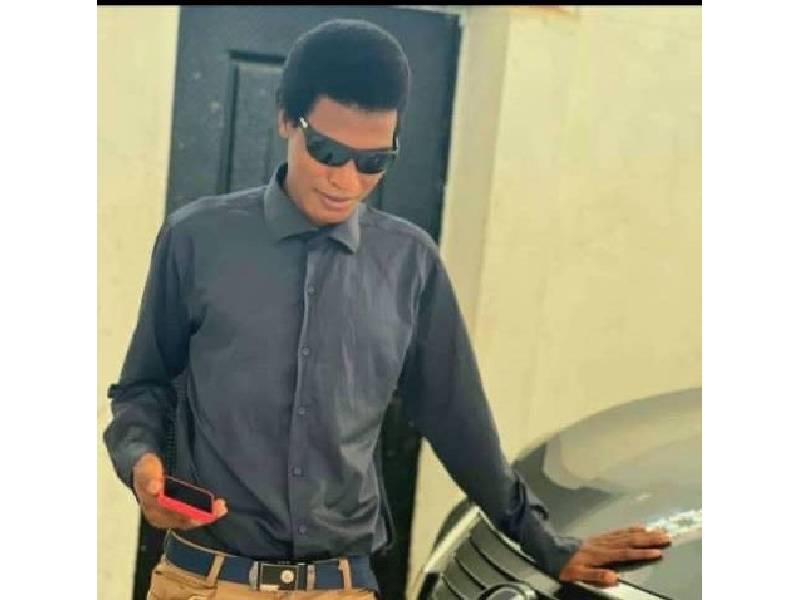

In a classroom of 35 students, Alieu Jallow stands confidently, teaching English Language with clarity, warmth, and authority. His voice moves across the room, explaining, questioning, and guiding. To his students, he is “Sir.” A teacher, mentor, and disciplinarian when needed.

Alieu’s journey to this classroom was never simple. At the age of four, Alieu lost his sight to retinoblastoma. A rare and aggressive cancer that attacks the retina of the eyes. What began as an illness soon became a life-altering turning point. Doctors were clear; surgery was necessary to stop the spread of the cancer, but it would cost him his vision. His parents struggled with the weight of that decision. It was his grandfather who eventually signed the consent form, choosing life over sight.

That decision saved Alieu’s life, but it placed him on a path filled with barriers few children should have to navigate.

Growing Up Blind in a System Not Designed for Inclusion

Alieu began his education at the only school for the blind in The Gambia, where he studied from Grade 1 to Grade 4. There, accessibility was possible, Braille books were available, and organizations like the Gambia Organization of the Blind helped ensure learning materials were provided, but this changed when the government introduced a policy to integrate students with disabilities into mainstream schools.

Transitioning from a fully blind school into a mainstream environment was one of the most difficult periods of his life. Suddenly, Alieu was the only blind student in a school full of sighted peers. He had to relearn how to exist socially and academically in a space that was not prepared for him.

Holidays were lonely, making friends felt impossible, the school environment was overwhelming, and the challenges became so intense that he no longer wanted to go to school. Yet, slowly, he adapted. He learned the rhythms of mainstream education, he made friends, and learning alongside sighted students became normal, not because the system adjusted, but because Alieu endured.

One of the greatest struggles Alieu faced was access to learning materials. In the blind school, books were embossed in Braille. In mainstream schools, they disappeared. There were no Braille textbooks, no accessible learning materials, no systematic support. To keep up, Alieu recorded his teachers’ lessons, sometimes for hours, and replayed them at home, listening again and again to memorize the material for exams. In primary school, a teacher once sat beside him to help type notes. But in junior secondary school, that support vanished. There was a different teacher for each subject, no close relationships, and no accommodations. He relied on memory.

Against all odds, he earned full credits, meeting the requirements for admission to The Gambia College (now the University of Education of The Gambia).

Teaching Was Never a Backup Plan

Becoming a teacher was never a result of Alieu’s blindness; it was always his dream. As a child, even while still in school, he would visit the blind school and ask teachers if they were tired, hoping they would let him step in to teach. When he lay down at night, he fantasized about standing in front of a classroom. Teaching was indeed his passion.

After completing his Higher Teachers’ Certificate (HTC) in English, Alieu began teaching in mainstream schools at both junior and senior secondary levels. But again, the system was not ready. At the start of his teaching career, he realized that to teach effectively, he would have to create his own solutions. Out of his own pocket, he bought a laptop and a printer. He scanned printed materials to convert them into accessible digital formats. He printed notes for students because he could not write on the board, dictating notes was unreliable, and he could never be sure students copied correctly.

In one school, he struggled, then he moved to another, and everything changed. The school principal made a decision that transformed Alieu’s teaching experience. Blackboards were replaced with whiteboards, a projector was purchased, solar power was installed to guarantee electricity, and for the first time, Alieu felt fully supported as a professional teacher. He even hired a technical assistant with his own money to support him during lessons. This was where his teaching career truly flourished.

Respect, Discipline, and the Classroom

Like many teachers with disabilities, Alieu has faced moments of disrespect. Once, a student mocked him, dancing and pointing in front of the class. Alieu was not angry, but he understood the importance of addressing it. He reported the incident to the school’s disciplinary committee, not to punish, but to ensure such behavior was not normalized. Beyond that incident, his students treat him like any other teacher. They respect him, listen, and learn.

Outside the classroom, Alieu established a library club, coordinates drama activities, and engages students through music and poetry. His creativity is not separate from his teaching; it enhances it.

Poetry, Music, and Activism

Beyond education, Alieu is a poet with a love for spoken word and music. He has participated twice in the National Poetry Slam of The Gambia, reaching the finals once. His performances, still available online, are expressions of resistance, truth, and lived experience. Poetry, for Alieu, is both art and advocacy.

He is also a disability rights activist, advocating for people with visual impairments in The Gambia. He speaks strongly about inclusive education, the urgent need for accessible learning materials, and the failure to implement the country’s disability law, particularly the provision reserving 15% of jobs for persons with disabilities.

If allowed to speak directly to government leaders, his message would be simple but firm;

Provide accessible books, invest in Braille displays, notetakers, and printing presses, and ensure blind students are not left empty-handed while others receive textbooks.

He speaks with pain about how blind students often sit in classrooms with nothing, no books, no materials, while their peers learn freely. This gap, he says, has damaged countless futures.

His Message to Young Blind People

To young blind people struggling with inaccessible education, Alieu offers honest advice;

Make noise.

Talk about what you are experiencing.

Write about it.

Turn your pain into poetry.

Alieu Jallow’s story is not about overcoming blindness. It is about surviving an unjust system and still choosing to give back.