Althea Gibson

Long before Venus and Serena Williams, another tall, young Black woman shook up the staid world of tennis with her powerful serve and brilliant play. Althea Neale Gibson was an African American tennis player and professional golfer, and one of the first Black athletes to cross the color line of international tennis. In 1956, she became the first African American to win a Grand Slam event. in 1950 became the first Black tennis player to enter the national grass-court championship tournament at Forest Hills in Queens, New York. The next year she entered the Wimbledon tournament, again as the first Black player ever invited.

Until 1956 Gibson had only fair success in match tennis play, but that year she won several tournaments in Asia and Europe, including the French and Italian singles titles and the women’s doubles title at Wimbledon. She also won the U.S. mixed doubles and the Australian women’s doubles in 1957. That year Gibson was voted Female Athlete of the Year by the Associated Press, becoming the first African American to receive the honor; she also won the award the following year. In 1971 she was elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame.

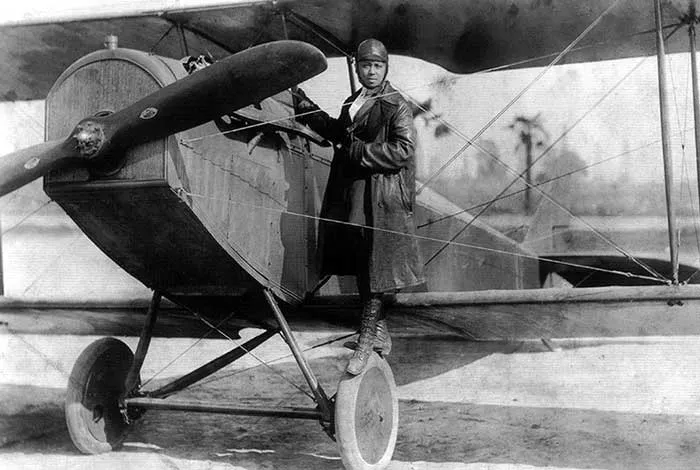

Bessie Coleman

Born to sharecroppers in a small Texas town, Elizabeth “Bessie” Coleman became interested in flying while living in Chicago, where stories about the exploits of World War I pilots piqued her interest. Coleman was an American aviator and a star of early aviation exhibitions and air shows. African Americans and women had no flight training opportunities in the United States, so she saved and obtained sponsorships in Chicago to go to France for flight school. In 1921 she became the first Black woman to earn a pilot’s license. In 1922, she performed the first public flight by an African American woman. She was famous for doing “loop-the-loops” and making the shape of an “8” in an airplane. People were fascinated by her performances, and she became more popular both in the United States and in Europe. She toured the country giving flight lessons and performing in flight shows, and she encouraged African Americans and women to learn how to fly. Fans called her “Queen Bess” and “Brave Bessie.”

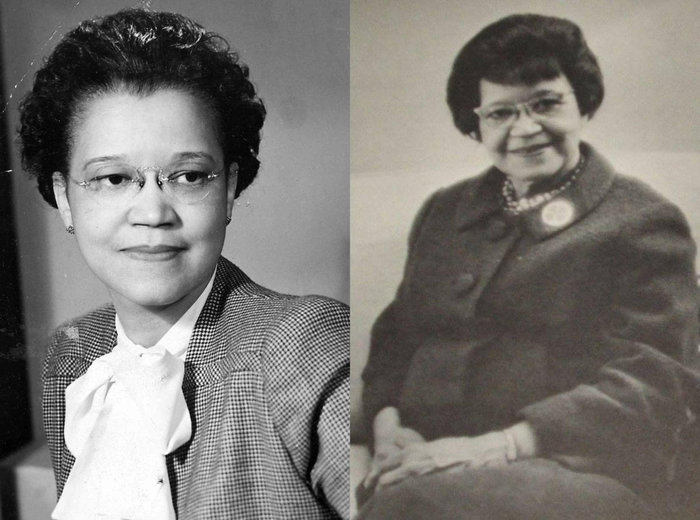

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander was a pioneering Black professional and civil rights activist of the early-to-mid-20th century. In 1921, Mossell Alexander was the second African-American woman to receive a Ph.D. and the first one to receive one in economics in the United States. Alexander accomplished all this while often facing bitter acts of racial prejudice. As a first-year undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, she was told she couldn’t check books from the school library. A dean at the University of Pennsylvania School of Law lobbied against her being selected to join the university’s law review. She persevered and made the law review anyway.

Along with her husband, Alexander fought for Black Philadelphians to be allowed access to restaurants, hotels, and movie theaters. In 1946, President Truman appointed Alexander to be one of 16 members of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights. She was also appointed to the White House Conference on Aging by President Jimmy Carter. In 1951, Alexander co-founded the Commission on Human Relations of the City of Philadelphia. She was a member of the commission from 1952 to 1968. The Sadie Collective was named in honor of Alexander. The organization, formed by two Black women in 2018, encourages other Black women to enter economics and other data-driven fields. The Sadie Collective was named in honor of Alexander. The organization, formed by two Black women in 2018, encourages other Black women to enter economics and other data-driven fields.

Daisy Gatson Bates

Daisy Bates was born in Huttig, Arkansas in 1914 and raised in a foster home. When she was fifteen, she met her future husband and began traveling with him throughout the South. The couple settled in Little Rock, Arkansas, and started their newspaper. The Arkansas Weekly was one of the only African American newspapers solely dedicated to the Civil Rights Movement. The paper was circulated statewide. Bates not only worked as an editor but also regularly contributed articles. Bates became the president of the Arkansas chapter of the National Association for Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1952.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional. After the ruling, Bates began gathering African American students to enroll at all-white schools. When the Little Rock Nine walked into Central High School in 1957, the entire country was watching. Bates selected nine students to integrate Central High School in Little Rock. She regularly drove the students to school and worked tirelessly to ensure they were protected from violent crowds. She also advised the group and even joined the school’s parent organization.

