‘Examining Relations Between the US and Formerly Enslaved Nations’ is a 3-part series that explores economic, social and political relations between the United States and formerly-enslaved societies, with a special focus on Liberia, Sierra Leone, Jamaica and Haiti.

In part III of the series, we explore relations between the US and the Afro-Caribbean nations of Jamaica and Haiti, including Marcus Garvey’s Back to Africa movement, Haitian Migration to the US during and after the Haitian Revolution, the US occupation of Haiti, and, subsequently, raise a case for reparations.

A Brief Overview

The impact of US-Afro-Caribbean relations is ongoing and multifaceted. In 2019, Pew Charitable Trusts reported that of 88% of the Black foreign-born population in the US, 46% were from the Caribbean. In 2017, the US Department of the Caribbean reported that 95% of Caribbean immigrants in the United States came from the Afro-Caribbean countries of Jamaica, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Trinidad and Tobago and Cuba.

The contributions of Afro-Caribbean migrants and their offspring are great, with the imprint of individuals like the late Cicely Tyson, Colin Powell, Stokely Carmichael, Harry Belafonte James Weldon Johnson, Kamala Harris, Neile deGrasse Tyson, Alphonso Arturo Schomberg and more weaved into the country’s legacy.

Although the identity of some African and Afro-Caribbean immigrants gradually blend in with the general African-American population, their history is unique, and not to be ignored. Let’s explore the legacy of Haitian and Jamaican experiences with the US, including political movements, migration, occupation and international relations.

Marcus Garvey and the Back to Africa Movement

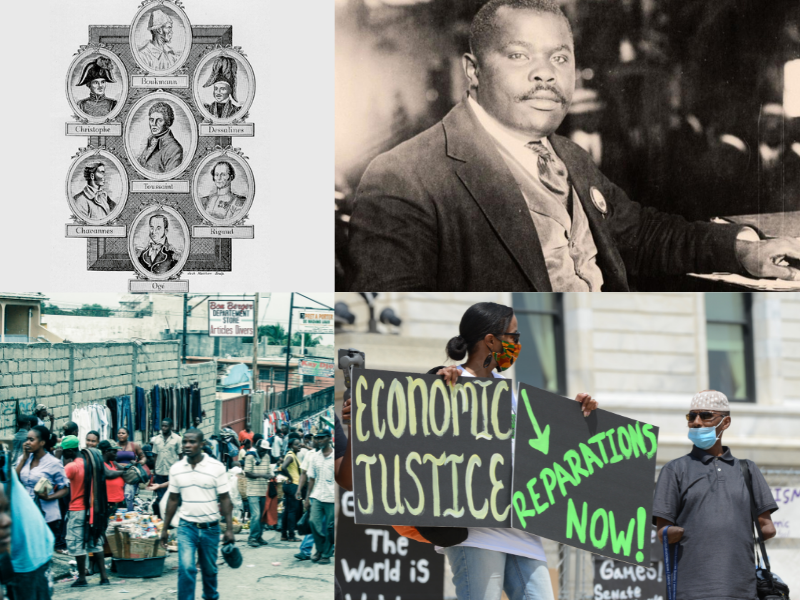

( Marcus Garvey. Image by Shahar1993 via Wikimedia Commons )

( Marcus Garvey. Image by Shahar1993 via Wikimedia Commons )

Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born activist, public speaker and businessman, was a monumental Pan-African leader. After experiencing race-based discrimination in the Jamaican school system, and his travels in the United Kingdom, Central and South America and the United States, Garvey became acquainted with issues that affected Black and working-class communities globally, and these experiences informed his activism.

Garvey created a Black-nationalist movement, and in 1914 he founded the United Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL), where he mobilized like-minded individuals through membership and multiple business initiatives that campaigned for Black economic empowerment, Black dignity and for descendents of Africa to return to the African continent.

( A Black Star Line stock paper signed by Marcus Garvey. Image by Rblack131 via Wikimedia Commons )

The Black Star Line, designed to provide entrepreneurship and trade-generation resources for the global African Diaspora, sailed to Cuba, Panama, Jamaica and other Caribbean countries. Garvey’s goal of repatriating Blacks to Liberia through the Black Star Line was never actualized, however, Garvey’s FBI investigation, coupled with his indictment for mail fraud, resulted in his deportation from the United States.

Today, the UNIA continues to seek change in their communities, with a 2020 estimate of 1,000 chapters in 40 countries, and operating branches in cities like Philadelphia.

