Australian drill rap group ONEFOUR. Source: ONEFOUR Official | Instagram

The Royal Easter Show and the NSW Police recently announced a ban on “rapper music” following the murder of Pacific young person, Uati “Pele” Faletolu last year.

The Royal Easter Show’s general manager Murray Wilton said:

If you look at the psychology of music … there is scientific fact the type of music that is played actually predicts somebody’s behaviour… There will be no music played [at the show] that is rapper music, or has swearing words through it, or has any offensive language.

This rather comic invention of a new genre “rapper music” was actually aimed at banning, we suspect, “drill” or “drill rap”. This is entirely in chorus with NSW Police Strike Force Raptor, which has spent a disproportionate amount of taxpayer money pursuing, disrupting and generally harassing drill musicians under the premise that their lyrics incite violence or help recruit gang members.

As we point out in our recent paper, drill is a variant of hip-hop. It is musically innovative, lyrically inventive and globally popular. It is also particularly popular among young people in Western Sydney. Its lyrics do often deal with street life and sometimes violent crime, using a particular street vernacular.

But drill is not alone in exploring violent themes. Country music, for example, also has a long tradition of dealing in murder. In popular music, Nick Cave cemented his international reputation with an album of murder ballads.

In fact, there is virtually no evidence to support the claim that music causes crime. What research has shown is that policing music and musicians often criminalises or marginalises young people, particularly young people of colour. It also pushes particular musical genres underground, away from legitimate venues. Moreover, for many artists seeking to emphasis their authentic street-cred, being pursued by police is not really so bad for business.

Two days after the media reports of a ban, in something of an embarrassing backflip, the Royal Agricultural Society of NSW chief executive Brock Gilmour said organisers, not police, had decided to prohibit music containing swearwords:

If there’s rap music that’s quite pleasant and there’s no offensive language, they can play it, that’s not an issue.

What is drill music?

Drill is a subgenre of hip-hop that originated in Chicago in the early 2010s. It is characterised by its aggressive, trap-style beats and lyrics that often focus on themes of violence, crime and life on the streets. The music is often associated with gang culture and has been subject to controversy and criminalisation due to its perceived links to real-life violence and criminal activity.

Drill in Australia was largely pioneered by ONEFOUR, a group of five core members with Pacific Islander background from the Western Sydney suburb of Mt Druitt. They have gained international success and broad popularity, despite having encountered significant obstacles to performing in their own country.

Police have systematically scrutinised their music and excluded them from performing at, among other venues, the Sydney Opera House for the Vivid Festival in 2021, claiming one of their songs could incite violence. The story of ONEFOUR has turned police into musicologists and musicians into criminals.

Music as a crime

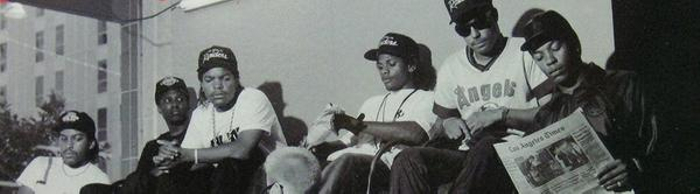

N.W.A. members in 1988 (left to right) Arabian Prince, MC Ren, Ice Cube, Eazy-E, DJ Yella, Dr. Dre. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The criminalisation of rap and hip-hop is not new, as it has long been perceived as a threat to social order and public safety. Artists such as Cypress Hill, Snoop Dogg, and even Rage Against the Machine have faced surveillance, censorship and curtailment.

N.W.A’s song Fuck Tha Police was for a time banned on Australian national youth network triple j, and Akon and Eminem’s performances have been banned due to violence and offensive lyrics. Jazz and punk genres played by marginalised people have also been policed.

Today, hip-hop has become mainstream and respectable, yet criminal justice agencies have become more even proactive in policing and prosecuting particular artists, and there has been an increase in the use of lyrics as evidence in the United States and United Kingdom. The fact is, though, as hip-hop become more popular around the world, crime rates have meanwhile dropped, even in major cities like New York or Los Angeles, the home of gangsta rap. Does this mean hip-hop prevents crime? Well, no, but it does highlight the fallacy of drawing such causal links.

Musicriminology

We know music can touch us emotionally, make us cry, encourage us to dance, and even provide a soundtrack to social change. Scholars have long studied music’s role in protest and resistance – even its role in redemption in correctional settings.The confusion between rap music and the so-called street gangs has been studied, and the salacious pleasures and desires wrapped up in violent or crime storytelling have been analysed by researchers. One of us (Murray) coined the term “musicriminology” to describe these fields of research and scholarship. We have further suggested that police targeting of drill artists constitutes a form of aesthetic policing – the pursuit of rappers police don’t like the sounds, symbols or looks of.

While we can clearly point to the fact that policing practices and social reactions to music can criminalise and stigmatise artists, the link between music and offending behaviour is far more complex. Counterintuitively, for example, researchers found listeners attracted to extreme music (such as certain types of death metal and rap) report positive psychosocial outcomes such as empowerment, joy and peacefulness.

We are not suggesting all music is suitable for all occasions. Most parents would want to keep their young children from watching horror films, just as they might not want them to listen to drill music.

Drill could be best described as a form of music that reflects the lives and street codes of marginalised groups of youth, and does it in a way that fictionalises, embellishes and overemphasises their “gangsta” credentials. It sometimes provides a platform for goading other groups through rhymes.

However, it is unlikely to turn anyone to crime. That is not to say those involved in crime might not also like to listen to it – just as they might like to hear Johnny Cash croon that he “shot a man just to watch him die”.

In anything, blanket bans on musical styles are likely to work against the wellbeing of already marginalised groups, stoking social and cultural division, and providing the context for further criminalisation.