More than 300 courageous Black nurses uprooted their lives in the Jim Crow South to seek economic opportunity as nurses caring for tuberculosis patients at Sea View Hospital in New York from 1928 to 1960. Black nurses have played a crucial role in shaping the profession’s history. The profession began to change when Mary Eliza Mahoney became the first Black nurse to graduate from nursing school and be professionally licensed. Since that day in 1879, African American nurses have continued to strive for equality in the profession. Yet, for too long, many of nursing’s most powerful stories have been untold. Among these luminaries stand Sojourner Truth, Susie King Taylor, Harriet Tubman, Adah Belle Thoms, and Della H. Raney — these eight remarkable women whose courage, resilience, and dedication also paved the way for future generations of nurses.

Mary Eliza Mahoney

While many African Americans served as nurses before her, Mary Ezra Mahoney often carries the distinction of being the first Black nurse in history to earn a professional nursing license in the U.S. and the first to graduate from an American nursing school. Born to freed slaves, she worked as a janitor, cook, washerwoman, and nurse’s aide for 15 years at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. After those 15 years, Mahoney entered the nursing graduate program at 33. Mahoney completed the rigorous 16-month program sealing her place in history as the first African American licensed nurse.

In 1896, she joined the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada but faced racial discrimination as the association’s members were unwelcoming of Black nurses. The discrimination led Mahoney to establish the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) in 1908. She served as a lifetime member and chaplain to the organization. During her nursing career, Mahoney also served as director of the Howard Orphanage Asylum for Black Children from 1911 to 1912.

In 1908, Mahoney co-founded the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). This association was vital because, at the time, Black nurses were not allowed to join the American Nurses Association (ANA). The NACGN fought racial discrimination in the nursing profession and uplifted Black nurses, and in 1951, the association merged with the ANA. After 40 years of service as a nurse, Mahoney retired, but continued to lead the charge against discrimination and pointed her efforts toward women’s rights. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1993. The Mary Mahoney Award, founded by the NACGN in 1936 is still awarded to nurses by the ANA.

Mabel Keaton Staupers

A visionary leader and advocate for racial equality in nursing, Mabel Keaton Staupers played a pivotal role in desegregating the nursing profession and expanding opportunities for African American nurses. As the executive secretary of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN), Staupers led a relentless campaign to end racial discrimination in nursing education and employment. While working in Washington, D.C., and in New York, Keaton organized the inpatient clinic for African Americans with tuberculosis at the Booker T. Washington Sanatorium, where she served as the Sanatorium’s first superintendent from 1920 to 1922. This clinic was one of the few facilities in New York that allowed Black physicians to treat their patients.

Staupers served as the executive secretary for the Harlem Tuberculosis Committee from 1922 to 1934. Continuing her mission of health promotion, in 1934 Staupers became the first Executive director of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NAGN), where she served until she became the organization’s president in 1949. Staupers had been a member of the organization since 1916, while she was still attending nursing school. Staupers initiated a campaign to influence the U.S. Army to eradicate its discriminatory policy that banned Black nurses from entering its ranks. In 1944 Staupers met with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt to describe the dire circumstances Black nurses were facing. In 1945 the U.S. Army opened its Armed Forces Nurse Corps to all applicants regardless of race. Staupers documented her long struggle in No Time for Prejudice: A Story of the Integration of Negroes in Nursing in the United States. For her fight against discrimination, Staupers was awarded the Spingarn Medal by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1951.

