( Monrovia, Liberia. Image by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid via Flickr https://www.flickr.com/photos/chathamhouse/6011337236 )

“If you want to know the end, look at the beginning” -African proverb

Displacement, complex identities and the quest for ‘home’ are remnants of the TransAtlantic Slave Trade that the descendants of the enslaved continue to grapple with. In countries settled by formerly enslaved communities like Liberia, Sierra Leone and Haiti, political ideologies, journeys towards liberty, and advancement are both blessed and burdened by innovation, and marred by neo-colonial ideologies.

In celebration of Liberia’s bicentennial, we are exploring economic, social and political relations between the US and formerly-enslaved societies, with a special focus on Liberia, Sierra Leone, Jamaica, Haiti and more.

In Part I of ‘Examining Relations Between the US and Formerly Enslaved Nations’, we delve into the motivations and impacts of former slaves’ repatriation to Liberia, and traverse two centuries of international relations between the United States and Liberia, including infrastructure-building and aid initiatives, allyship and the manifestations of relationships cultivated between indigenous Liberians and repatriated ex-slaves.

( ‘Remarks on the Colony of Liberia and the American Colonization Society’, written by Bermudan-Canadian abolitionist Charles Stuart in 1832. Image by BiblioArchives/LibraryArchives via Flickr )

( ‘Remarks on the Colony of Liberia and the American Colonization Society’, written by Bermudan-Canadian abolitionist Charles Stuart in 1832. Image by BiblioArchives/LibraryArchives via Flickr )

The Creation of Liberia as a Haven for Formerly Enslaved Blacks

Liberia is a West African country with a blended culture, composed of indigenous African tribes like the Gola, Kissi, Kru, and Mande, and Americo-Liberians or Congoes, who are descendents of formerly enslaved populations from the United States and the Caribbean. This year, Liberia celebrates its bicentennial, given that the first formerly enslaved repatriates arrived in Liberia in 1822. US-Liberia relations, since the inception of the country as a “colony”, reflects American consciousness, the guise of democracy, exclusion, and indigenous-settler tension.

The American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded in 1817 by Robert Finley, Henry Clay, Bushrod Washington (nephew of George Washington) and Francis Scott Key, to strategically extradite emancipated Black populations, at a time when the emergence of formerly enslaved Black communities threatened America’s system of slavery.

Other factors that led to the founding of the ACS include Africans illegally trafficked to the US after the abolishment of the slave trade, the rise of anti-slavery ideologies, slave rebellions and diasporic groups of freed Blacks in America. The ACS was composed of both slave-supporters and abolitionists.

( Americo-Liberians. Image by Wikiaddict8962 via Wikimedia Commons )

( Americo-Liberians. Image by Wikiaddict8962 via Wikimedia Commons )

In 1820, the first group of freed Blacks were sent to Sherbro Island, Sierra Leone, with ACS representatives. During that time, Britain established a colony for freed Blacks, Sierra Leone, and had begun sending formerly enslaved populations there. However, the living conditions in Sherbro Island were unfavorable, so the ACS sought an alternative location. Cape Mesurado, an area on the coast of Liberia, was allotted for the ACS for repatriation as a “colony” in 1821.

By 1867, the ACS sent more than 13,000 freed Blacks to Liberia, who mostly settled on the coastal lands. In the 1890s, the ACS focused on developing the “colony”, including incorporating formal education and self-sustaining systems, for the natives. The Booker T. Washington Institute, for example, was founded in 1929. Miss Georgia E.L. Patton, MD, a formerly enslaved woman from Tennessee who moved to Liberia between 1890 and 1900, noted in a letter that she sought to practice medicine in the “colony”.

(Liberian women attend math and literacy class. Image by United Nations Photo via Flickr )

(Liberian women attend math and literacy class. Image by United Nations Photo via Flickr )

Indigenous-Expat Tension, and Social, Political and Economic Inequality

Indigenous Liberians faced discrimination at the hands of this new system. Helen Nah Sammie, Publisher of the Community Voices Newspaper in Liberia, gives insight into the relationships between Americo-Liberians and indigenous Liberians:

“During those days, (indigenous) people had to change their names to get education. Now things are changing. You will hear native names and people want to know the meaning of that. I want to know whether we talk about reconciliation, because I see the country as really divided. People look at the Americo-Liberians and how they brought that aggression. They had aggression in them (perhaps) because of how they were treated in America, and they brought that aggression back to the people in Liberia. It’s a big process that we have to talk about, because that is why the country can not get to the level that people want it to be.”

