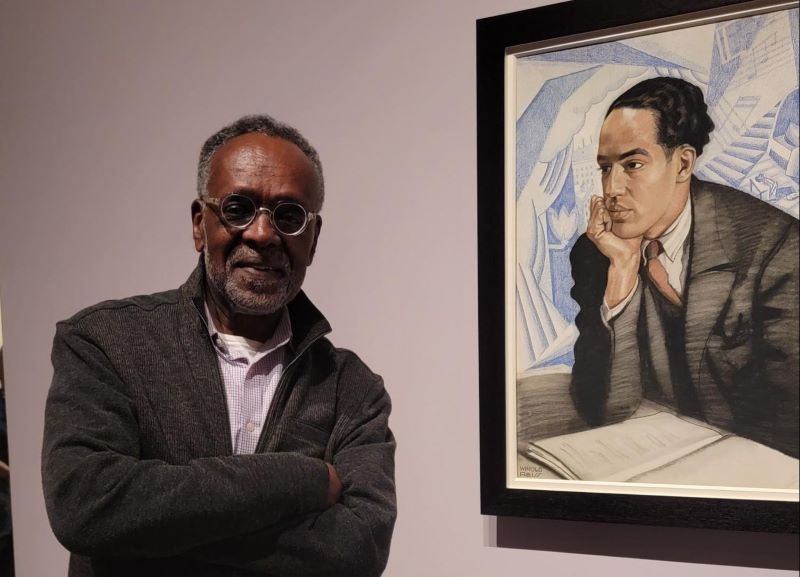

At the Harlem show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York with a painting of Langston Hughes, a fellow Lincoln University Alumni

Oliver St. Clair Franklin, CBE, is a multi-talented figure whose leadership spans diplomacy, cultural advocacy, economic advancement, and global engagement. Through personal experience, institutional influence, and historical knowledge, he brings a vision of how Black communities can think globally and act with purpose.

Unsung Heroes of African Influence on American Civil Rights

As a thinker grounded in history, Franklin shines a light on underreported truths. One of the most compelling is the impact African diplomats had on dismantling American segregation laws.

“People don’t realize it, but African ambassadors helped break segregation,” he says. He describes an incident where a Nigerian ambassador was denied service at a restaurant in Washington, D.C. The fallout led then Secretary of State Dean Rusk to press for policy changes.

“These ambassadors demanded respect under international law. That shifted the ground,” Franklin says. “It helped break down the rules that kept African Americans out.”

His insight reframes civil rights history not as an isolated domestic struggle, but as a global reckoning that connected African liberation movements with Black American activism.

The Cultural Ambassador Who Bridges Global Black Identities

As a diplomat, Franklin has served since 1998 as the Honorary British Consul in Philadelphia. He has worked to strengthen U.S.–U.K. relations while actively encouraging African Americans to view themselves as part of a larger Black world.

“If you talk to West Indians or Africans in Philadelphia, you’ll often discover a relative in London or Manchester,” Franklin says. “It shows how connected we are.”

He sees cultural diplomacy as a way to extend opportunity and deepen understanding. Franklin encourages more African Americans to embrace diplomatic positions. He explains that his role as an honorary consul includes consular assistance, trade facilitation, and cultural diplomacy. He advises individuals who are interested in their culture and a leadership position to “travel to Africa or the Caribbean, build authentic connections, then approach ambassadors to explore becoming a consul.” He explains, “An honorary consul is a citizen of the host country. You must be American. But you also must know the country you’re representing.”

For Franklin, this global awareness is not symbolic. It is practical. He stresses that business-to-business ties, consular services, and public diplomacy are all avenues where African Americans could lead.

The Quiet Power of Cultural Preservation

In one of his biggest accomplishments, Franklin founded the National Black Film Festival in Philadelphia in 2012 to address a gap in how Black stories were shared and portrayed in cinema. He reflects on that work today with pride: “Representation today encompasses all elements of culturally what it means to be a Black person.”

Franklin’s cultural advocacy is also deeply personal. As a longtime collector of African-American literature, he has built an archive now housed at Brown University in Rhode Island.

“Collecting African-American literature was my personal way of building resilience and resistance—a symbol of my quest for humanness,” he says.

These books, from the 1890s onward, were often hidden in the fiction sections of used bookstores, their authors unidentified themselves as Black. Franklin’s determination to rescue these voices reflects a broader strategy of using preservation as a power.