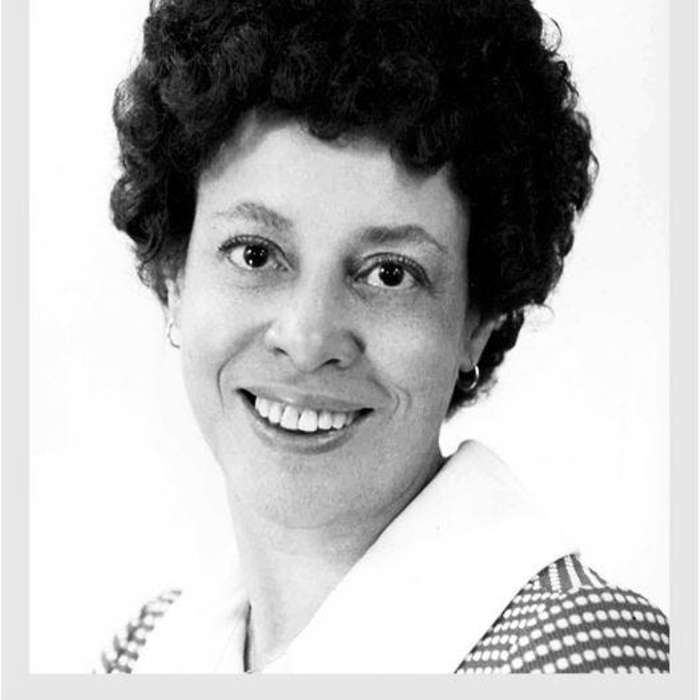

Betty Smith Williams

As a trailblazing nurse educator and advocate, Betty Smith Williams dedicated her life to advancing diversity and inclusion within the nursing profession. Williams earned her bachelor’s degree in zoology from Howard University. Williams graduated with a doctorate from Case Western Reserve University’s (CWRU) School of Nursing in 1954, becoming the first Black nurse to graduate from that school. In 1956, Williams became the first Black person to teach at both the college and university level in California. She was hired to teach public health nursing at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

In 1971, Williams, who co-founded the Council of Black Nurses in Los Angeles three years earlier, and 17 other national nursing leaders met in Cleveland and approved her motion to establish the National Black Nurses Association (NBNA). At the time, she was an assistant professor in the School of Nursing at the University of California, Los Angeles. She became the first African American to earn a Ph.D. in nursing education, paving the way for future generations of minority nurses. Williams’ tireless advocacy efforts focused on promoting cultural competence and equity in healthcare, leaving an enduring impact on nursing education and practice.

Estelle Massey Osborne

Estelle Massey Osborne broke down barriers with her professional accomplishments. Osborne received a teaching certificate from Prairie View State Normal and Industrial College but decided to move into nursing after she was nearly killed in a violent incident while teaching at a public school. She joined the first nursing class of St. Louis City Hospital and became a head nurse there after graduating in 1923. At that time, only 14 of the nation’s 1,300 schools for nursing were open to Black applicants. The American Nursing Association did not accept Black nurses as members, and the US Navy categorically refused to enlist them. Yet for Osborne racial barriers were only meant to be overcome. She received the first scholarship awarded to a Black nurse by the Julius Rosenwald Fund in 1928.

She became the first Black nurse in the United States to earn a Master’s degree in 1931, as well as the first Black instructor at New York University in 1945. Osborne defied a system built on racism to help provide quality healthcare for Black Americans. After she graduated, she went to work for the Rosenwald Fund as a researcher, studying rural life in the deep South and investigating ways to bring better health education and service to rural Black communities. With the country at war, Osborne was hired in 1943 as a consultant to the Coordinating Committee on Negro Nursing for the National Council for War Service. That year, Congress passed the Bolton Act in response to the severe shortage of nurses at home and in the military overseas. Osborne helped to ensure that Black nurses benefited from the $160 million the bill provided for nursing education and financial aid. Her work also significantly expanded the number of nursing schools that accepted Black students. Osborne’s influence was also pivotal in convincing the US Navy to lift its color ban in 1945. McGruder revealed that Osborne had had a strategic ally in her efforts, Eleanor Roosevelt.

In 1946, she became the first Black faculty member at what is now NYU Rory Meyers College of Nursing. Osborne was also elected President of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). In 1946, she received the Mary Mahoney Award for her efforts to broaden opportunities for Black nurses to move into the mainstream of professional nursing. She forged an essential relationship with the American Nurses Association before the program merged with the NACGN in 1951, and she continued her service in organizations and movements in which she could make a lasting difference.

Hazel W. Johnson-Brown

A pioneering military nurse, Hazel W. Johnson-Brown triumphed in the face of adversity as the first Black woman to become a U.S. Army general and the first Black chief of the Army Nurse Corps. As a child, Johnson set a goal to become a nurse. She first applied to the Chester School of Nursing but was denied admission because she was Black. Steadfast in her resolve and transcending many obstacles, she instead began training at the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing in New York, graduating from this institution in 1950. Johnson-Brown enlisted in the United States Army in 1955, seven years after President Harry Truman eliminated segregation in the military.

