African Drummer against a backdrop of a Philadelphia Skyline. Generated image using ChatGPT.

When the Drum Speaks

As a child in Indianapolis, I learned early that music is memory. My father and I drove miles each month to the South Side of Chicago, where Black bodies gathered at Kennedy King and Malcolm X Colleges to sweat, heal, and remember. There, African drum and dance classes offered rhythm and restoration, inviting us to step into something ancient and sacred. Even back home at the neighborhood skating rink, I found myself transported by the cadence of wheels on polished wood, evoking something deep and ancestral, a language of liberation embedded in the body.

In the late 1990s, I moved to Philadelphia to attend the University of the Arts for dance. Here, I encountered a living tradition of Black resistance and communal pride built upon a complex history of survival while also serving as a blueprint for joy through drum and dance.

African drumming is one of humanity’s oldest technologies. It has been a tool of communication, healing, and ceremony for tens of thousands of years. Rhythms from Mali, Ghana, Senegal, and beyond endured in the forced crossings of the Middle Passage.

By the early 1700s, colonial authorities saw the drum’s power among African people. The Stono Rebellion of 1739, where African drums coordinated a march for freedom in South Carolina, resulted in widespread bans on drums throughout the colonies. Drums were silenced, but unofficially, new practices emerged, such as percussive hand claps, stomps, and household objects pressed into rhythmic service. The “Drumfolk,” as they came to be called, kept the pulse alive in flesh when wood and hide were outlawed.

Philadelphia, with its growing Black population, felt these ripples. But Black communities carved out spaces to keep ancestral memory vivid. In public squares and marketplaces, enslaved and free people gathered, singing and dancing “after the manner of their several African nations,” preserving identity through the storm. Here, the roots of a unique Black Philadelphia sound and sensibility took hold as a lineage that continues to shape the city’s artistic voice today.

The 1950s and the Black Arts Movement

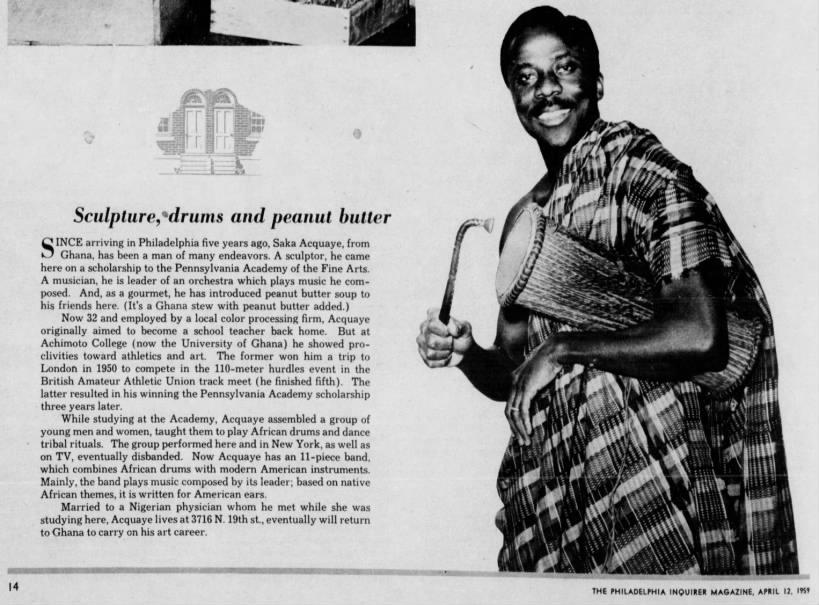

The modern story of African drum and dance in Philadelphia begins in the 1950s, against civil rights struggles and the emergence of Black pride. Ghanaian artist Saka Acquaye (1923-2007) arrived in Philadelphia in 1953, marking a new dawn. Acquaye taught West African drumming and dance to eager young artists, laying the foundation for a generation of leaders. Among his students were Arthur Hall (1934-2000), who founded the Arthur Hall Afro-American Dance Ensemble in 1958, and Robert “Baba” Crowder (1930-2012), whose Kulu Mele African Dance & Drum Ensemble was formed in 1969.

