Wreckage of slave ship, Clotilda from Historic sketches of the South by Emma Langdon Roche, publisher: New York: The Knickerbocker Press, 1914. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1860, in the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa, as part of his annual dry-season raids for slaves, King Ghezo, the king of Dahomey, raided a town. What was his loot? Human beings.

Amongst his captives were 19-year-old Cudjo Lewis ( Oluale Kossola), 12-year-old Sally Smith (Redoshi), and 2-year-old Matilda McCrear (Abake), all from the Yoruba tribe.

They were taken to Ouidah Slave Port, where they were sold to buyers and slaveowners. For Cudjo, Sally, and Matilda, their buyers were Timothy Meaher, a businessman and Alabama slaveholder, and Clotilda’s captain, William Foster.

These two brought a total of 110 West Africans to Mobile, Alabama, where they sold some and personally enslaved the rest.

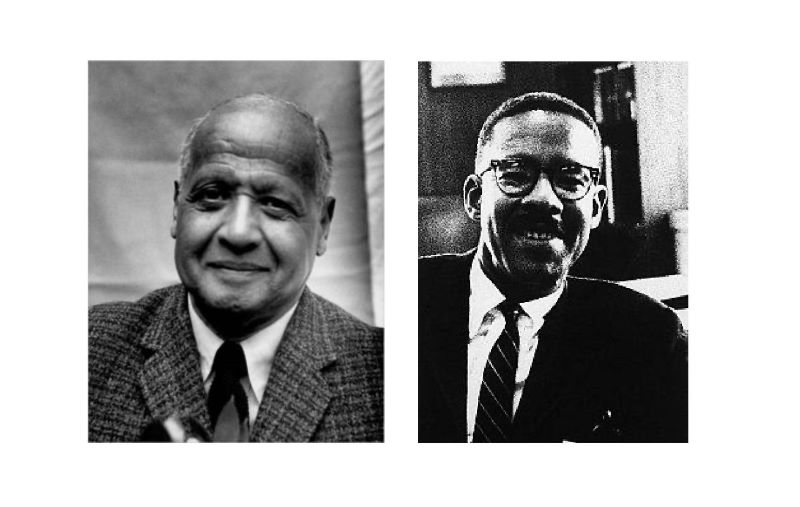

Oluale Kossola (Cudjo Lewis)

(Image by Bluesy Daye via Flickr)Cudjo Lewis was born Oluale Kossola in the present-day West African country of Benin. He was the second of four children and had a total of 12 step-siblings.

Like most young men, Cudjo fell in love with a young lady, and at his father’s urging, underwent an initiation that enabled young men and women to get married.

He was making plans when tragedy struck and his life was taken away from him. His town was raided, and Kossola, along with many others, was taken into captivity.

Their captors took them to Abomey Dahomey’s capital, and then to Ouidah.

Benin, West Africa, Ouidah, a memorial at the door of no return, a major slave port during the trans-Atlantic slave trade (Source: Wikipedia)

Benin, West Africa, Ouidah, a memorial at the door of no return, a major slave port during the trans-Atlantic slave trade (Source: Wikipedia)

They were held for 3 weeks in a slave pen known as a ‘Barracoon’ before being sent across the Atlantic together with other captives from Nigeria and Benin regions.

This journey was known during the slave trade as ‘the Middle Passage’.

During Kossola‘s 45 days on the ship, he suffered from terrible thirst and the humiliation of being forced to be on board naked.

Life as a Slave

After a long 6 week journey, Kossola and the other prisoners arrived in Mobile, Alabama.

Kossola was then enslaved by James Meaher, a wealthy ship captain and brother of Timothy Meaher: the man who had organized the expedition.

Since James was unable to pronounce Kossola’s name, the young man told his new owner to call him Cudjo, a name given by the Fon and Ewe peoples of West Africa to boys who are born on Monday.

During his five years of enslavement, Cudjo worked on a steamship and lived with his shipmates under Meaher’s house, which was built high above the ground.

In 1865, following the emancipation, Cujdo regained his freedom and took the name, Lewis. He then married Abile, a young woman who had also been on the Clotilda, and like their other companions, the couple’s objective was to return home. However, when they failed to raise enough money for the trip, they stayed in Alabama.

