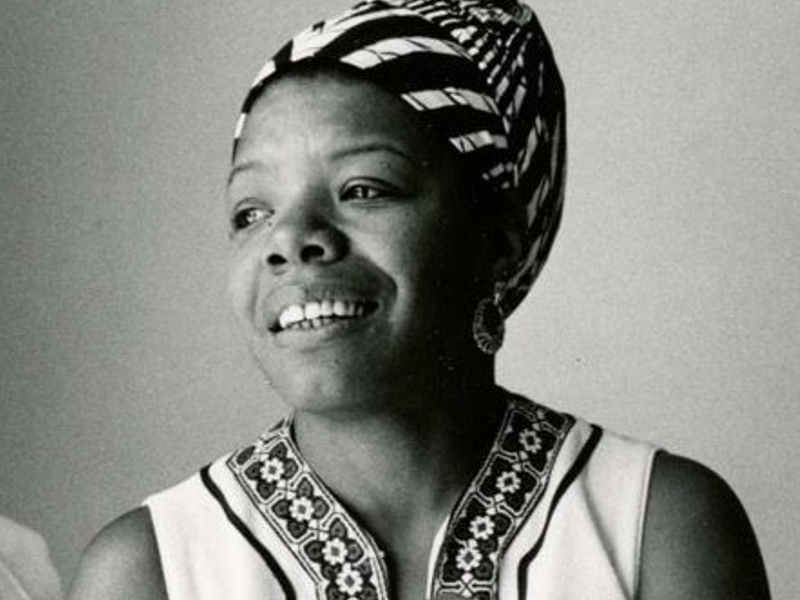

Portrait photograph of Maya Angelou by Jill Krementz, March 25, 1974. Public Domain

On August 28, 1963, a group of activists gathered opposite the US Embassy in the Ghanaian capital of Accra. Inspired by the March on Washington unfolding 5,000 miles away, the protesters carried placards urging the US government to “wipe out racism” and claiming that the US now faced a choice between “civil liberties and civil war”.

In the front row of the demonstration was a face that would later become famous – the American author and poet Maya Angelou.

The Accra march reflected Angelou’s growing engagement with radical politics. Frustrated by American racism and fascinated by African decolonization, she moved to Egypt in 1961 and then Ghana in 1963. In both countries, she found work as a journalist within the state-controlled media. While Angelou’s memoirs give few details about this political work, I’ve spent the last three years tracking down surviving copies of her writing from Egypt and Ghana. These newly uncovered texts demonstrate Angelou’s efforts to link the struggle for civil rights in the US to global campaigns against racism and imperialism.

However, they also suggest she faced censorship and discrimination which tested her skill as a writer and may have ultimately encouraged her to return to the US. Today, Angelou – who was born on April 4, 1928 – is best known for I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969), a vivid account of her childhood in Arkansas. In 1993, she recited one of her most famous poems,On the Pulse of Morning, at the inauguration of US President Bill Clinton.

Angelou’s anti-colonial journalism, by contrast, reveals a new and more radical side to her career during the 1960s. Angelou’s political writing began in New York. Moving to the city to work as a nightclub singer, she soon became close to leftist groups like the Harlem Writers’ Guild and Fair Play for Cuba Committee. These ties encouraged Angelou to submit writing toLunes de Revolución (The Revolution on Monday) – a literary magazine operated by Fidel Castro’s government in Cuba. By searching the magazine’s digital archives, I was able to track down Angelou’s very first publication, Entre Memphis y Cleveland (Between Memphis and Cleveland).

This tense short story follows an African American man narrowly escaping a racist assault and was printed in a special edition of Lunes devoted to the struggle for civil rights.

In late 1960, Angelou met the South African anti-apartheid activist Vusumzi Make at a Harlem Writers Guild party. The two formed an immediate romantic connection and moved to Cairo together in late 1961 to support Make’s work at the African Association, a network of anti-colonial activists sponsored by the Egyptian government.

To pay off Make’s considerable debts, Angelou found work as the Africa editor at theArab Observer, a news magazine with a close relationship to the Egyptian regime. She also began writing for Radio Cairo, Egypt’s international broadcasting service and received extra pay for every script she read herself. This work encouraged Angelou to develop her skills as a political writer. At the Arab Observer, Angelou recalls in her memoirs, that she learned how to produce propaganda “with such subtlety that the reader would think the opinion his own”.

