Marian Anderson photograph and Betsy Ross images (bottom middle, bottom right) Source: Public Domain. All other images cited below.

It’s no secret that Philadelphia is full of history, and while the male figures are often highlighted, we often forget the heroines who made significant contributions.

For centuries, the City of Brotherly Love has been home to some of the strongest, bravest women America has known. Great names like Marian Anderson, Harriet Tubman, and many others made their marks and will forever be remembered for their impact. For someone like Tubman, she will forever be known as an American hero. So much so that since 1990, the US has celebrated her achievements on March 10 – Harriet Tubman Day.

These remarkable women helped shape the direction of the US when it was needed the most, and throughout the Philadelphia region, you will find museums, statues, and buildings that pay homage to some of them.

This Women’s History Month, let’s celebrate these heroines who left an indelible mark on Philadelphia and beyond.

Marian Anderson: The Voice That Defied Segregation (1897-1993)

Marian was the first of three children born to John and Anna Anderson on February 27, 1897, in their South Philadelphia home. She was a Philly girl who displayed vocal talent as a child and became one of the greatest contraltos of the 20th century. Conductor Arturo Toscanini described her voice as one that only came around once in a century.

Photo source – Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

She performed in concert halls where Black people could not attend and endured humiliation and rejection by white society. Her refusal to be silenced in the face of racism led to a defining moment in U.S. history—her iconic performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, which made Anderson a symbol for the ages to come. She had been set to perform at Constitution Hall, but the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) refused to grant her permission due to the color of her skin.

Following the denial, she was approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to perform in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., on Easter Sunday. This concert drew an unprecedented, fully integrated audience of over 75,000 people and a radio audience of millions, becoming a defining moment in the history of civil rights. Her performance was reported to have inspired a 10-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr. to later publish an oratorical describing the experience.

She made history as the first African American to sign with the RCA Victor Recording Company in 1924. She was the first African American artist to solo with the New York Philharmonic to perform on the main stage of the Metropolitan Opera. She sang for presidents and royalty and even received a Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Grammy Award for Lifetime Achievement. Anderson also performed during the March on Washington on August 28, 1963, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Her longtime Philadelphia home houses the Marian Anderson Museum and Historical Society. The museum has memorabilia, books, rare photos, and even films regarding the great contralto’s life.

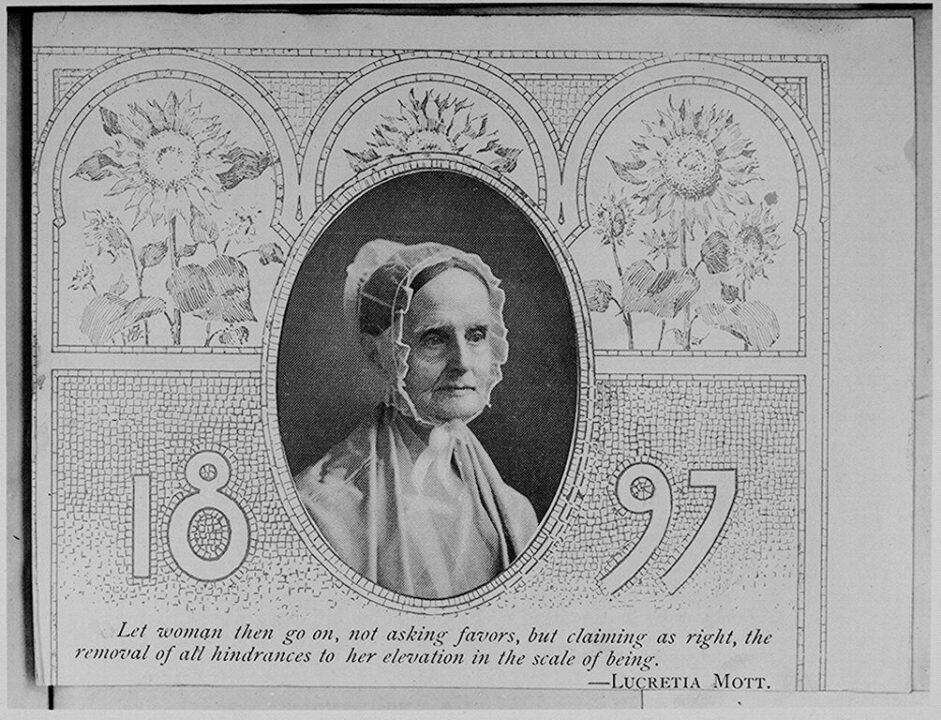

Lucretia Mott – Feminist / Abolitionist (1793-1880)