Profile in the Philadelphia Inquirer featuring Saka Aquaye in 1959.

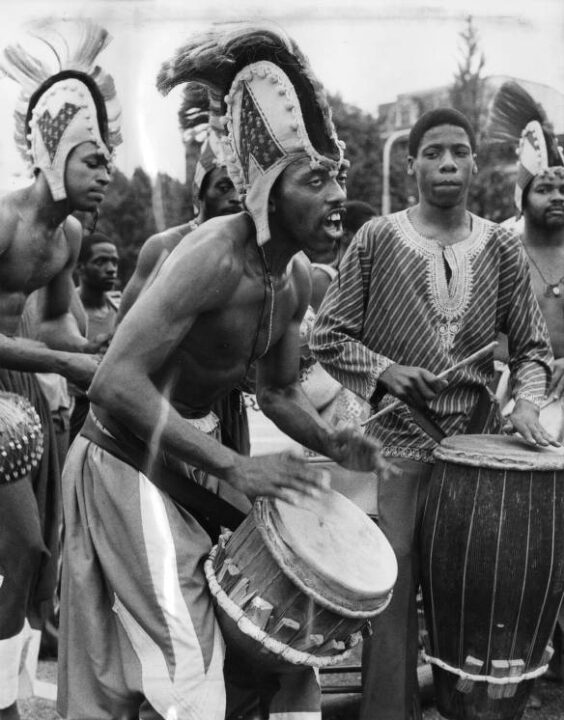

Hall’s company was rooted in tradition but boldly contemporary and became a creative laboratory for exploring African and African American experiences. His work blended Ghanaian forms with the urgent questions of Black life in America, challenging audiences to see dance as a vessel for historical memory and cultural critique. Meanwhile, Crowder elevated West African and Cuban percussion in the city and trained countless young drummers and dancers through Kulu Mele. Their work coincided with the Black Arts Movement, a surge of artistic self-determination that declared Blackness beautiful and worthy of celebration. Dance studios, street festivals, and community theaters flourished, each a sanctuary for culture and community.

Ione Nash (1923-2001), known as “Philly’s great-grandmother of African dance,” emerged as a fierce advocate and mentor in this era. The Ione Nash Dance Ensemble became a fixture at the Odunde Festival and city recreation centers, passing knowledge from elder to youth. “I started dancing because I saw a painting in Rittenhouse Square and knew I needed to move,” Nash once said. “I wanted to give our children a way to remember who they are.”

Arthur Hall Drummers in 1976, Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. Photo by George D. McDowell, courtesy of Temple University’s Urban Archives.

1970s–1990s: Community Power and Global Currents

In the wake of the Civil Rights and Black Power eras, the drum remained a central tool of activism and healing. The creation of cultural centers like Ile Ife, the “House of Love,” founded by Arthur Hall, provided safe havens for art, learning, and resistance. (The North Philadelphia building is now the Village of the Arts and Humanities.) Hall’s ensemble, Kulu Mele, and Nash’s group hosted drum and dance workshops, festivals, and rituals where African American Philadelphians reclaimed their lineage despite ongoing oppression. The drum and dance gatherings were a safe place to commune and define cultural identities based on African heritage, as the crack epidemic and drug wars were rampant in Philly’s Black communities.

This was a time of building. John and Dorothy Wilkie became music and artistic directors at Kulu Mele, traveling to Guinea, Senegal, Ghana, and Cuba to learn from master artists. They brought back techniques, songs, and stories, expanding the company’s repertoire and cementing Philadelphia as a national African drum and dance leader. Nana Korantema Ayeboafo, another pillar, spent years in Ghana studying Akan drumming for healing. She founded Philadelphia’s first all-female percussion ensemble in 1975, a bold act in a field historically reserved for men.

New organizations formed, with leaders such as Kwasi Burgee, Hodari Banks, Vena Jefferson, Jeannine Osayande, Wanda Dickerson, and Oyin Hardy, centered on West African and Afro-Cuban traditions while nurturing new generations of artists. These companies became living repositories of knowledge where polyrhythms, call-and-response, and stories survived and thrived, no matter the era’s challenges.

