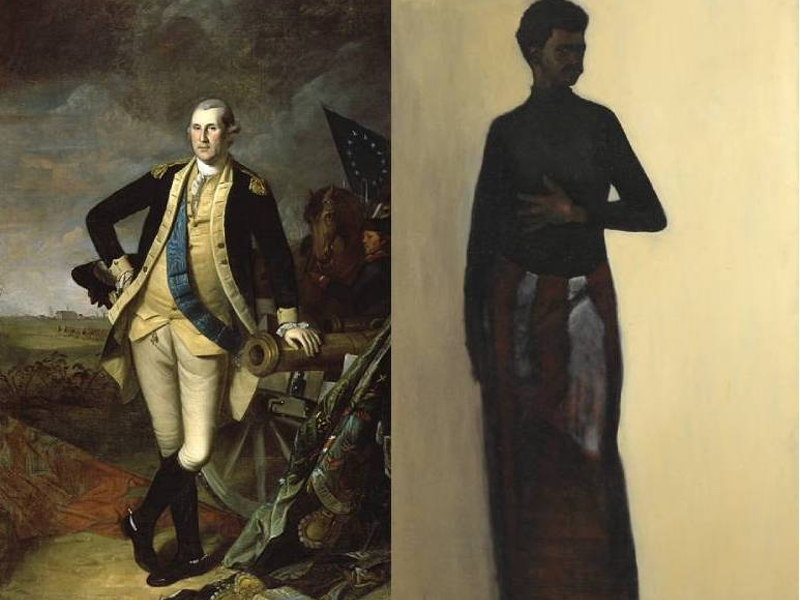

In Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) founded in 1805, has unveiled a 103-piece exhibition entitled, Making American Artists. It presents PAFA’s collection of well-known historic art from 1776 to 1976 alongside “traditionally underrepresented artists.” In the exhibition, the pairing of Charles Willson Peales’s George Washington at Princeton (1779) with James Brantley’s Brother James (1968) is one of the exhibition’s efforts to question what it meant to be an American artist when PAFA was founded and what it meant to be an American artist by the late twentieth century.