Perhaps the most famous of women involved in the abolitionist movement, Mott played a fairly prominent role in American history, helping to fight for the end of slavery. Born in Massachusetts, she moved to Philly with her husband around 1811. Her home at 4th and Arch Streets in Philadelphia was a stop on the Underground Railroad. She and her husband opened up their home to slaves escaping on the Underground Railroad.

A Quaker feminist, Mott is best known for her contributions to the women’s suffrage movement. She was one of the founders of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, which allowed Black members — something that was unusual at the time. She helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention, the first of its kind, which launched the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

Photo source – Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

On July 19 and 20, 1848, Mott, alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Mary Ann M’Clintock, Martha Coffin Wright, and Jane Hunt, organized the First Woman’s Rights Convention.

She spent most of her lifetime fighting for equal rights for African Americans and women, and in 1866, she became the first president of the American Equal Rights Association, an organization formed to achieve equality for African Americans and women.

Moth continued to speak out against slavery through the last years of her life until her death on November 11, 1880, at age 87 in Chelton Hills, outside Philadelphia. Today, she’s buried at the historic Fair Hill Burial Ground in North Philly, where you can see her headstone. A Pennsylvania historical marker honoring Lucretia Mott is located at Pennsylvania Route 611 at Latham Parkway, north of Cheltenham Avenue in Elkins Park.

Elizabeth “Betsy” Ross – A Colonial Seamstress (1752-1836)

Perhaps the most well-known of all Philly women, Ross is so beloved and deeply embedded in America’s memory. A Quaker who found herself immortalized in the country’s Revolutionary narrative, she lived in Philadelphia and led a full, fascinating life there. Betsy was a seamstress and worked successfully as an upholsterer for most of her life.

Legend has it that she made the first American flag, but historians have not been able to verify the claim. Though she made flags for the Navy, there is no credible evidence to support the story of Betsy Ross’s involvement with the creation of the first official American flag. She, however, remains an icon of America’s history.

Photo source – Avi1111, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Betsy Ross House, where she is reputed to have made the flag, is one of the most visited tourist sites in Philadelphia. Since the turn of the 20th century, the Betsy Ross House on Arch Street in Philadelphia has been a museum, receiving over a quarter of a million tourists annually. You can tour the place and hear stories about her life.

Hailed as a heroine for her wartime contributions, Betsy died in 1836 at the age of 84. She has been buried in three different locations: Free Quaker burial ground at South 5th St. near Locust, Mt. Moriah Cemetery, and now on Arch Street in the courtyard adjacent to the Betsy Ross House. A major Philadelphia bridge is named in her honor.

Alice Stokes Paul – A Vocal Leader Who Fought For Feminist Causes (1885-1977)

When we talk about feminists of the early twentieth century, Alice was one of the leading ladies. She was an unrelenting and uncompromising feminist fighter who brought the women’s suffrage movement into the national spotlight.

When Alice returned to Philadelphia from England in 1910 after her studies, she became heavily involved with the Women’s Suffrage movement, eventually forming the National Woman’s Party with Lucy Burns. The group was later renamed the National Woman’s Party. She inaugurated the first-ever protest in front of the White House in 1917. During the protest, NWP members known as the “Silent Sentinels” picketed the White House under the Woodrow Wilson administration, making them the first group to take such action.

Photo source – National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Alice spent her life fighting to ensure the U.S. Constitution protects women and men equally. She was a key figure in the push for the 19th Amendment and also played a major role in adding a sexual discrimination clause to Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

She died at the age of 92 on July 9, 1977, and was buried in a Quaker cemetery in Cinnaminson, New Jersey. She is one of the many heroines who had such a big impact on American history. On the centennial of her birth in 1985, the Alice Paul Institute (API) was founded to honor her legacy and continue the fight for equality for all.