From Block Parties to Healing Circles: The Drum in Contemporary Philadelphia

Today, the heartbeat of African drum and dance continues in the city’s block parties, healing circles, festivals, and rituals. Fasina Wilkie and Ama Schley, a new generation of younger dancers, now lead Kulu Mele. The company offers classes for children and adults in community centers, public schools, and sacred spaces. Asumane Silla and Cachet Ivey have led open community classes for decades. Ira Bond leads Malidelphia, an organization dedicated to bridging the gap between African immigrant and African American communities.

The influence of these practices can be felt in modern genres, from Afrobeats to hip hop. Philadelphia’s robust Black and African immigrant communities have fostered a vibrant Afrobeats scene, blending highlife, hip hop, and R&B in clubs and on radio stations. The djembe, talking drum, and other traditional instruments have found new homes in jazz, soul, and house music, infusing local and global sounds with the pulse of the ancestors.

Contemporary local musicians like Neptune XXI bridge these worlds, weaving poetry, hip hop, and African drumming into holistic wellness and healing work. “I want to contribute to hip hop culture healingly,” Neptune says. “The drum is how we process, how we reconnect.” Her vision echoes that of earlier generations, using sound to gather, uplift, and transform.

African drumming is central to Philadelphia; it has profoundly shaped music worldwide. The concept of polyrhythm, multiple rhythms played simultaneously, originated in Africa and now underpins everything from jazz to funk, house, hip hop, and pop. The djembe, bata, sabar, and talking drum have been sampled and celebrated by musicians everywhere. In hip hop, the beat machine and drum samples directly reference the telegraphic role of drums in African villages, connecting people across distance and experience.

Producers like Timbaland and J Dilla have cited African drumming as a foundation for their approach. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and Beyoncé’s The Lion King: The Gift brought African polyrhythms, chants, and percussion into the mainstream, drawing on collaborations with West African artists and ensembles. Global genres like Afrobeats and Amapiano—a South African genre built around an electronic log drum—reimagine traditional forms for new generations. Philadelphia’s dance and club music scenes, including house and hip hop, owe much to this enduring rhythmic legacy.

Kulu Mele African Dance & Drum Ensemble.

A Living Archive: Tradition and Transformation

In 2024, I had the privilege of organizing “The Get Together,” a weekend-long gathering of drummers, dancers, and elders at Philadelphia’s Community Education Center. It was not simply an event, but a ceremony, elders guiding youth, knowledge passing hand to hand. “Through dance, we pass ancestral wisdom from our bodies directly into the community’s collective consciousness,” said Mama Wanda Dickerson.

My documentary, Blues People and the Fireside Chat, was an act of collective remembering and a living archive rooted in radical love and shared healing.

Scholars like Dr. Bessel van der Kolk and Resmaa Menakem affirm what practitioners have long known: trauma resides in the body, and embodied practices like African dance can heal wounds invisible to the eye. This tradition is a medicine, a salve, a way home for people fractured by systemic oppression.

African drum and dance are the heart of Black Music Philadelphia – from ‘tangin’ at block parties to the drum circles at Malcolm X Park. They are acts of memory and resistance, carrying the spirit of the ancestors into the present and the future. Dance heals wounds we cannot see.

Philadelphia’s rhythm carries a sound born in Africa, surviving the Middle Passage, reborn in public squares, thriving in clubs and churches, block parties, and healing circles. It is the sound of freedom, a love letter to the past, a blueprint for what is yet to come.

Watch the Trailer for Blues People

This story was originally published by Love Now Media, in collaboration with WURD Radio and Fun Times Magazine, produced with the support of the Philadelphia Journalism Collaborative, a coalition of more than 30 local newsrooms doing solutions reporting on things that affect daily life. Follow at @PHLJournoCollab.

Jeffrey L. Page is an Emmy-nominated choreographer, director, and cultural anthropologist who credits Philadelphia as the city where he “became a man child.” His work blends tradition and innovation, honoring elders and illuminating new paths of liberation through movement and sound.