US and Haiti Relations: Migration During and After the Haitian Revolution, the Creation and Impact of New Orleans Creolization and Prince Saunders

( The Haitian Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase. Image by elycefeliz via Flickr )

From approximately 1682 to 1763, and 1800 to 1803, France owned Louisiana as a territory and brought in slaves from its colonial islands, including Saint Domingue. The Haitian Revolution, which occurred in 1791, concerned slave owners around the globe, including those in America, who feared their enslaved populations would be inspired to revolt.

During this time, Afro-Haitians who migrated to states like Louisiana, and Philadelphia (which guaranteed enslaved people would be freed after six months of arriving), during and after the Haitian Revolution, were the subject of much scrutiny, as they were feared to lead slave rebellions that threatened the institution of slavery in the US. An estimated 900 Black Haitians arrived in Philadelphia during the Haitian Revolution, some being enslaved and others free Blacks or mulattos. The rising antislavery policies in Philadelphia were paradoxical to the French ideologies of slavery, but as many Black Philadelphians were free at the time, some Afro-Haitian migrants were able to be emancipated quickly, and even develop economic mobility, while others were forced to be enslaved for at least 7 years or forcibly migrated to other slave states. Enslaved Haitians resisted the institution of slavery in Philadelphia, with some running away and others retaliating against the French slaveowners.

( A Creole Cottage in Louisiana, built around 1810. Image by Jimmy Emerson, DVM via Flickr )

( A Creole Cottage in Louisiana, built around 1810. Image by Jimmy Emerson, DVM via Flickr )

Afro-Caribbeans from French colonies who migrated to Louisiana, including Haitians, formed a multifaceted society in New Orleans, and mixed with the other migrants in the area, developing a unique creole culture that is renowned even until today.

From 1791 to 1803, an estimated 1300 Haitians arrived in Louisiana. Haitian immigrants and other French Afro-Caribbeans in Louisiana also played a pivotal role in the Battle of New Orleans, which was fought against the British in 1813. However, the demographic remained repressed and antagonized politically, as the institution of slavery was rampant, and their rights to freedom were stifled.

Because of the conflicting interests of slavery, the US did not formally recognize Haiti as an independent nation until 1862, though the country supported Toussaint L’ouverture during a time of his rule.

Prince Saunders, the Connecticut-born scholar, is notable for his repatriation and contributions to Haiti. In 1816, Saunders traveled to Haiti and developed educational institutions for Black Haitian populations, during a time when the intellectual capacity of Blacks on the island was undermined. Saunders moved to Haiti permanently after being disillusioned with racism in the US, where he lived until his death in 1839.

US Occupation of Haiti

( Port Au-Prince, Haiti, 2012. Image by Alex Proimos via Wikimedia Commons )

( Port Au-Prince, Haiti, 2012. Image by Alex Proimos via Wikimedia Commons )

The US has occupied at least 80 countries, including the Afro-Caribbean countries of Cuba (Guantanamo Bay), Panama, Puerto Rico, Grenada and the Dominican Republic. From 1915 to 1934, the United States occupied Haiti, which was said to aim to develop political and economic stability in the country. The US had been considering annexing the island, including the Dominican Republic, since 1868. It was not until 1914 that the United States began military presence in Haiti, with $500,000 of Haitian funds sent to the United States bank. The US occupation of Haiti was accompanied by a political coalition between the US and Haiti, known as Gendarmerie. After multiple political endeavors, including placing a Haitian president in power, and race-based segregation and freedom of speech limiting policies, the US continued to orchestrate Haiti’s political sphere. Prolonged Haitian uprisings, unrest and economic disparity forced the US to withdraw from occupation in 1934.