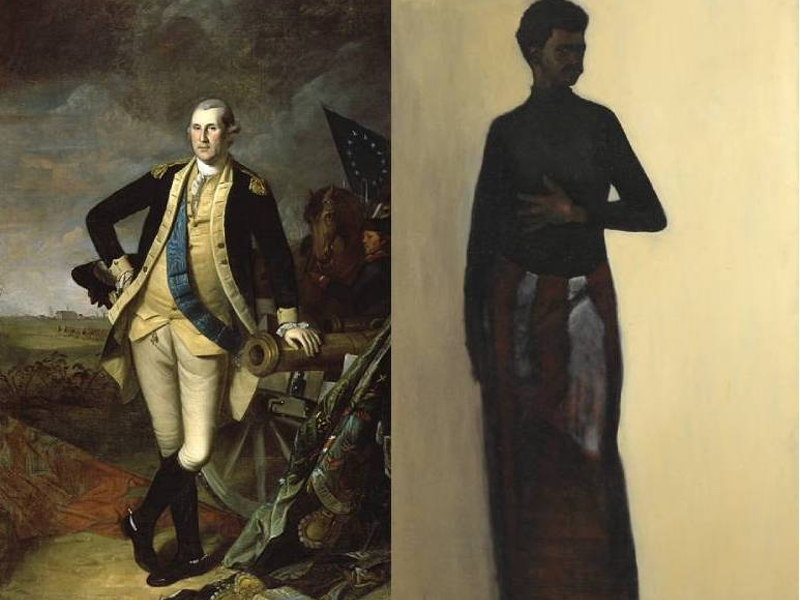

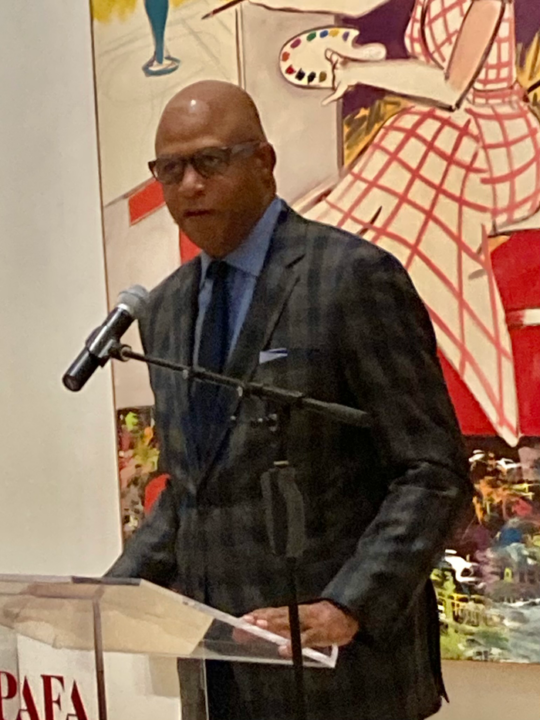

PAFA President and CEO Eric Pryor says “Making American Artists is an epic collection of American art, featuring some of our most famous images and artists in new conversations with each other.” Pryor, the former president of the Harlem School of the Arts, is the first African American to head up PAFA since its founding. in 1805. Pryor is described as strategic, creative and a collaborative leader with over 25 years of experience in education, museum administration and community building.

But, in the aftermath of the on-camera police killing of George Floyd that triggered sometimes violent protests in cities across the nation, government, corporations and institutions, including arts institutions such as PAFA have come face to face with the recognition that no longer can they ignore systemic racism, injustice and exclusion. The question being posed is, are you part of the problem or part of the solution?

Enter the nomenclature – Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI). It is defined as a term used to describe policies and programs that promote the representation and participation of different groups of individuals, including different ages, races, genders, religions, cultures and sexual orientations. Admittedly, that’s a lot for these entities to wrap their arms around. But, hopefully this time of “awokeness” will be more than a moment.

Arts institutions and cultural spaces are among those incorporating DEI mandates as part of their mission. But DEI has to be more than a well-crafted press release or the insertion of Black, Brown and LGBTQ props. Hopefully, DEI’s efforts will reach, affect and benefit the masses of overlooked and underrepresented folk. And, art lovers or those trying to better understand and appreciate what is termed art will check out the PAFA exhibition.

PAFA President Eric Pryor

There are only 11 works by Black artists in the exhibition and a sculpture by world celebrated painter Henry Ossawa Tanner of his father, AME Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner which is the highlight of the exhibition. Henry O.Tanner enrolled at PAFA in 1880 before settling and achieving fame in Paris. The sculpture was a gift of Leslie Tanner Moore and the Tanner family to PAFA.

The exhibition also includes a self-portrait of Dox Thrash, a prolific and pioneering printmaker who lived in Philadelphia in the 1920s. He became the first African American artist to work for the Fine Print Workshop of Philadelphia that was a branch of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). His imagery captured his life in the south as well as the segregated community he lived in in Philadelphia.

There was a Dox Thrash mural located near 17th and Girard Avenue in North Philadelphia, but it became partially blocked from view because of construction of an adjoining apartment building. The mural was erased earlier this year.

Also, Ghanaian sculptor, textile designer and musician Saka Acquaye is recognized in the exhibition, but in an easy to be missed location. Acquaye attended PAFA from 1953 -1956. While in Philadelphia he founded the West African Cultural Society, an African dance company that included Arthur Hall, the founder of the Afro American Dance Ensemble and the Ile Ife Black Humanitarian Center. He died in Ghana in 2007 and was celebrated as a “pioneer to the pioneers of contemporary art in Ghana.”

President Pryor, who received an MFA degree from Temple’s Tyler School of Art, says, “This exhibition explores PAFA’s impressive collection with a critical eye and emphasizes its transformative contribution to the history of American art.” Pryor has been at PAFA for less than a year and he has demonstrated his community roots that buttress his academic and administrative resume. So maybe, just maybe, going forward PAFA will have that “new” conversation with those who for too long have been overlooked and underrepresented within its historic walls.

Karen Warrington has had a decades long career as a broadcast journalist, communications professional, performing artist, and documentary filmmaker. She has traveled extensively throughout Africa, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia. She is committed to being a voice for the African Diaspora.