For many immigrants in Philadelphia, finding community can be a challenge.

For Sarah Lumbo — the director of youth science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education for the College of Physicians of Philadelphia — the challenge was one she was eager to engage.

Lumbo first found the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in the summer of 2009, when, as a rising sophomore in the School District of Philadelphia, she participated in the first cohort for any programming at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: the Karabots Junior Fellows Program — now called the Wohlreich Junior Fellows Program.

A first-generation Congolese American woman, Lumbo said she noticed many of her peers in the program were also first-generation and had similar experiences over which they could bond.

“Even though we could identify with our other classmates who were not of African descent, we noticed that we had more of a camaraderie because we were first-generation Africans,” Lumbo said. “We had similarities within how our households were run. A lot of our parents spoke French at home. A lot of our parents came from West Africa — Senegal, Liberia, Togo, Ghana. We kind of had our little clique.”

Lumbo said the first-generation students quickly realized they faced unique challenges. Since their parents didn’t go to school in the United States, they had no familiarity with the American school system, meaning the first-generation students had to proactively discover how to apply to college while simultaneously learning the information they were taught in class, basically on their own.

To address this issue, Lumbo founded the Girls One Diaspora Club, an after-school program to teach high-school-aged girls in Philadelphia who are from Africa or part of the African Diaspora about potential STEM and healthcare career paths, in February 2017.

“Our parents didn’t know how high school worked here,” Lumbo said. “Coming to the (Junior Fellows) program, we got a lot of help serving as that middleman to explain things to our parents from people like Miss Jeanene.”

Jeanene Johnson, assistant director of youth academic programming for the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, has been with the college since 2009. She met Lumbo that summer when she worked on the Karabots Junior Fellows Program and Lumbo was a student in it. They now run the Girls One Diaspora Club together.

“I wasn’t just the kickstart person,” Lumbo said. “I still serve as the coordinator, director, and facilitator. We do it all.”

Along with providing academic support, the program also addresses the unique emotional challenges African immigrants face here.

“Our students deal with a lot, as does any Philadelphia high school student,” Lumbo said. “A lot of our students deal with bullying. They’re not born here in America, and if they are, their backgrounds are heavily cultured. They’re dealing with having to be the first. There’s a lot on their shoulders. We serve as the liaison — especially when it comes to preparing for college — making sure we give them the explanations they need.”

As someone who knows firsthand the emotional toll of those unique challenges, Lumbo said she made sure the curriculum she developed addresses the girls’ emotional well-being as they are taught.

“Many of their schools don’t have a large population of young girls from Africa dealing with the issues that they’re dealing with,” Lumbo said. “There are heavy language barriers. Not everyone is familiar with African culture. A lot of their schools are not familiar with what the home life is like.”

She said the girls who are Muslim will often have to go out of their way to make their school officials aware of different holidays or prayer accommodations.

Since the girls have to navigate the school system differently as first-generation immigrants, Johnson said the program aims to provide them with essential information, including how to get their necessary paperwork, tell their fathers that they’re attending an after-school program when they’re wanted at home immediately after school, and convince their parents that they want to attend college instead of getting married.

“This was new to me because I’m not from directly from an immigrant background,” Johnson said. “I’m learning from these young women how they navigate keeping that 3.0, making sure dinner’s cooked when they get home, and helping mom out.”

Lumbo said letting the girls tell her what challenges they’re currently facing has been critical for developing her curriculum. One challenge she said they face involves managing the roles of student and caretaker simultaneously.

“A lot of us served as mini-parents for our younger siblings,” Lumbo said. “A lot of our parents worked heavy shifts (or) were laborers. Some were even in school themselves.”

Lumbo said the program helps prepare first-generation students for college with SAT preparation and by teaching the girls about financial topics like subsidized and unsubsidized loans, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA), and the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA).

“One of the main things we focus on is public speaking,” Lumbo said. “We, as African women, are in a culture where we are not in positions to speak publicly. Our program, from the first cohort to the current cohort, focuses on building their public speaking craft.”

Each cohort consists of about 12 to 15 girls, according to Lumbo. She said the program has reached over 50 girls since it started in 2017.

“We started with our little core group that we pulled from our other programs and built it each year,” Johnson said. “Each year, we recruit a new cohort of students.”

So far, Lumbo said, the program has included girls from Togo, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea, Mali, Uganda, Senegal, and Mauritania.

The program meets every Tuesday from 4-6 p.m. at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, located at 19 S 22nd St, Lumbo said. She and Johnson are both in the classroom leading these meetings.

Lumbo said the meetings begin with a mental health check-in, during which each girl can share with the group how they’re feeling and anything that might be bothering them.

“We allow our students to go around in a circle and tell us how they’re feeling — mentally, physically, and spiritually — on a scale of one to ten,” Lumbo said.

“When they come in from school, they’ve already had a long day, so we let them have their time to decompress and chat with each other,” Johnson said. “We ask them — how was your day? what’s a highlight from this week? what was challenging this week? — so they can talk about it. More often than not, someone else will say (something like), ‘I had to deal with that too. This is what I did. Did you do this?’”

After the mental health check-in, Lumbo and Johnson let the girls discuss “hot topics.”

“A lot of times, we want the hot topic to be something scientific or healthcare-oriented, but we also let them talk about things that are in the news,” Johnson said. “We always find a way to pivot back to what (the topic) has to do with public health or being a young woman in a certain situation.”