A Case for Reparations

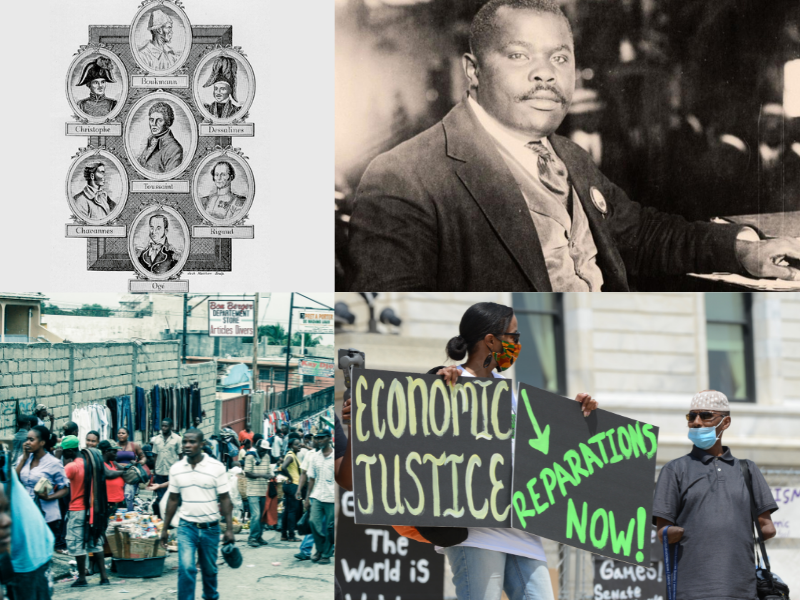

( Juneteenth reparations rally. Image by A1Cafel via Wikimedia Commons )

( Juneteenth reparations rally. Image by A1Cafel via Wikimedia Commons )

In 2021, the descendants of enslaved Black people in the United States was estimated to be 47 million. The importance of economic reparations can be evidenced in the deeply rooted economic disparities among Black populations.

A 2016 study from the Survey of Consumer Finances reported that Black families have 10% of the wealth that White families have, with Black families net wealth being $17,000 in 2016, and White families net wealth being $171,000. A 2019 study by the American Sociological Association also reported that the median White college-educated adult makes 7.2 times more than a median Black college-educated adult.

In the context of slavery, globally, reparations are notorious for being awarded to slave owners. In 1862, slaveowners in the District of Columbia were paid an estimated value of $25 million for the release of more than 3,100 slaves, with enslaved communities offered today’s value of $2683 to permanently leave the United States. 400,000 acres of land, known as the 40 acres and a mule initiative, was designated as a reparative act by Abraham Lincoln after the abolishment of slavery. However, after his assassination in 1885, the act was removed.

In 2021, Thomas Craemer, a professor of public policy, estimated that the value of reparations to be paid to the descendents of enslaved Africans in the United States would equal approximately $20 trillion USD.

Some global communities who have experienced the brunt of US injustice have received reparations. In 2020, the US agreed to pay citizens of Guam reparations for hardships that indigenes experienced at the hands of Japan during the three-year US occupation, including $25,000, $15,000, $12,000 and $10,000 settlements.

From 1978 to 1988, the Japanese Americans Citizen’s League (JACL) campaigned for reparations, in light of Japanese-Americans being sent to concentration camps for three years during WWII. This campaign resulted in $20,000 to each survivor and an apology as part of the Civil Liberties Act, which occurred during the Reagan era.

Others are still campaigning for economic justice. In 2013, fourteen countries of Caribbean Community (CARICOM) issued a joint lawsuit to Britain, France and the Netherlands for slavery reparations.

Reparations for the descendents of African slaves in America has been called for through House Resolution 40 (HR40), a proposal launched by the late Michigan Congressman John Conyers in 1989. In 2021, the House of Representatives voted to progress the commission for full consideration. HR40 was presented at congressional hearings annually for 32 years.

Economic restitution for events like race-based policy brutality in Chicago and the 1923 race-riot as well as the Rosewood Massacre in Florida have been passed, but it is unclear when the US government at-large will take the issue of reparations for the descendants of slavery seriously With the appointment of Judge Ketanji Brown Johnson as the first Black Female Supreme Court Judge, the future of reparations may take center stage again as more diverse representation in governing positions is slowly but surely becoming a reality making room for other catalysts to follow.

Works Cited

https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/garvey_marcus.shtml

https://www.pc.gc.ca/en/culture/clmhc-hsmbc/res/information-backgrounder/Universal_Negro

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/01/27/key-findings-about-black-immigrants-in-the-u-s

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ssqu.12151

https://www.brookings.edu/policy2020/bigideas/why-we-need-reparations-for-black-americans

https://www.ncronline.org/news/people/guam-residents-compensated-war-atrocities-decades-later

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1784-1800/haitian-rev

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-united-states-first-refugee-crisis-180957717

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41716763

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/louisiana-purchase

https://www.britannica.com/event/Treaty-of-Paris-1763

http://www.inmotionaame.org/print.cfm@migration=5.html

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1914-1920/haiti

https://www.history.com/news/reparations-slavery-native-americans-japanese-internment

https://time.com/5609044/reparations-hearing-history

Nana Ama Addo is a writer, multimedia strategist, film director, and storytelling artist. She graduated with a BA in Africana Studies from the College of Wooster, and has studied at the University of Ghana and Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Nana Ama tells stories of entrepreneurship and Ghana repatriation at her brand, Asiedua’s Imprint ( www.asieduasimprint.com ).