Surviving copies of the magazine suggest that her work was radical and anti-colonial, arguing for “real militancy” in the struggle against apartheid and imperial rule. Radio Cairo, meanwhile, was locked in a competition with British, French, Soviet, and Israeli broadcasters to win audiences across Africa. Egyptian broadcasts certainly helped to intimidate imperial authorities, who grew anxious about the influence of “vitriolic anti-colonial propaganda” in their territories. In response, broadcasters like the BBC began creating and expanding their radio services in an attempt to “counteract the effects of Radio Cairo”.

Maya Angelou (far right) protesting outside the US Embassy in Accra, Ghana, alongside Julian Mayfield, Alphaeus Hunton and Alice Windom (1963). The New York Public Library, CC BY 4.0

As her relationship with Make broke down, Angelou moved again – this time to Ghana, then led by the charismatic socialist Kwame Nkrumah. In Accra, she found a supportive community of African American radicals who, like her, had moved to Africa in the hope of contributing to progressive anti-colonial causes. She also began working as a journalist for state-funded newspapers like the Ghanaian Times and The African Review.

By cross-referencing texts from Angelou’s archive with radio transcripts produced by the BBC, I discovered that she also continued writing for radio. This time, her scripts were broadcast on the African Service of the Ghana Broadcasting System, another international broadcaster which British officials were convinced was “detrimental to [their] interests” in Africa.

Her writing continued to attack racism and imperialism, urging Africans and African Americans to unite against the “common foe” of White supremacy. In her articles and radio talks, Angelou argued that the liberation of Africa from colonial rule could pave the way for the liberation of African Americans from segregationist violence.

Comparing Angelou’s original scripts to broadcast transcripts, however, suggests that her writing also faced political censorship by the Nkrumah regime. In one 1964 program, for example, her references to Ghana’s “token military machine” were replaced with praise for its “military power”, while a critical reference to Africa’s “self-imposed redeemers” was cut entirely.

Angelou also began to face political discrimination. In the wake of a failed assassination attempt on Nkrumah in 1964, paranoid Ghanaian authorities began accusing the African American community of acting as agents for the US.

In her memoirs, Angelou claims to have kept her head down to “avoid the flaming tongues” – but she also wrote an article in the Ghanaian Times denouncing African American moderates as “Uncle Toms” and “slave sellers” who failed to recognize their bondage. As the Nkrumah government began to expel prominent American activists, Angelou may have felt obliged to play to these popular prejudices to avoid being caught up in them herself.

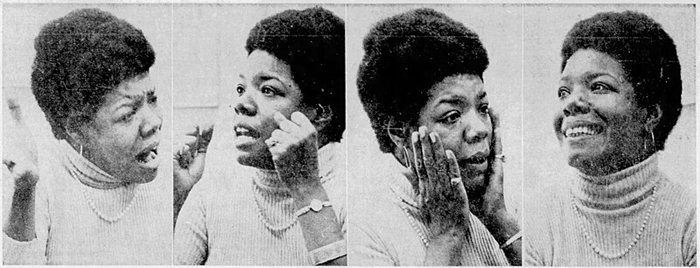

Image: Gallery of portrait photographs of Maya Angelou at Fresno State College by Ryan Marty, February 29, 1972, published with the caption “Four of the 100 faces of Maya Angelou” Public Domain

Angelou returned to the US in February 1965, hoping to work for the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Inspired by Malcolm X’s tours of Africa in 1964, the group aimed to support Black liberation by adopting the tactics of African anti-colonial parties.

Angelou’s plans fell apart, however, after Malcolm X’s shocking assassination. While she continued to write for The African Review, she gradually moved away from journalism and toward poetry and memoirs which would later make her famous.

Together, Angelou’s political writing sheds light on a fascinating moment of solidarity. At the height of the civil rights movement, she joined other African American radicals in turning away from the US and toward Africa. To do so, however, she had to navigate complicated systems of patronage, discrimination, and censorship.

Ultimately, Angelou’s early writing paints a complex, compelling, and all-too-human picture of her career as an anti-colonial activist.