A significant number of pioneering Black men and women have helped change the course of healthcare and race relations in the United States since at least the early 19th century. They invented first-of-their-kind medical devices, developed innovative surgical procedures, paved the way for improved patient access to quality care, and raised awareness about quality-of-life issues. These clinicians, researchers, activists, and advocates championed and advanced medicine in this country and beyond. Their legacies live on in hospitals and clinics, doctors’ offices, schools, universities, and research laboratories. From medical advancements to advocating for a more equitable system, these healthcare trailblazers deserve their flowers.

Dr. Patricia Bath

Dr. Patricia Bath was a Black woman ophthalmologist who was a trailblazer for the profession. In 1974, she was the first woman ophthalmologist to be appointed to the faculty of the University of California at Los Angeles School of Medicine Jules Stein Eye Institute. She decided to study chemistry and physics at Hunter College in Manhattan, earning a bachelor’s degree there in 1964. She received her medical degree from Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., interned at Harlem Hospital from 1968 to 1969, and completed a fellowship in ophthalmology at Columbia University from 1969 to 1970. In 1976 she was a founder of the nonprofit American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness, along with Alfred Cannon, a psychiatrist, and Aaron Ifekwunigwe, a pediatrician.

In the early 1980s, her work with cataract patients and related research led her to envision a method of using laser technology to remove cataracts, which cloud the lens of the eye. In 1983, she was the first woman to chair an ophthalmology residency program in the United States, and in 1986 she discovered and invented a new device and technique for cataract surgery known as laserphaco. When she first conceived of the device in 1981, her idea was more advanced than the technology available at the time. It took her nearly five years to complete the research and testing needed to make it work and apply for a patent. Today the device is used worldwide.

In 1993, Bath retired from UCLA Medical Center and was appointed to the honorary medical staff. After that, she advocated for telemedicine, the use of electronic communication to provide medical services to remote areas where healthcare is limited. Her greatest passion was fighting blindness until she died in 2019.

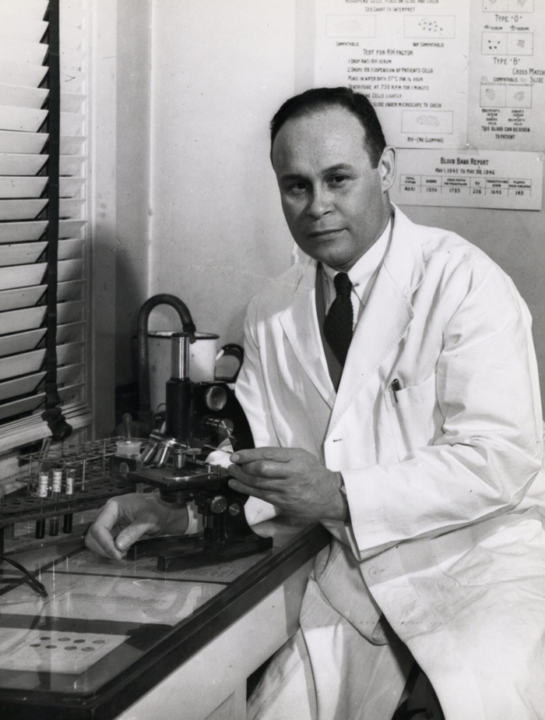

Dr. Charles Drew

While attending medical school at McGill University in Montreal, Charles Richard Drew, a native of Washington, DC, developed an interest in blood transfusions and the properties of blood. Dr. Drew is referred to as the ‘father of blood banking’ due to his critical contributions to the development of a safe, effective, blood collection system in the U.S. As a surgeon, he came up with innovative ways to store blood plasma in blood banks. Plasma can be preserved or “banked” much longer than whole blood. Drew discovered that the plasma could be dried and reconstituted later.

His thorough investigation of the medical literature, practices among the early blood banks, and evaluation of multiple variables allowed for optimization of whole blood collection and storage. This resulted in Dr. Drew creating standardized processes for donor screening and testing for infectious diseases, blood processing, and training of those collecting the blood. These standardized, reproducible processes have led to what we see today in blood banks worldwide. As a result of his work, he received his Doctor of Medicine in 1940 for his dissertation ‘Blood Banking.’ Dr. Drew created a program through the American Red Cross to collect and freeze-dry plasma for use by American forces during the war. This became the National Blood Donor Service, which subsequently developed into the American Red Cross Blood Services which collects approximately half of the blood transfused in the U.S. today.