Due to Bates’ role in the integration, she was often a target for intimidation. Rocks were thrown into her home several times and she received bullet shells in the mail. The threats forced the Bates family to shut down their newspaper. After the success of the Little Rock Nine, Bates continued to work on improving the status of African Americans in the South. Her influential work with school integration brought her national recognition. In 1962, she published her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Eventually, the book would win an American Book Award.

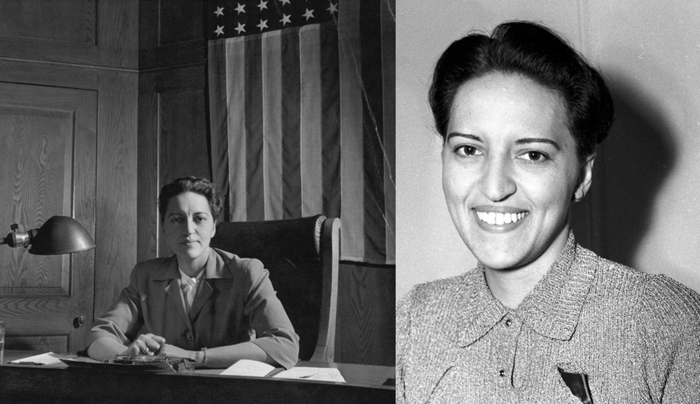

Jane Bolin

Jane Bolin became the first Black woman to break down many barriers during her life. However, the title for which she holds the most recognition is that of the first Black woman judge in the country. The daughter of an influential lawyer, Bolin grew up admiring her father’s leather-bound books while recoiling at photos of lynchings in the NAACP magazine. Wanting a career in social justice, Bolin was also the first Black woman to earn a law degree from Yale Law School, breaking another glass ceiling at the age of 23. Bolin worked with her family’s practice in her home city for a time before marrying attorney Ralph E. Mizelle in 1933 and relocating to New York. As the decade progressed, after campaigning unsuccessfully for a state assembly seat on the Republican ticket, she took on assistant corporate counsel work for New York City, creating another landmark as the first African-American woman to hold that position.

On July 22, 1939, a 31-year-old Bolin was called to appear at the World’s Fair before Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, who — completely unbeknownst to the attorney — had plans to swear her in as a judge. Using her position from the bench as a family court judge, Bolin fought against racial discrimination within the system and was a fierce advocate for children, particularly children of color, whose cases she oversaw. She also changed segregationist policies that had been entrenched in the system, including skin-color-based assignments for probation officers. Additionally, Bolin worked with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in providing support for the Wiltwyck School, a comprehensive, holistic program to help eradicate juvenile crime among boys.

Barbara Jordan

Barbara Jordan showed early interest in public speaking while getting up in front of the Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church as a child, and joining the debate team in high school. After completing studies at Texas Southern University, and Boston University School of Law, Jordan taught at Tuskegee University for a year, then returned to Houston to establish a private law firm. Jordan was an effective campaigner for the Democrats during the 1960 presidential election, and this experience propelled her into politics. In 1962 and 1964 she was an unsuccessful candidate for the Texas House of Representatives, but she was elected in 1966 to the Texas Senate, the first African American member since 1883 and the first woman ever elected to that legislative body. Jordan remained in the Texas Senate until 1972 when she was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from Texas’s 18th district.

In the House, Jordan advocated legislation to improve the lives of minorities, the poor, and the disenfranchised and sponsored bills that expanded workers’ compensation and strengthened the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to cover Mexican Americans in the Southwest. Jordan was part of another historic milestone when she became the first African American woman to be governor of a state -acting as Governor of Texas on June 10, 1972, as part of her duties as the president pro tempore of the state Senate. For her exemplary service to the nation, Barbara Jordan was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

Wilma Rudolph

Born into a family of 22 children and having polio and scarlet fever as a child, Wilma Rudolph persevered to become a world-class athlete. She overcame her disabilities to compete in the 1956 Summer Olympic Games, and in 1960, she became the first American woman to win three gold medals in track and field at a single Olympics and broke at least three world records. Rudolph earned her medals in the 100m, 200m, and 4X100m relay events. Returning home an Olympic champion Rudolph refused to attend her homecoming parade if it was not integrated. She won the Associated Press Female Athlete of the Year award in 1961.

The following year, Rudolph retired from track and field. She went on to finish her degree at Tennessee State University and began working in education. She continued her involvement in sports, working at several community centers throughout the United States. She was inducted into the US Olympic Hall of Fame in 1983 and started an organization to help amateur track and field stars. In 1990, Rudolph became the first woman to receive the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s Silver Anniversary Award. She has said that her proudest legacy is the Wilma Rudolph Foundation, where she helps pair tutors with young children to teach kids about American heroes. In 2004, the United States Postal Service honored the Olympic champion by featuring her likeness on a 23-cent stamp.

Source

Boitumelo Masihleho is a South African digital content creator. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Rhodes University in Journalism and Media Studies and Politics and International Studies.

She’s an experienced multimedia journalist who is committed to writing balanced, informative and interesting stories on a number of topics. Boitumelo has her own YouTube channel where she shares her love for affordable beauty and lifestyle content.