Maya Angelou, Source: Public Domain. Langston Hughes, Source: Public Domain. Gwendolyn Brooks. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Amiri Baraka, Source: David Sasaki CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons, Nikki Giovanni, Source:

Kingkongphoto & www.celebrity-photos.com, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

The poetic voice of Black America has influenced not only literary space but cultural movements and social change throughout United States history. These poets have written works that captured struggles, celebrated triumphs, and imagined more equitable futures; while also pushing the limits of American literature through how their poems are constructed, the innovative forms they utilize, and their nuanced use of language. Their poems have served as rallying cries for movements, solace for mourners, and reminders of the resilience and creativity of African Americans. This piece is a celebration of five towering figures that, through their words, continue to speak across time and inspire ground-breaking literature and social change.

The Evolution of Black Poetry in America

Black poetry in America grew out of a massive contradiction–a nation built on a notion of liberty participates in enslavement and oppression. From the earliest slave narratives and spirituals to present-day spoken word, Black poetic expression has been able to navigate this contradiction to create art that bears witness to suffering while also affirming humanity and dignity. The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and early 1930s served as the first major flowering of Black poetry as an American art form. During the same time as the Great Migration, the cultural movement created urban communities where art and activism thrived. Black poets began developing forms and themes that expressed their lived experiences and challenged white America.

Following World War II, Black poets increasingly engaged with civil rights struggles, using their art as vehicles for social change. The Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, often described as the cultural wing of the Black Power movement, represented another revolutionary moment. Poets rejected Eurocentric aesthetics in favor of work that directly addressed Black communities and promoted liberation.

Source: Created in ChatGPT by Anand Subramanian

The five poets highlighted here span these various movements, each contributing uniquely to this rich tradition while consistently expanding the possibilities of language.

Maya Angelou:

Maya Angelou stands as one of America’s most beloved literary voices, whose work transcended the boundaries of poetry to impact broader cultural and political space. Born Marguerite Johnson in St. Louis, Missouri, Angelou’s extraordinary life journey informed her powerful writing and activism.

Source: 10th Anniversary of the Death of Maya Angelou | British Online Archives (BOA)

Before achieving literary fame, Angelou led a remarkably diverse career. She worked as a singer, dancer, actress, composer, and became Hollywood’s first female Black director. However, it was as a writer—particularly as a poet and memoirist—that she made her most enduring mark. Alongside her artistic pursuits, Angelou was deeply involved in the Civil Rights Movement, working with both Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, embodying the connection between art and activism that characterized much of Black literary expression.

Angelou’s most celebrated work, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” (1969), revolutionized American literature as an unflinching account of her early years. The memoir courageously addressed her experience of childhood sexual assault and its aftermath—including a period of mutism lasting five years. During this silent period, Angelou developed a profound love for language, reading works by both Black authors like Langston Hughes and W.E.B. Du Bois and canonical white writers. This immersion in literature prepared her to eventually find her voice—one that would resonate with millions.

The impact of “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” extended far beyond literary circles. The memoir was revolutionary in its candid exploration of personal trauma and societal injustices, and its willingness to address taboo subjects empowered survivors to share their stories without shame. Through her candid exploration of racism, sexism, and violence alongside moments of joy, love, and self-discovery, Angelou created what many readers experience as both a mirror that reflects the experiences of marginalized individuals and a window that allows readers from all walks of life to glimpse into the world of adversity and resilience.

Angelou’s status as a national treasure was confirmed through numerous honors. She received the Presidential Medal of Arts from President Bill Clinton in 2000 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama in 2010, along with over 50 honorary degrees. More importantly, her words continue to inspire generations with their unflinching truth-telling and persistent affirmation of human dignity in the face of oppression.