Because Timothy Meaher had been responsible for their ordeal, the former slaves decided to ask him for reparations in the form of free land. Cudjo was chosen as the spokesman, but Meaher response was:

“Fool do you think I goin’ give you property on top of property? I tookee good keer my slaves and derefo’ I doan owe dem nothin.”

They were left with no choice but to purchase land from him and others and establish African Town, which still exists today in Mobile, Alabama.

Cudjo worked as a shingle maker, but after being injured in a train accident in 1902 (for which he sued the railroad company), he became African Town’s church sexton.

Cudjo and Abile had five sons and one daughter, all of whom they gave American and Yoruba names. Sadly, all of the children died young.

Here is a list of Cudjo’s children and the circumstances that led to their deaths:

- Celia/Ebeossi died of illness at 15.

- Young Cudjo was killed by a Black deputy sheriff.

- David/Adeniah was hit by a train.

- Pollee/Dahoo disappeared and was probably killed.

- James/Ahnonotoe died of illness.

- Aleck/Iyadjemi died of illness.

Abile passed away in 1908, just one month before Aleck died. Cudjo again suffered the loss of his family.

During the last years of his life, he achieved some fame when writers and journalists interviewed him and made his story known to the public. However, his interview with Alabama-born author Zora Neale Hurston gained more popularity.

Zora’s book based on Cudjo’s account can be found on Amazon. During the interview, amidst tears, Kossola tells Hurston,

“Cudjo feel so lonely, he can’t help he cry sometime.”

Matilda McCrear (Abake)

Matilda was only 2 years old when she arrived in Mobile, Alabama as a captive of the infamous Clotilda ship.

Abake (Matilda’s original name) arrived in Alabama with her mother, Gracie, her three older sisters, and a man who would later become their stepfather.

(Gracie was forced into marriage by her white owners)

According to Eva Berry, Matilda’s granddaughter, who was 12 years when her mother died, said her grandmother was too young to remember the horrible experience of the 6 weeks crossing, but Gracie told her daughter terrifying stories of the hellish experience they passed through in Clotilda and how people, especially children, lost their lives, including Gracie’s nephew.

Eva remembers her grandmother as a dark-skinned woman with long hair.

Just like Cudjo, their journey to America began when their kingdom was raided, her father killed, being taken into captivity and sold to William Foster and Timothy Meaher.

When they arrived in Alabama, Matilda,, Rodeshi, and their mother, Gracie, were sold to Memorable Walker Creagh, a planter, physician, and state representative, while her two eldest sisters were sold to another buyer’s family. They never saw them again.

Gracie, Matilda, and Rodeshi made an attempt to run away by hiding in a swamp for several hours, only to be discovered by the overseer’s dogs.

In 1865, after the emancipation proclamation, Matilda left the Creagh plantation for Athens, Alabama, where she had three mixed-race kids. The circumstances surrounding the birth of the three children are quite unknown.

It is believed the pregnancy may have been conceived by rape since cases of sexual assault of Black women were not rare.

In 1879, she moved again, this time to Martin Station, Alabama with her children. There she met and began a relationship with Jacob Schuler, a German immigrant. They were together for 17 years. Jacob Schuler was a constable, deputy sheriff, and overseer.

These two never got married to each other or to any other person. It was impossible at that time. They lived close to each other and went on to have 7 kids together.

Matilda still has known living descendants.

She died in 1940 at the age of 82.

Rodeshi (Sally Smith)

(Image Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Rodeshi (Sally Smith) is the older sister of Matilda McCrear. She was kidnapped alongside her sisters and mother.

After Memorable Walker Creagh bought Matilda and her mother Gracie, Rodeshi was forced to become a child bride before being sold again, this time around to Washington Smith, owner of the Bogue Chitto plantation near Selma, and also the co-founder of the Bank of Selma.

The two Dahomey people who had kidnapped Redoshi and her family members were also taken captive and transported to North America on the same slave ship, and they worked alongside Rodeshi in the fields.

Just like her mother, Redoshi was forced into marriage with another captive, who was already married and spoke a different language. They had children together.