( Indigenous Liberian chiefs of the Krahn tribe, between 1900-1940. Image by Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen via Wikimedia Commons )

( Indigenous Liberian chiefs of the Krahn tribe, between 1900-1940. Image by Collectie Stichting Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen via Wikimedia Commons )

It is rumored that after the first ACS group landed in Liberia and left Sherbro Island, ACS members forced a local chief to sell land to them at gunpoint. In a twisted turn of events, freed expatriates became plantation owners and overseers, with indigenous Liberians working in plantations similar to the conditions of the enslaved in America, with little pay. Indigenous groups revolted against the Americo-Liberians, but with the support of the US, Americo-Liberians were able to establish themselves in the land.

Siatta Johnson, President of the Female Journalist Association of Liberia, says: “A lot of the settlers still had their roots in the US and they still do today. So, in my opinion, they weren’t seeing Liberia as a home to stay in, they were seeing Liberia as a farm. It put a deep dent in the infrastructure and economy of Liberia. Before the civil crisis, Liberians with lots of money were not investing or banking in the country. They were not keeping their resources in Liberia, which is a debatable topic. We know there are lots of positives and negatives.”

Jehudi Ashmun, a politician and representative of the ACS, designed the Liberian legislative system akin to the United States political system, and African-American repatriates were placed in political positions.

( Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a free, Virginia born mixed race settler became the first President of Liberia. Image by Story Liberia via Wikimedia Commons )

American ideals of democracy were weaved into Liberia’s political system. When Liberia gained independence in 1847, the country was governed by Americo-Liberians. Native Liberians were excluded from the political process, as they were required to legally own a specific amount of land and money to vote. Indigenous Liberians were granted citizenship in 1904, however, they were denied the right to vote until 1946. The True Whig Party, a political party that dominated Liberian politics until 1980, was almost exclusively Americo-Liberian or Americo-Liberian descended.

Throughout this time, Liberia continued to rely on financial assistance from the ACS and the United States. In 1926, the Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, an American corporation, opened a rubber plantation in Liberia, and the US, and the elites of Liberia were the main benefactors. Between 1940 and 1946, the US Forces established a base in Liberia.

Christiana Jimmy or Winnie Saywah Jimmy, Liberian journalist and Acting Managing Editor of the Inquirer Newspaper of Liberia, says: “The US-Liberia relationship dates back to 1819. When we talk about emancipation, and bring it back to Liberia, it is hard to explain. It’s hard to find that freedom because it starts with the settling of the slaves. Ownership continued to drive our political system. The struggle of equality and who owns Liberia is all interchangeable. We still struggle with that today. If we look at Liberia and how it came to be a nation, it was by indirect supervision. Some individuals still struggle to have ownership. Because of that, we cannot define freedom. If you look at the economy now it is strained, and because of that, freedom cannot be useful or flexible for us.”

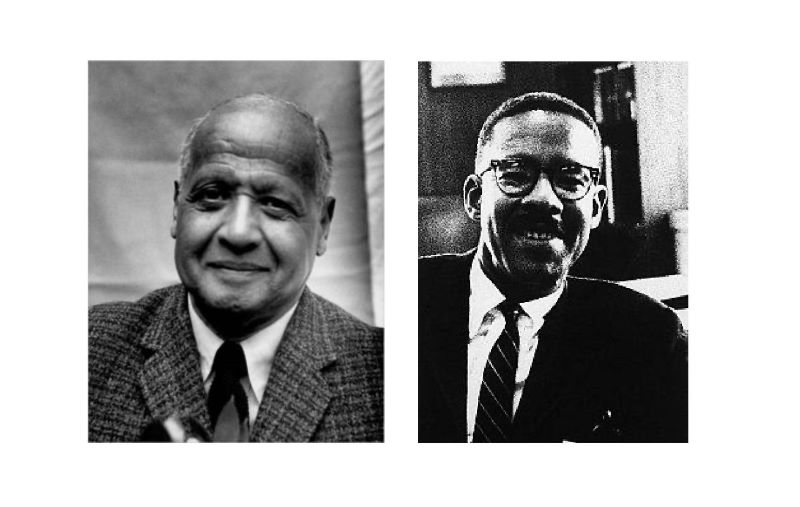

( John Russworm, a Jamaican-born, mixed race abolitionist settled in Liberia. Image by Cliff from Arlington, Virginia via Wikimedia Commons )

Continued Marginalization, the First Indigenous Rule, and the Liberian First and Second Civil War

The marginalization of native Liberians continued for over 150 years, and although some Americo-Liberian or Americo-Liberian mixed presidents focused on reform for indigenous groups, change was slow and the indigenes continued to experience economic lack while Americo-Liberians flourished. This divide led to a violent coup d’etat in 1980, spearheaded by Krahn sargent Samuel K. Doe, and led to the murder of Americo-Liberian president William Tolbert. Doe became the first indigenous Liberian to be president, and was supported by the US after the coup.