“Our literature carries the history of struggle and the spirit of perseverance,” he says. “Black folks are real thinkers and have been thinkers for hundreds of years.”

In a society that too often erases or forgets, Franklin chooses to recover. His work reminds others to hold onto what matters.

Navigating Setbacks with Wisdom from a Veteran Leader

In the current political climate, Franklin offers measured guidance. He sees the rollback of DEI initiatives and public attacks on diversity as part of a historical cycle.

“History is jagged; it moves forward and back,” he says. “We’re in a period of moving back. We must remain mentally alert and focused.”

His strategy is one of calm vigilance. He counsels younger leaders to keep perspective and not lose confidence. “We’ve been through periods of retrenchment before. This one will pass too,” he says.

Franklin’s long view anchors him. He has lived through the civil rights era, the backlash years, and periods of reform. That experience helps him mentor others through uncertainty without retreating.

With Prince Edward, the Duke of Edinburgh at his home, Bagshot Manor

Empowering Black Professionals in Global Finance and Economic Growth

Franklin is a social influencer who has opened pathways in global finance for Black professionals. Through the City Fellows Program, he allowed mid-level finance workers to gain experience in London’s financial district and economic mobility.

“These weren’t students, he says, adding: “They were already in the field. We gave them global experience and it paid off,”. Some of the program’s alumni now hold leadership roles at major firms in the U.S., Africa, Europe, and Australia.

He makes clear that financial empowerment must be strategic. “We’re really behind because of structural issues,” he says. “Segregation kept us from building equity. People came back from WWII and couldn’t get loans. That’s still affecting us now.”

Franklin focuses on business literacy and sustainable planning. “We must encourage thoughtful planning, not impulsive entrepreneurship,” he says. He draws a sharp line between business and passion; “You can love an idea, but you also have to know how to run it.”

Building Networks and Staying Grounded Through Intentional Leadership

As a mentor and leader, Franklin values clarity and humility. “Leadership is empowering people, sharing a clear vision, and treating everyone with respect,” he says.

He believes in servant leadership and insists on the importance of long-term professional relationships. “Success is networks. For Black professionals in finance, the toughest challenge is knowing who to trust.”

He offers practical advice to younger professionals. Learn the language of finance, deliver consistently, and take responsibility. “If your boss gives you something at 4 p.m. and wants it in the morning, have it ready. No excuses.”

He is also candid about the myths that derail young professionals. “People see athletes making $40 million at 25 and think it’s normal. But that’s not how most of us succeed. It is better to hit the books. Learn something that lasts.”

Receiving a city award from former Mayor Nutter and his wife Lisa Nutter

A Closing Thought from a Life of Work

Franklin says that he believes Philadelphia needs to improve how it supports minority businesses, especially at the middle-market level. “There are companies making $400 million in revenue that still don’t employ people of color,” he says.

He is focused on solutions: More social integration, stronger business relationships, and increased awareness among decision-makers.

When asked what he would have done differently in his career, Franklin doesn’t hesitate: “I would’ve stayed in school longer. Probably done a PhD. It shows how deep you can go into a subject and what you’re capable of managing.”

And perhaps more importantly, he says he would have maintained his early professional relationships more. “Don’t let them float away. Even once a year, just check-in. That matters.”

Hon. Oliver Franklin moves with intention. He thinks, advices, collects knowledge, and speaks in ways that reflect a lifetime of wisdom, study, and service. Whether addressing cultural erasure, financial equity, or global diplomacy, he remains consistent in his messages and firm in his purpose. He is clear about the solution. “We need financial literacy. We need business education. And we need African and West Indian professionals to collaborate more with descendants of enslaved Africans in America.”

His words, wisdom and work serve as a compass “We just have to be serious, focused, mentally alert, the thinker says “This setback is temporary.”

This article is made possible with the support from the following organizations:

Dr. Eric John Nzeribe is the Publisher of FunTimes Magazine and has a demonstrated history of working in the publishing industry since 1992. His interests include using data to understand and solve social issues, narrative stories, digital marketing, community engagement, and online/print journalism features. Dr. Nzeribe is a social media and communication professional with certificates in Digital Media for Social Impact from the University of Pennsylvania, Digital Strategies for Business: Leading the Next-Generation Enterprise from Columbia University, and a Master of Science (MS) in Publication Management from Drexel University and a Doctorate in Business Administration from Temple University.