Johnson said discussing hot topics helps her and Lumbo know where the girls are getting their information and “make sure they’re staying on track.”

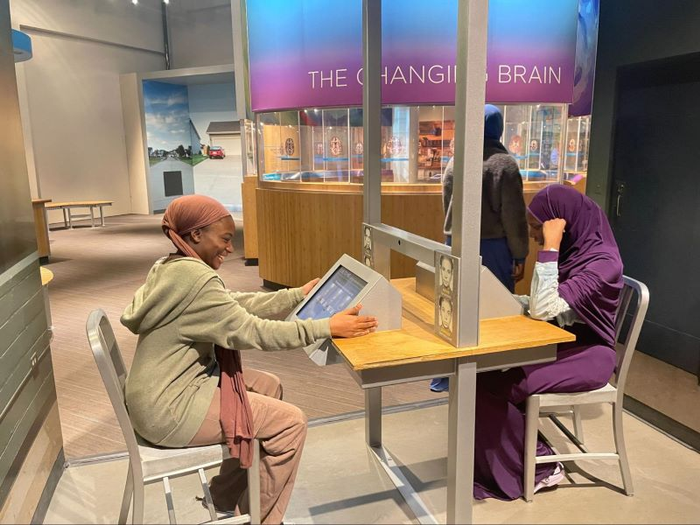

After the icebreakers, instruction begins either with Lumbo teaching a lesson or a guest speaker presenting to the girls. Lumbo said the program also hosts field trips throughout the city to supplement what the girls learn in the classroom.

One trip, according to Lumbo, took the girls to the University of Pennsylvania’s Greenhouse and Growth Chambers to expand on what they learned in the Benjamin Rush Medicinal Plant Garden.

To be eligible for the Girls One Diaspora Club, girls just need to be enrolled in a high school within the Philadelphia School District. An interest in healthcare, medicine, or STEM also helps.

The program accepts girls of any high school age, so students are welcome to apply for as many years as they want, as long as they’re still in high school. Because of this, girls who enter the program as underclasswomen will sometimes come back for multiple summers.

“Reaching them is not just a one-and-done thing,” Johnson said. “A really important part of the program is that it is a sisterhood. The best part is when students who were here the previous year tell their sister, or their cousins, or their new family members who just came over from Africa about the program.”

Johnson said former students from the program will even come back to the college to help current students navigate these problems and share what worked for them. Lumbo said cooperation between students is crucial in helping address their unique challenges.

After almost a decade of hosting the program, Lumbo and Johnson have no shortage of success stories involving girls they’ve reached. One that Johnson recalled involved a young woman from Burkina Faso.

“She had such a beautiful accent, but she was ridiculed in school every time she had to speak. She would always avoid it,” Johnson said. “She got to the point where she said she was on a three (during the mental health check-in) because of a class she was failing and wasn’t going to do the oral part of her report.”

When the other girls in the class asked her why, the girl explicitly said, “I don’t like to speak in front of them because they make fun of me,” according to Johnson.

“Sarah and I said, ‘No, no, no. You’re a strong woman. You’re going to do this,’” Johnson said. “I told her, ‘Yes, you have an accent. Take your time. Speak slowly. You’re going to have your accent. Be proud of your accent.’”

Johnson encouraged the girl to take a glass-half-full approach when she speaks to unfamiliar crowds.

“Do you know what it means? It means you speak two, three more languages than everyone else in that room,” Johnson said. “When they want to laugh at you, ask them, ‘Can you say that in French?’ Don’t let them make you feel bad.’”

The girl remained in the club for three years, Johnson said and gradually became more comfortable speaking in front of an audience as she practiced.

After two years in the program, the girl began to feel more confident, according to Johnson.

“Sarah devised some public speaking events for them to attend and also practice in the classroom,” Johnson said. “(The girl was nervous, but) she had to do it. We filmed it and we practiced with each other. We made it fun.”

By the end of that term, the girl she was proudly doing all of her oral reports, Johnson said.

“She did not care,” Johnson said. “She said her name with her accent and her head held high. She wasn’t trying to sound like anyone else. I will never forget that.”

Johnson urged young students who are part of the African diaspora to cherish their accents.

“If (you have) an accent, just take your time,” Johnson said. “If you’re Russian and have an accent, people will lean in and listen. They’ll give you that patience. If you’re British, they just love it, even if they can’t understand what you’re saying. You’re not any different than that. Hold your head high and say what you’re going to say.”

Lumbo shared a similar story. During the first cohort, she said she noticed students weren’t happy to say their names “the way they should be said.”

“So, we had each young woman come to the front of the classroom and say their name and where they came from,” Lumbo said. “The first day we practiced this, their voices were very low. By the last day, they were loud.”

Lumbo said moments like this show her the curriculum she designed is effectively addressing the girls’ unique challenges.

“A lot of what immigrants go through is giving other people an easier way to address them, rather than making sure other people are aware of how their names should be said,” Lumbo said. “I was able to make them feel happy about saying their name correctly. That is my best memory.”

For Johnson, who’s known Lumbo for 15 years now, watching Lumbo’s progression has been nothing but joy. She said watching Lumbo develop into a dynamic young woman makes her feel “like a mom.”

“We want to make sure every young woman in this program understands that their particular light should not be dimmed,” Lumbo said. “I wish we had a program like this when I was in the program.”

Lumbo and Johnson are currently recruiting for the club’s next cohort. Any interested young women enrolled in a high school in the Philadelphia School District can apply today using the 2024-2025 application.