In the 1970s, she became the director of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Nursing. It was in 1979 that Gen. Johnson-Brown made history when she was promoted to brigadier general and simultaneously commanded 7,000 nurses in the Army Nurse Corps. She trailblazed as the first Black woman and the first chief with an earned doctorate in the Department of Defense to achieve that distinction. Her career was distinguished she won many a medal, including the Army Distinguished Service Medal, and was awarded Army Nurse of the Year twice. She was also awarded a Meritorious Service Medal and Army Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster. In June 1996, General Johnson-Brown was appointed Professor Emeritus, College of Nursing and Health Science, George Mason University. She remained actively involved on the college’s nursing advisory board until she passed away in 2011.

Goldie D. Brangman-Dumpson

Goldie D. Brangman-Dumpson was an American nurse and educator. Brangman-Dumpson started as a volunteer for the Red Cross in 1940. Brangman-Dumpson attended the Harlem Hospital Center’s nursing program and graduated in 1943. Brangman-Dumpson was a co-founder of the School of Anesthesia at Harlem Hospital, where she worked most of her career. Later, she was the director of the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing. In 1949, Brangman-Dumpson established the Harlem Hospital Nurse Anesthesia program and served as its director until her retirement in 1985. True to her vision of welcoming a diverse group of nurses to the anesthesia field, Brangman-Dumpson’s first class included an Irish Catholic student, a Jewish student with a doctoral degree, two students from Africa, a Filipino student, and a Korean student, with the rest being Caucasian, Hispanic, and Black students from New York and New Jersey.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was at a Harlem event for the launch of his first book, Stride Toward Freedom, when he was stabbed in the chest with a letter opener by a mentally ill woman on December 20, 1958. Rushed to Harlem Hospital in New York City, King was met by the doctors and anesthesia team – including nurse anesthetist Brangman-Dumpson – who would save his life. Brangman-Dumpson remained at Harlem Hospital for another 45 years after caring for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. It was there she served as director of the School of Anesthesia and received AANA’s Outstanding Educator Award. She is an author, activist, and role model to many.

Lillian Holland Harvey

Lillian Holland Harvey began her educational career with a nursing diploma from Lincoln Hospital School of Nursing in New York. She then received her Bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1944, a Master’s degree from Columbia University’s Teacher College in 1949, and a doctorate in education from Teacher’s College at Columbia University in 1966. Dr. Harvey served as director of nurse training at the Tuskegee School for Nurses starting in 1945 and became the dean in 1948. During her tenure, she transitioned the program to become the first to offer a Bachelor of Science degree in nursing in Alabama.

Dr. Harvey was a proponent of the integration of Black nurses into the workforce. She advocated for the full participation of Black nurses throughout Alabama, as seen in her desegregation efforts as the only Black nurse in the Alabama State Nurses’ Association. She served for 30 years as the Dean of the Tuskegee University School of Nursing where she was responsible for developing the school’s Bachelor of Science in Nursing Degree. She served as a leader to her students and inspired them to continue their education while giving back to the community. She received the Mary Mahoney Medal from the American Nurses Association in 1982 and was inducted into the Alabama Nursing Hall of Fame in 2001.

Eddie Bernice Johnson

Eddie Bernice Johnson was an American politician who represented Texas’s 30th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1993 to 2023, and she was a member of the Democratic Party. Johnson moved to Indiana to attend Saint Mary’s College of Notre Dame, where she graduated in 1955 with her nursing certificate. She transferred to Texas Christian University, from which she received a bachelor’s degree in nursing. She later attended Southern Methodist University and earned a Master of Public Administration in 1976. Johnson was the first Black woman to serve as Chief Psychiatric Nurse at the Dallas Veterans Administration Hospital.

She left the hospital in 1972 to run for public office in the Texas House of Representatives. There, she made a name for herself fighting for minority and women’s issues. In 1976, Johnson earned her M.P.A. degree from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, and in 1977, President Jimmy Carter appointed her as the principal official of Region VI for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (H.E.W.). In 1986, Johnson was elected to public office once again, but this time to the Texas Senate, where she worked tirelessly to improve health care and to end racial discrimination. In 1992, Johnson ran for the U.S. House of Representatives and was elected. As a U.S. Congresswoman, Johnson has led the battle on legislation to improve health care, the environment, civil rights, women’s issues, science research, and education.

Boitumelo Masihleho is a South African digital content creator. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Rhodes University in Journalism and Media Studies and Politics and International Studies.

She’s an experienced multimedia journalist who is committed to writing balanced, informative and interesting stories on a number of topics. Boitumelo has her own YouTube channel where she shares her love for affordable beauty and lifestyle content.