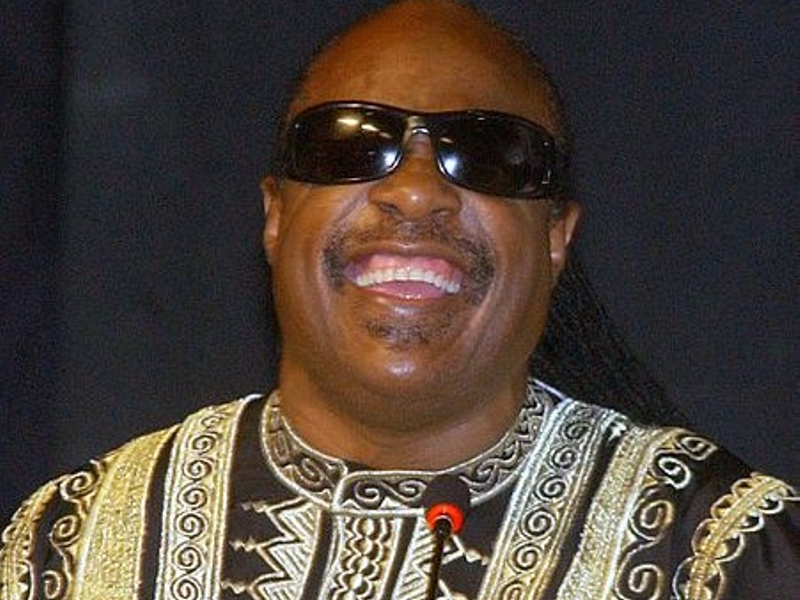

Stevie Wonder. Photo by Antonio Cruz/ABr, CC BY 3.0 BR, via Wikimedia Commons

There’s a long history of African Americans settling in Ghana or keeping in close contact with the first African country to gain independence. This relationship has most recently been exemplified by musician Stevie Wonder taking up Ghanaian citizenship.

Ghana, which gained independence in 1957, became a beacon for African Americans disenchanted with their country’s racial problems. Ghana’s first prime minister, the pan-Africanist Kwame Nkrumah, was notable for forging links between Africans on the continent and those in the African diaspora.

Escaping segregation, discrimination, and other forms of marginalization and racial injustice, African Americans looked to Africa. Others excited by the change brought by decolonization saw a chance to contribute to the land of their ancestors. There has been a spike in interest in Ghana recently, with some reports indicating that around 1,500 have relocated there since 2019.

Part of my work as a professor of history has been to study the relationship between African Americans and the African continent. My book, African Americans and Africa: A New History, explores these long-standing links and a shared past that for many lives today.

In this article, I explain how these feelings have been rekindled and are pushing African Americans toward the continent once again. Enslaved Africans brought as captives to the United States, beginning in the 17th century, brought with them a part of their “Africa”. Many manifestations of “African American culture” still retain this connection.

From the moment women and men were forcibly taken from the continent, their homelands remained in their hearts, memories, cuisines, religious practices, cultural elements, music, dance, and all the things they took with them. These were passed on to subsequent generations. Although over the centuries much was transformed and lost, Africa came to have a place in the consciousness of Black Americans. Through the years of struggles and triumphs, as they became fully-fledged American citizens, their gaze never left the land from which their ancestors were taken.

In varying degrees, they engaged with the continent as missionaries, teachers, and champions of African development. Black Americans Paul Robeson and Alphaeus Hunton spoke out in support of African freedom and decolonization, the anti-apartheid struggle, and other political movements. Hunton spent some years in Ghana in the 1960s and died in Zambia. In the 1980s there was an Afrocentric movement of sorts that filtered into popular culture. The late 1980s and early 1990s was an era of “Afrocentric rap”.

Some music artists celebrated Black culture, representing Africa positively, even if in romantic ways. As the sociologist Erica Hill-Yates notes, the lyrics exemplified a “desire not only to acknowledge but also to honor Africa as a vital force in the making of Black people throughout the diaspora.”

While much of this exemplified an imagined vision of Africa, it showed a desire for connection. This was also the era of the anti-apartheid movement, and African Americans were at the forefront of lobbying the US government for the release of South Africa’s then-imprisoned freedom fighter, Nelson Mandela.

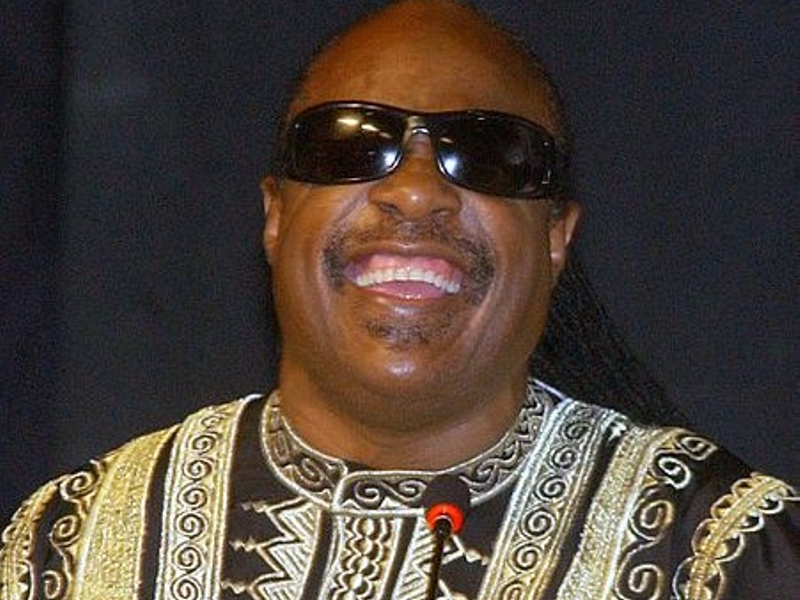

Stevie Wonder performing. Photo by Pete Souza, official White House photographer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Stevie Wonder was a voice for many of these happenings. He is one of many Black Americans to understand that although the bonds of kinship between African Americans and Africa have been bent and broken in different ways over the centuries, it is always possible to repair them for those who choose to do so.

As early as the 1950s and 1960s a small group of Black Americans made Ghana their home. Some, like US writer Maya Angelou and civil rights activist Pauli Murray, eventually returned to America. But many, like Robert Lee, who with his wife Sara was among the first dentists in Ghana, and Lou Gardner, a plumber, made their homes there permanently, contributing to the development of the new nation.

Arguably the most famous African American, W.E.B. Dubois, was laid to rest in Ghana in 1963. Dubois had a long relationship with Africa, writing about its history and championing the continent and its people.

In his 1940 bookDusk of Dawn, he wrote:

Since the fifteenth century, these ancestors of mine and their other descendants have had a common history … the real essence of this kinship is its social heritage of slavery; discrimination, and insult … It is this unity that draws me to Africa.

Stevie Wonder’s long relationship with Ghana exemplifies this. In explaining his decision to take up Ghanaian citizenship, he spoke about the culmination of a 50-year dream of “uniting people of African descent and the diaspora”.

He has said:

My message is, people, let’s come together for the goodness of our culture, and the goodness of all cultures, and the goodness of the world.

Stevie Wonder’s desire for African citizenship took root during his tour of the continent in the 1970s. He has always been a champion for African issues. He wrote a song, It’s Wrong (Apartheid), against apartheid that was banned in South Africa for many years.

As African Americans continue to fight for full acceptance and equality in a country with persistent racial divisions, their links to Africa will surely continue.