Doe’s rule of the country was marked by corruption, ethnic violence, political persecution, and economic mismanagement. Due to international backlash, Doe was influenced to lead an election, which he won in 1985. The elections were said to have been rigged, and Doe’s mismanagement and favoritism of his ethnic group, the Krahn, continued.

The same year the Cold War ended, in 1989, Liberian politician Charles Taylor and his army of rebels (the National Patriotic Front of Liberia or NPFL), stormed Liberia and catalyzed a Civil War. Despite the centuries long allyship, the US did not intervene in this seven-year long war, in which an estimated 30,000 people were killed, and half of the population displaced. Prince Johnson, a Liberian politician and former rebel leader of the Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL) in Liberia’s first civil war, executed Doe and broadcasted it on TV. Johnson is currently a senator in Liberia.

( Prince Johnson, Liberian politician and rebel leader in Liberia’s First Civil War. Image by Travis Lupick via Flickr )

In 1996, when the first civil war ended, Charles Taylor became the president of Liberia. However, peace was short-lived, as a second Liberian Civil War erupted in 1999, when Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy (LURD), a guerrilla group, supported by Guinea, laid siege on the country.

In 2003, near the end of the second civil war, 200 American soldiers arrived in support of ECOWAS efforts to broker peace in Liberia. In 2005, Madam Ellen Johnson Sirleaf became the president of Liberia, and first African female president.

Lessons for Expat Migration: Streamlining Indigenous Systems into Modern Politics and Integration vs Domination

The prolonged disenfranchisement of indigenous groups, including the political, economic and social inequality that erupted in a 1980 coup, and led to the First Liberian Civil War, illustrates a fragile ecosystem built on inequality, and the dangers of unequal access to education and development. US-Liberia relations implemented a colonial-like system that did not integrate ex-slaves into the existing political systems that were in operation among indigenous tribes, but rather sought to dominate and exert authority, power and ownership in the land.

This system proved toxic, as the coup d’etat resulted in Liberian indigenes supporting Samuel Doe, who may not have been equipped to run a country using a western system. Political, social and economic infrastructure that focused on collaboration and integration rather than domination may have created a more even playing field for all of the inhabitants of Liberia.

( HE Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Image by Chatham House via Flickr )

What does an African-based political system look like for Liberia, and how would it function in international relations and political dealings with countries like the United States?

Bai Best, the Managing Director of the Daily Observer in Liberia, is a descendant of settlers from the West Indies, one from Barbados and the other from Trinidad. He says his family adopted the language of the Pele people. In discussing past and contemporary interethnic relations, Bai says “There were always disagreements about settlers vs natives, and here we are today. Today, there has been so much intermarriages and so much of a melting pot situation that no one can really say I’m this or that because so many have blended their heritage. Going forward, decolonization should be centered around how we go about celebrating the real culture of Liberia. We do have a culture but it’s not being practiced.

The Ghanaians and Sierra Leoneans have a template. They have taken that template and transposed their colonized part with their native heritage. In Liberia, we tried to do that, and if we go back as far as the 50’s or 60’s, we have records of how our people used to live and the traditions that held our communities together. When people started to send their children abroad to England and the United States, that became their identity, whereas there are other people who remained here and whatever they met here from birth became their identity.”

Bai stresses the importance of incorporating indigenous Liberian values into Liberia’s infrastructure: “That goes back to having us reintroduce our heritage into schools, as low as the elementary level all the way to the college level. We need to have more Liberian scholars, in terms of the practice of Liberia. We need more technocrats, scholarships and people who have a fairly broad understanding of Liberia’s history, culture and society. They are few and far (in) between now, and most of them are dying out. There’s a lot of work to be done.”

Stay tuned for Part II of ‘US-Liberia Relations’, where we discuss Liberian and Sierra Leonean expatriate communities who are rebuilding in the United States after surviving civil wars.

Works Cited

http://slaveryandremembrance.org/people/person/?id=PP048

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/freed-u-s-slaves-depart-on-journey-to-africa

https://www.britannica.com/place/Liberia/History

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Firestone-Tire-and-Rubber-Company

https://www.loc.gov/item/2017700539

https://www.refworld.org/docid/4954ce5823.html

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/globalconnections/liberia/essays/uspolicy

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-Ghankay-Taylor

Nana Ama Addo is a writer, multimedia strategist, film director, and storytelling artist. She graduated with a BA in Africana Studies from the College of Wooster, and has studied at the University of Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Nana Ama tells stories of entrepreneurship and Ghana repatriation at her brand, Asiedua’s Imprint ( www.asieduasimprint.com ).