Unlike Matilda, Redoshi did not leave the plantation where she was enslaved.

Washington Smith died in 1869 but his wife continued to run the plantation together with advanced merchants. They controlled the finances of the sharecroppers and settled annual accounts to their benefit, leaving Rodeshi and her husband Yawith in poverty.

Even after her husband’s death, Rodeshi continued to live with her daughter in the estate where she was enslaved. Little is known if she later left the Bogue Chitto estate or if had any other children.

She adopted Christianity, practiced her religious traditions, and taught them to her daughter.

Her daughter had many name variants: Leasy, Luth A, Lethe, Lewis, and Lethy. She had children of her own.

Further Readings

In his journal, Captain William Foster of the Clotilda described how he came in possession of McCrear and other enslaved Africans in his ship.

“From thence I went to see the King of Dahomey. Having agreeably transacted affairs with the Prince we went to the warehouse where they had in confinement four thousand captives in a state of nudity from which they gave me liberty to select one hundred and twenty-five as mine offering to brand them for me, from which I peremptorily forbid; commenced taking on cargo of negroes, successfully securing on board one hundred and ten.”

Captain William Foster account of the Clotilda ship and his notes can be found in Mobile Public Library Digital Archives.

Efforts Of Reconciliation

In an interview for National Geographic’s February 2020 cover story, Timothy Meaher’s great-grandson Robert Meaher questioned whether the Clotilda’s wreckage is real. He emphasized that Timothy never went to prison for his slave-trading crimes (many white men didn’t) and tried to justify the crimes by saying that Cudjo Lewis became a Christian in the U.S. He also said he is not open to meeting with the ship’s survivors.

Tax records show the family still owns millions of dollars worth of land around Mobile, Alabama.

Clotilda Ship Found

To hide evidence, Foster burned the Clotilda and sank it in the sea. However, after it was found, it was discovered that two-thirds of the ship did not burn.

In 2017, a search for the Clotilda based on conversations with the descendants of the founders of Africa Town began. One year later, in 2018, it seemed that Ben Raines, a reporter with AL.com, had found the Clotilda, but that wreck turned out to be too large to be the missing ship.

But on May 22nd, 2019, researchers confirmed that the remains of the vessel were found along the Mobile River, near 12 Mile Island, and just north of the Mobile Bay-Delta.

According to maritime archaeologist James Delgado of the Florida-based SEARCH Inc.,

“It’s the most intact (slave-ship) wreck ever discovered,”

“It’s because it’s sitting in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta with fresh water and in mud that protected it that it’s still there.”

At least two-thirds of the ship remains, and the existence of the unlit and unventilated slave pen, built during the voyage by the addition of a bulkhead, where people were held as cargo below the main deck for weeks, raises questions about whether food and water containers, chains, and even human DNA could remain in the hull, said Delgado.

The authentication and confirmation of the Clotilda were led by the Alabama Historical Commission and SEARCH Inc., a group of maritime archaeologists and divers who specialize in historic shipwrecks.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture’s Slave Wrecks Project (SWP) joined the effort to help involve the community of Africatown in the preservation of the history, explains Smithsonian curator and SWP co-director Paul Gardullo.

The photos of the remains of the Clotilda ship can be found here.

What are your thoughts on this?

Drop a comment below.

For more on the history of Transatlantic Slavery, subscribe and follow our social media platforms.

Works Cited

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/last-slave-ship-survivor-descendants-identified

https://www.history.com/news/zora-neale-hurston-barracoon-slave-clotilda-survivor

https://from.ncl.ac.uk/the-last-two-transatlantic-slave-trade-survivors

https://www.ncl.ac.uk/press/articles/archive/2020/03/matildamccrear

http://encyclopediaofalabama.org/

https://www.npr.org/2021/12/22/1067078342/wreckage-of-last-slave-ship-clotilda-alabama

Jessica Uchechi Nwanguma is a Writer, Content and Social Media Strategist. She has a degree in Dental Technology and several certifications and has taken courses on Writing, SEO and digital and content marketing. Her book ‘Beyond Agadez: the untold stories of the victims of human trafficking and organised crime.’

is available on Amazon Kindle. She can be found online on Candour.substack.com.