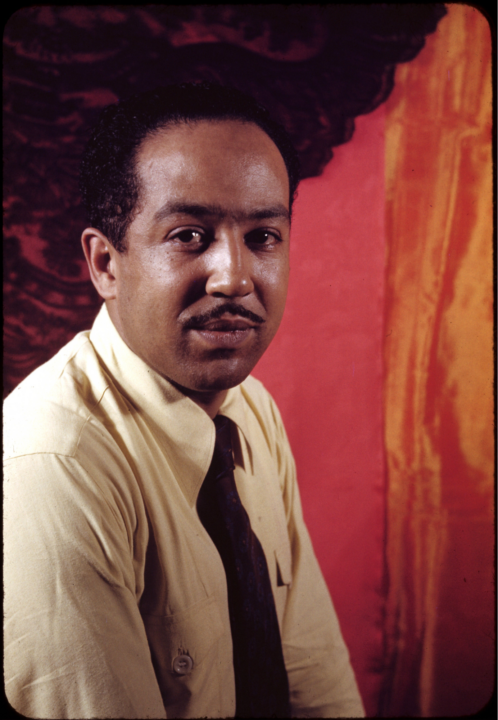

Langston Hughes:

Langston Hughes emerged as perhaps the quintessential poet of the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural flowering of Black arts and letters that transformed American culture in the 1920s and early 1930s. As one of the movement’s “leading lights,” Hughes not only produced poetry of enduring significance but also articulated a philosophy of Black art that would influence generations of writers to follow.

Source: File: Langston Hughes by Carl Van Vechten.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

In a literary industry where many questioned whether distinctly “Negro art” could or should exist, Hughes took a bold stance. Responding to an article dismissing the concept of Black art, Hughes wrote “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” a manifesto declaring, “The younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our dark-skinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too.” This declaration rejected assimilationist tendencies and affirmed the value of authentic Black expression, establishing a philosophical foundation for the Harlem Renaissance and later movements.

Hughes’s poetic innovation was equally significant. He pioneered the incorporation of Black vernacular speech and the rhythms of jazz and blues music into poetry, creating a style that was simultaneously accessible and sophisticated. His 1926 collection “The Weary Blues” exemplified this approach, with poems that captured the cadences of Black musical forms while addressing the complexities of Black life in America. Though some critics dismissed his work as “low-rate” because of these innovations, Hughes persisted in developing a poetic voice that authentically represented the Black American experience rather than conforming to Eurocentric literary standards.

What made Hughes’s work particularly significant was his ability to combine formal innovation with deep engagement with the social and political issues facing Black Americans. His poems spoke to the everyday experiences of working-class Black people while also addressing broader systems of racism and inequality. This combination of aesthetic experimentation and political consciousness established a template that many subsequent Black poets would follow.

Hughes’s influence extended beyond his writing through his role as a cultural connector and mentor. He built relationships with fellow artists across disciplines and generations, helping to create the sense of a collective movement rather than simply individual achievements. His legacy lives on not only in his widely taught poems like “Harlem” (often referred to by its famous opening line, “What happens to a dream deferred?”) but also in the tradition of socially engaged, formally innovative Black poetry that continues to thrive today.

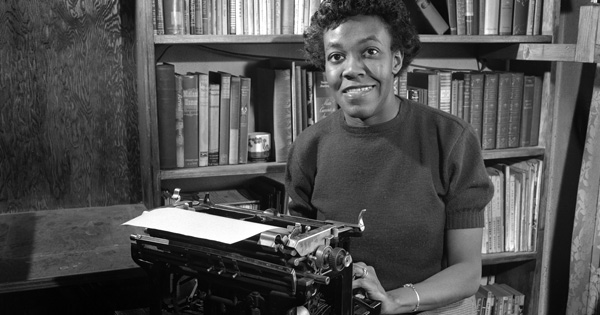

Gwendolyn Brooks:

Gwendolyn Brooks stands as a towering figure in American poetry, whose work bridged multiple eras and approaches to Black literary expression. Her historical significance is marked by numerous firsts: she was the first Black poet to win the Pulitzer Prize, the first Black woman to serve as a Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (a position now known as Poet Laureate), and she held the position of Illinois poet laureate for an impressive 32 years. But beyond these accolades, Brooks’s true achievement lies in her intimate, incisive portraits of Black urban life and her ability to evolve artistically while maintaining her commitment to her community.

