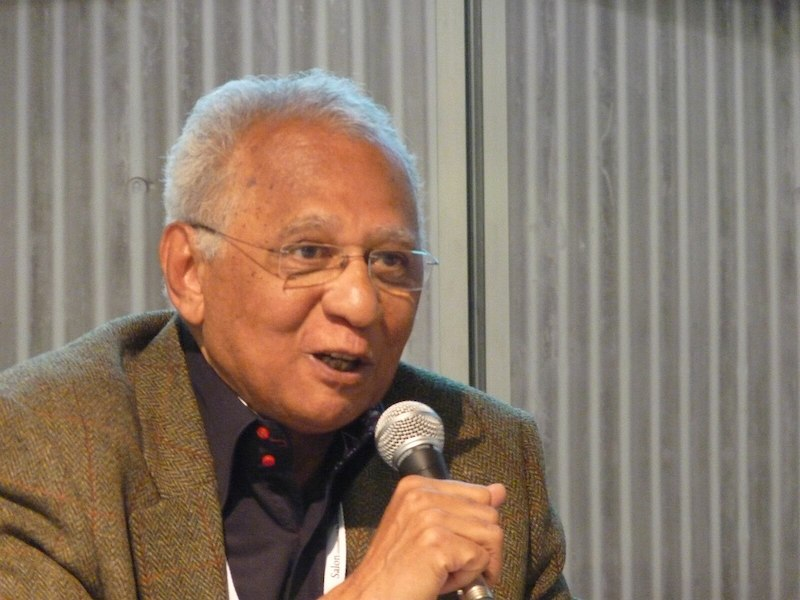

Image: Henri Lopes. Source: Wikimedia Commons

“On the other bank … that is where Henri Lopes now rests,” wrote novelist and journalist Nicolas Michel in a beautiful tribute to mark the passing of the celebrated Congolese author. It’s a reference, of course, to Lopes’ 1992 novel Sur l’autre Rive (On the Other Bank).

Indeed, how can we not imagine Lopes as the character Andélé from his 1990 novel Le Chercheur d’Afriques (The Researcher of Africa), who describes himself as a man “born between the waters”? Lopes, born to mixed ancestry, was a writer who never wanted to be confined to one “bank”. His novels depicted an inclusive range of characters.

Identity is a key theme in his work, as is colonization, its after-effects, and the politics of postcolonial Africa. The novels, driven by a quest for social justice, include meditations on women’s rights, dictatorial regimes, racism, and questioning of certain ancestral traditions. It’s not surprising they are political. Lopes was a teacher-turned-politician who served as prime minister of Congo-Brazzaville.

As a lecturer and scholar of Francophone African literature, I focus here on his literary career. Through his writing, Lopes explored the multiple ethnicities that forged his identity. In the process, his novels offer insights into how humans from different worlds interact. He dares to show that prejudices and racism are a trait shared by all human beings.

Born Marie-Joseph Henri Lopes in 1937 in Léopoldville (today Kinshasa) in what was then the Belgian Congo, Lopes grew up in Brazzaville across the Congo River. His parents were reportedly both mixed race and abandoned by their European fathers at birth.

The Researcher of Africa is a testimony to the multiple identities of those not considered to be of one pure racial group. Andélé finds himself variously labeled: black, half-black, half-white, Indian, Arab, Jewish, West Indian… Lopes, too, was a cultural kaleidoscope. He never belonged to one river bank but rather embarked on boats that sailed between the two.

Lopes started his career as a teacher but would go on to enter politics, finding an affiliation with President Marien Ngouabi’s left-wing Marxist-Leninist regime, between 1973 and 1975 Lopes served as prime minister under the fourth president of the Republic of the Congo. A high-level position beckoned at Unesco, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. In the 1980s and 1990s, Lopes served as deputy director for Africa. In 1998 he was appointed Congo’s ambassador to France. He would serve in the position for 17 years.

But he is best remembered as a writer of fiction.

His literary debut Tribaliques (Tribaliks: Contemporary Congolese Stories) was a collection of short stories. Like that of many of his peers, the work focused on themes of tribalism, postcolonial African politics, and social injustice. Tribaliques received the Grand Prix Littéraire d’Afrique Noire in 1972.

He would go on to publish a dozen works of fiction between 1972 and 2012. The best known of these is the 1982 political satireLe Pleurer-rire (The Laughing Cry). The novel is drenched with witty and barbed insights into the character of postcolonial African politicians. The Researcher of Africa remains one of Lopes’ most studied books.

Image: Cover art fo The Laughing Cry. Souce: Amazon

In 2012 Une Enfant de Poto-Poto (A Child of Poto-Poto) was awarded the Porte Dorée Literary Prize. In 1993 Lopes received the Grand Prix de la Francophonie of the Académie Française for his entire body of work.

The reader of his works will discover honest black men as well as corrupt politicians and dictators. In his analysis of The Laughing Cry, literary scholar Alphonse Dorien Makosso writes that the novel bears a “testament to the act of using literature to address socio-historical issues that border on state terrorism, dictatorship, and political corruption”. According to Togolese writer Sami Tchak:

The author of The Laughing Cry leaves us, through all his books, a burst of laughter that will always question us.

While Lopes portrays despicable colonizers he also offers white characters who view Africa not as a barbaric place without history, but as a continent endowed with civilization long before the arrival of Westerners.

They will also find many endearing female figures there, whose honor and freedom he defended. Whether they are mothers sex workers or women who are stigmatized for being sterile, they occupy an important place in the literary production of Henri Lopes.

Reading Lopes also means delving into Congolese culture. Fellow countryman and novelist Alain Mabanckou stated that Lopes was admired for “his pen crossed by a caustic irony, his fine humor, and his introspection of Congolese morals”.

Congolese customs are revealed in French but interspersed with expressions taken from the languages spoken in Congo. In an interview with Mauritian poet and critic Édouard Maunick Lopes said:

When I write a novel, I am not ideological. I am looking for something other than my place in African literature. At the start I pause, and I say that I am going to speak Congolese, that I am going to speak Congolese in French, writing in this borrowed language that I love.

Even while affirming his Congolese identity, he refused to be confined to an exclusive “bank”. Lopes wanted to write for everyone, and he succeeded. He found a style that married multiple languages and rhythms to represent the diversity of humanity.

In his own words:

We must not be afraid to describe ourselves, even with our faults.

Lopes has not left; he will live on through his writing. Whatever “other bank” he is resting on, one can be sure that he has joined the beloved spirits of Senegalese author and diplomat Birago Diop’s poem The Dead Are Not Dead. With them, Lopes navigates the planets and galaxies, embracing the multiple races and human identities he had been assigned throughout his life.