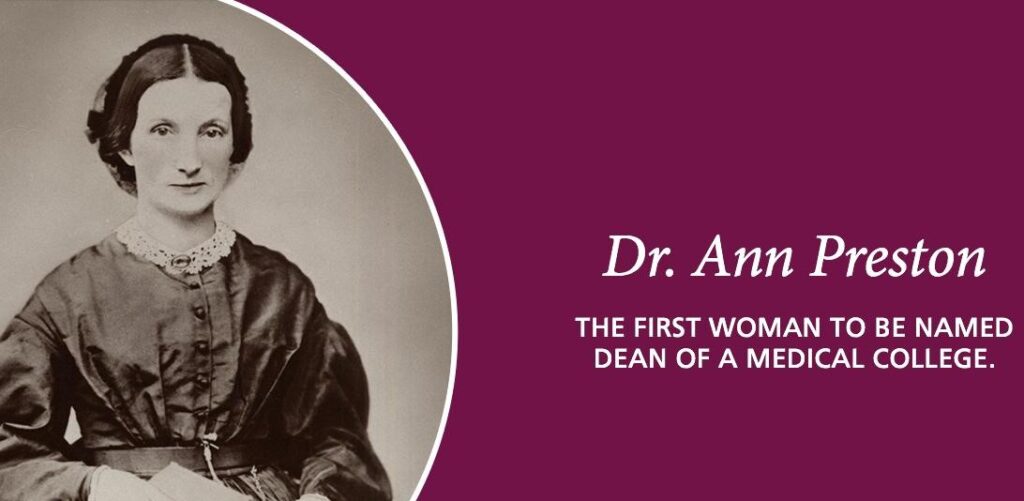

Ann Preston – A Pioneering American Woman Doctor (1813-1872)

A pioneer in the history of women physicians, Ann fought for the rights of women to learn, practice, and teach medicine in the nineteenth century. She spent her entire medical career advocating for women in medicine and helping them achieve their educational goals.

In 1847, she was refused admission to all four local medical colleges in Philadelphia because of her gender. When the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania (later the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania) was founded in 1850, she enrolled, graduating in December of 1851. She went on to become a Professor of Hygiene and Physiology there.

Photo source: Twitter/@AAMCtoday

She founded the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a nursing school. She became the first woman dean of the Female Medical College in 1866 and trained the first female African-American and Native-American doctors. At this time, women doctors were barred from all other hospitals.

Ann began to campaign for the right of her female medical students to attend clinics in the larger hospitals in Philadelphia. With time, women were gradually accepted in more and more hospitals.

She continued to serve at the college and the Women’s Hospital until she died on April 18, 1872.

Caroline Lecount – A Trailblazer For Civil Rights And Education (1846-1923)

A noted civil rights activist, LeCount was a force to be reckoned with. Often referred to as “Philadelphia’s Rosa Parks,” she fought for desegregation in Philadelphia’s public transportation system.

Photo source – YouTube/@PhiladelphiaTheGreatExperiment

She is credited with being responsible for Philadelphia passing a law in 1867 to ban segregation on public transport. After the integrated streetcar legislation was passed, LeCount was among the women activists who would try to board streetcars, and when denied, took legal action. When a conductor refused to stop for her, LeCount, just 21 at the time, filed a complaint with the police, eventually forcing the driver to pay a $100 fine.

She was also an activist for African-American children’s education, standing up to the school board of the Wilmot Colored School to insist a Black colleague become principal because “colored children should be taught by their own,” reports noted.

LeCount was engaged to voting rights activist Octavius V. Catto, who was murdered on Election Day on October 10, 1871, for registering African-Americans to vote. After his death, she remained unmarried and continued his work. She died on January 24, 1923, and was buried on January 27 at Eden Cemetery.

Photo source – Instagram/rename_taney

In 2023, Caroline LeCount finally got a tombstone in Eden Cemetery in Collingdale 100 years after her death.

In 2024, Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker signed into law to make civil rights activist LeCount the first Black woman with city streets in her name.