Born in Topeka, Kansas, but raised in Chicago, Brooks benefited from parents who supported her literary aspirations from an early age. Her mother, a schoolteacher and classically trained pianist, and her father, a janitor with dreams of becoming a doctor, encouraged their daughter’s passion for reading and writing. This encouragement bore early fruit—Brooks published her first poem at age 13 in “American Childhood” magazine and was published regularly in the “Chicago Defender” by age 17. This precocious beginning launched a career that would span most of the 20th century and leave an indelible mark on American letters.

Brooks’s early collections, “A Street in Bronzeville” (1945) and the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Annie Allen” (1949), established her as a poet of remarkable precision and empathy. Through close observation and formal sophistication, Brooks documented the lives of her Chicago neighbors with dignity and complexity, refusing both romanticization and condescension. Her ability to combine technical mastery with authentic representation of Black experience earned her immediate critical acclaim.

Throughout her long career, Brooks maintained an unwavering focus on Black lives while continually refining her craft and responding to changing social contexts. Her work demonstrates that political commitment and artistic excellence are not opposing values but can mutually reinforce each other. For generations of poets who followed, Brooks provided a model of how to sustain a lifelong dedication to both community and craft.

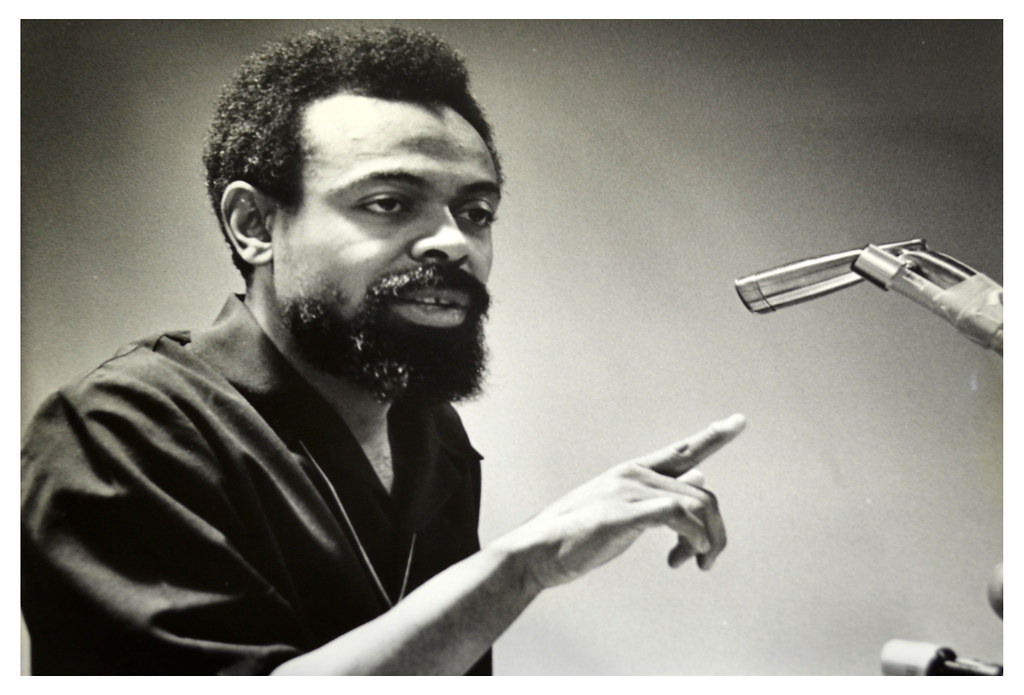

Amiri Baraka:

Amiri Baraka, born LeRoi Jones, stands as one of the most controversial and transformative figures in American poetry of the late 20th century. His evolution from Beat poet to Black nationalist to Third World Marxist tracked alongside—and often catalyzed—major shifts in Black cultural and political consciousness.

