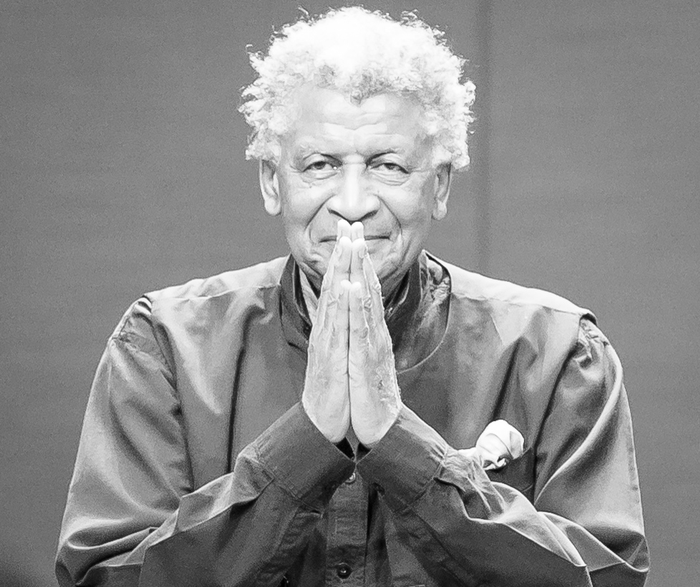

Image by Tore Saetre, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Abdullah Ibrahim, South Africa’s most distinguished pianist, was born on 9 October 1934 in Cape Town. This year marks not only his 90th birthday but also the start of a world tour. Christine Lucia has studied Ibrahim’s work and published research articles about him. We asked her why he is so important.

Who is Abdullah Ibrahim and what shaped him?

Abdullah Ibrahim is the finest jazz pianist-composer that South Africa has ever produced – even in such a jazz-rich country. He is the country’s equivalent of the US jazz star Duke Ellington because his legacy lies not only in his live performances or multiple recordings but also in his large number of compositions.

He was brought up going by the name Dollar Brand and was shaped personally by his mixed-race parentage and by growing up in the mixed-race area of central Cape Town formerly known as District Six. The area was demolished during the 1970s by the White minority apartheid regime and 60,000 people were forced to live far outside Cape Town on the Cape Flats. He was shaped by this violent political landscape of racism and oppression. As a young man, he was also shaped by his conversion to Islam in 1968, which is when he took the name Abdullah Ibrahim, and by his practice of martial arts and zen (a form of Buddhism).

He was shaped musically by the variety of different music he heard in Cape Town. These include jazz, the Cape carnival troupes known as klopse, and the music of people who practiced the Sufi branch of Islam in the Cape and whose chanting, drumming, and dancing he witnessed. He was influenced by the Christian hymns played by his mother and other music he heard at the African Methodist Episcopal Church, which included gospel and African-American spirituals. He was shaped by jazz and dance band music and by African traditional music from Lesotho, the country of his father; even by Indian classical music and western art music.

What distinguishes his work?

His work as a composer is distinguished by its pianism and its international flavor with a strong dose of South Africa. He has also played flute, cello, and soprano sax – which gave him insights into ensemble playing – but he is above all a brilliant pianist.

He has written great tunes but it is his harmonies, textures, colors, rhythms, phrasing, and pianistic flow that make his compositions outstanding. His recordings are distinguished by the huge development of jazz style and treatment within them over 70 years. His music of the 1960s contains some avant-garde (experimental) sounds; his music from the 1970s and 1980s is full of references to Africa in the titles of pieces and within the music itself. In the 1990s, with the fall of apartheid, Ibrahim’s music took on a more sentimental mood. In later life, he became more interested in arrangements, and in orchestrating his music.

Another thing that distinguishes his career is that while he has always written new pieces he has also constantly reinvented and reimagined old ones, mainly through his playing and often in his solo playing. It is as if he is remembering through his hands.

Memory plays a key role in all his music: he is always looking back, and sometimes he finds something there that helps us face the future. This doesn’t just apply to pieces, it applies to the way he plays. He could always be quite sparse, but in the past 10 years the pared-down simplicity of his playing, its clean lines, is more introspective, more philosophical.

In the 1970s and 1980s, he was the darling of the anti-apartheid movement because of the promise of freedom in his music and his going into exile. The same music speaks now to scattered hopes, which makes it almost unbearably poignant.

You can hear this in his rendition of Wedding on his 2021 album Solotude. Listening to this, people of my generation remember those fierce solo performances he gave when this song first appeared in the 1970s, those huge build-ups on the keyboard that ended very loud, both hands playing rapidly repeated chords (his trademark tremolo). It sounded like a hymn to freedom. Now, when playing this same piece his hands trace notes sporadically and gently on the keyboard, like a ghost, with the tune in his right hand occasionally ahead of the change of chords in the left. Minimal.

Abdullah Ibrahim in 2016. Photo by Tore Saetre, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

What are his career highlights?

The album Jazz Epistle – Verse 1, made in 1960 with Dollar Brand, Mackay Davashe, Hugh Masekela, Jonas Gwangwa, and Kippie Moeketsi, a quintet of the foremost jazz musicians of the day, was among the first Black jazz recordings in South Africa. It was also a milestone in the careers of all participants, several of whom went into exile.

Dollar Brand and his wife Sathima Bea Benjamin went into exile in 1962, at first in Zurich. While he was there, Duke Ellington heard him play in 1963 and immediately produced the album Duke Ellington presents The Dollar Brand Trio.

In 1965 the couple moved to New York, which was their home for many years with only occasional trips back to South Africa. They founded their record label in 1981, Ekapa (The Cape), although he continued to record with the Enja label. Ekapa also became the name of the septet he formed in 1983. He composed music for the award-winning film Chocolatin 1988.

In 1990 he gave triumphant “homecoming” concerts when Nelson Mandela and other anti-apartheid activists were released from prison. In the 1990s, now spending part of his time abroad and part at home, Ibrahim began expanding his sound world into orchestral arrangements of his music, performing his African Symphony in Munich in 2001. In 1994 he performed, memorably, at Mandela’s presidential inauguration. There have been many other memorable concerts and awards in his recent career. His “home concert” online during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals his more intimate side.

Is it common to be performing at 90? What’s his secret?

In some professions, like conducting, yes. But it’s rare. Great pianists of the past played on into their 90s but made more and more mistakes playing the same music the same way. Abdullah Ibrahim has pared down his playing as he has grown older and distilled it. Like well-matured brandy, you only need a sip and everything is there.

Of course, he could also be minimal in his youth, but now it’s for a different reason because he’s in a very different space. He has become more and more zen. I imagine him as very disciplined, which I am sure has helped him maintain his health and strength as an artist. His 2024 tour looks punishing, but he is taking plenty of breaks in between concerts in Italy, South Africa, Germany, and the US. Abdullah Ibrahim ends his world tour in Bavaria, where the final concerts are scheduled to be given immediately after he turns 90, on 9 October.