Source: Baraka speaks on Black culture at Howard: 1973 | Imamu Amiri… | Flickr

Born in 1934 in Newark, New Jersey, Baraka began his career as LeRoi Jones, a poet associated with the predominantly white Beat movement and New York School of Poetry. His early work, including the collection “Preface to a Twenty-Volume Suicide Note” (1961), displayed formal experimentation influenced by modernist poetry while beginning to explore themes of alienation and identity. During this period, he also founded Totem Press and co-edited the influential literary magazine “Yugen,” which published work by Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and other leading Beat writers alongside emerging Black voices.

Baraka’s artistic and political trajectory changed dramatically following the assassination of Malcolm X in 1965. Rejecting his former associations with white avant-garde circles, he moved to Harlem, founded the Black Arts Repertory Theatre/School, and changed his name to Amiri Baraka. This transformation marked the beginning of the Black Arts Movement, which Baraka not only participated in but was largely defined through both his creative work and his cultural organizing.

Baraka’s poetry from this period, including collections like “Black Magic” (1969) and “It’s Nation Time” (1970), exemplified the militant aesthetic of the Black Arts Movement. These works were characterized by their revolutionary fervor, their celebration of Black cultural forms, their confrontational rhetoric, and their explicit rejection of white aesthetic standards. Poems like “Black People!” and “SOS” became anthems of the movement, merging artistic expression with calls for political action.

What distinguished Baraka’s work was not just its political content but its formal innovation. He incorporated elements of jazz, particularly free jazz, into his poetic structure and performance style. His readings, often accompanied by musicians, transformed poetry from a solitary, page-bound experience into a communal, multisensory event. This approach reflected Baraka’s belief that revolutionary art should not only describe reality but transform it through active engagement with audiences.

Throughout his transformations, Baraka remained a controversial figure, drawing both ardent admiration and fierce criticism. What cannot be denied is his central role in redefining the relationship between poetry and politics in American culture, creating work that refused to separate aesthetic concerns from urgent questions of power, identity, and liberation.

Nikki Giovanni:

Nikki Giovanni emerged in the late 1960s as one of the most distinctive and accessible voices of the Black Arts Movement, and over more than five decades has evolved into a beloved elder stateswoman of American letters. Born Yolande Cornelia Giovanni Jr. in 1943 in Knoxville, Tennessee, Giovanni’s early life was shaped by the civil rights struggles of the American South, experiences that would inform her passionate and direct poetic voice.

Source: Poet Nikki Giovanni dies at 81: NPR

Giovanni’s career began explosively with her first collection, “Black Feeling, Black Talk” (1968), followed quickly by “Black Judgement” (1968) and “Re: Creation” (1970). These early works established her as a poet unafraid to express righteous anger about racial injustice while also celebrating Black culture and community. Poems like “Nikki-Rosa” complicated simplistic narratives about Black childhood by emphasizing the love and joy that existed alongside economic hardship, while more confrontational pieces like “The True Import of Present Dialogue, Black vs. Negro” challenged complacency within Black communities.

What has distinguished Giovanni throughout her career is her remarkable ability to evolve while maintaining her essential voice and values. Unlike some of her contemporaries from the Black Arts Movement, Giovanni successfully transitioned from the revolutionary fervor of the late 1960s to address the changing concerns of subsequent decades without compromising her commitment to Black empowerment and social justice. Her later collections, including “Those Who Ride the Night Winds” (1983), “Love Poems” (1997), and “Bicycles: Love Poems” (2009), expanded her thematic range to include more personal reflections on love, loss, and human connection.

Giovanni’s influence extends far beyond her published poetry through her dynamic presence as a speaker and performer. Her recordings, including the album “Truth Is On Its Way” (1971), which combined her poetry with gospel music, brought her work to audiences who might never have encountered it on the page.

What makes Giovanni particularly significant is her accessibility without simplification. Her work employs straightforward language and often conversational tones, making it immediately engaging to readers regardless of their familiarity with poetic conventions. Yet within this accessible style, she addresses complex issues of identity, power, and human relationships with nuance and depth. This combination has made her not only a critical success but also one of America’s most beloved poets, whose work appears in school curricula nationwide.

Interweaving Themes:

Across the works of these five seminal poets—Maya Angelou, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, Amiri Baraka, and Nikki Giovanni—several interconnected themes emerge, creating a tapestry of Black poetic expression that spans multiple generations and movements. While each poet brought their unique perspective and style to their work, their collective output reveals both continuities and evolutions in how Black poets have addressed fundamental questions of identity, justice, and artistic purpose.

Perhaps the most persistent theme across all five poets is the tension between bearing witness to oppression and celebrating resilience. Hughes’s blues-infused poetry acknowledged the harsh realities of racial discrimination while finding beauty and dignity in everyday Black life. Similarly, Brooks’s precise portraits of Chicago’s South Side residents never shied away from depicting hardship but always recognized the full humanity of her subjects. Angelou transformed her trauma into a universal story of overcoming, while Baraka’s revolutionary verse sought to catalyze resistance against systemic injustice.

Another significant thread connecting these poets is their engagement with language itself—specifically, their efforts to create forms that authentically expressed the Black experience rather than conforming to Eurocentric standards. Hughes pioneered the incorporation of Black vernacular and musical forms into poetry, a project that Baraka extended through his jazz-influenced experimental structures. Brooks worked within traditional forms while subtly subverting them to capture the rhythms and realities of Black urban life.

The relationship between art and activism represents another crucial theme across these poets’ work. All five understood poetry not merely as self-expression but as a tool for social change. Hughes’s “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain” articulated a vision of art that was politically engaged without being propagandistic. Brooks demonstrated how attention to craft could enhance rather than diminish political impact. Baraka explicitly rejected the separation of aesthetics from politics, while Giovanni showed how even love poems could contain revolutionary potential by centering Black experiences of joy and connection.

Finally, these poets collectively chart an evolution in how Black identity has been conceived and expressed in American poetry. From Hughes’s Harlem Renaissance explorations of racial consciousness to Baraka’s Black nationalist phase to more intersectional approaches that consider how race interacts with gender, sexuality, and class, these poets have continuously expanded and complicated understandings of Blackness in American culture.

Conclusion

The legacy of these poets extends far beyond literary circles. Their words have provided comfort during national tragedies, inspiration during social movements, and frameworks for understanding complex social realities. When protesters carry signs quoting Angelou’s declaration that “still I rise,” when activists invoke Hughes’s question about “a dream deferred,” or when students discover themselves in Giovanni’s celebrations of Black childhood, we witness the ongoing impact of these literary giants.

As readers in this complex and uncertain century, we have an opportunity to not only appreciate these poets’ historical significance but also to engage with their work as a living resource for navigating current challenges. Their poetry offers models of how to confront injustice without losing sight of beauty, how to acknowledge pain while affirming joy, and how to use language as a tool for both personal and collective liberation.

We invite you to deepen your engagement with these poets by reading their collections in full, attending poetry readings and performances in your community, supporting contemporary Black poets who carry forward these traditions, and sharing these literary treasures with others. By doing so, you participate in ensuring that the profound legacy of Black poetry in America continues to enrich our cultural space and inspire movements for social change for generations to come.

Anand Subramanian is a freelance photographer and content writer based out of Tamil Nadu, India. Having a background in Engineering always made him curious about life on the other side of the spectrum. He leapt forward towards the Photography life and never looked back. Specializing in Documentary and Portrait photography gave him an up-close and personal view into the complexities of human beings and those experiences helped him branch out from visual to words. Today he is mentoring passionate photographers and writing about the different dimensions of the art world.