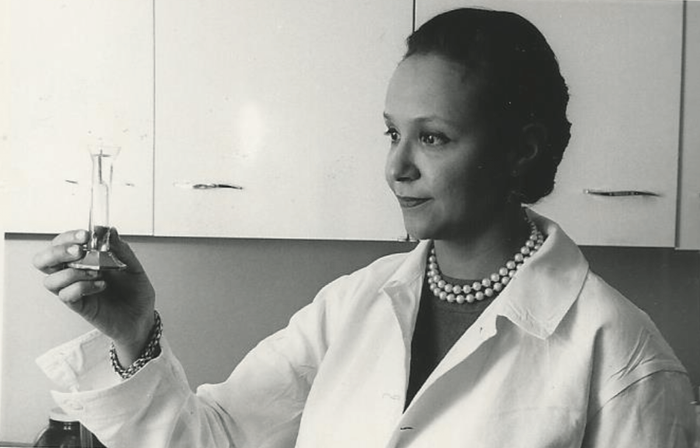

Dr. Jane Cooke Wright

The daughter of one of the first African American graduates of Harvard Medical School, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright, grew up with a keen interest in healthcare. Her father, Dr. Louis Wright, was also the first Black doctor appointed to a staff position at a municipal hospital in New York City, and in 1929, the city hired him as a police surgeon — the first African American to hold that position. In 1949 Wright began the cancer research that would make her one of the leading names in the field. Working initially with her father, she made numerous improvements to chemotherapy treatment including using nitrogen mustard agents to treat sarcoma, leukemia, and lymphoma.

She pioneered the use of patient tumor biopsies for drug testing against various tumors, and she developed a non-surgical procedure using a catheter to deliver chemotherapy drugs to previously inaccessible tumors in the kidneys and spleen. In 1955, Dr. Wright became an associate professor of surgical research at New York University and director of cancer chemotherapy research at New York University Medical Center and its affiliated Bellevue and University hospitals. In 1971, Dr. Jane Wright became the first woman president of the New York Cancer Society. After a long and fruitful career in cancer research, Dr. Wright retired in 1987. During her forty-year career, Dr. Wright published many research papers on cancer chemotherapy and led delegations of cancer researchers to Africa, China, Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union.

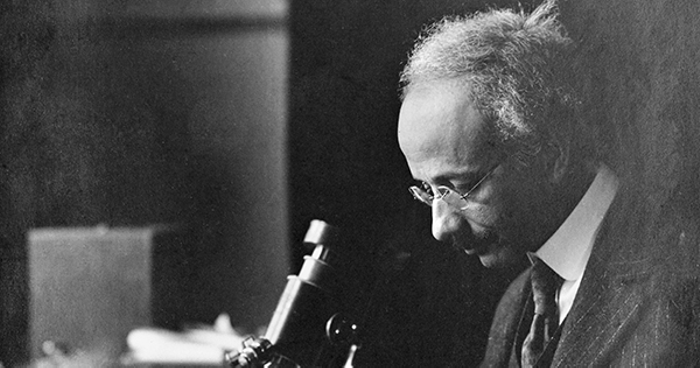

Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller

Dr. Solomon Carter Fuller was a pioneering Liberian neurologist, psychiatrist, pathologist, and professor. Born in Monrovia, Liberia, he completed his college education and medical degree in the United States. Dr. Fuller came to the U.S. as a teen to study medicine and to return to Liberia to become a medical missionary like his maternal grandparents. Dr. Fuller received his medical degree from the Boston University School of Medicine. He completed a two-year internship at Westborough State Hospital in Massachusetts and began his professional duties as a hospital pathologist and an instructor of pathology at Boston University.

Fuller faced discrimination in the medical field in the form of unequal salaries and underemployment. His duties often involved performing autopsies, an unusual procedure for that era. While performing these autopsies Fuller made discoveries that allowed him to advance in his career as well as contribute to the scientific and medical communities. In 1904, Dr. Fuller sought to improve his laboratory and diagnostic skills by studying in Europe. He was one of five foreign visiting students selected by Dr. Alzheimer to work as a graduate research assistant. Dr. Alzheimer was studying what was called presenile dementia at the time.

Fuller’s work as a pathologist on Alzheimer’s was truly groundbreaking. His work also helped reframe the conversation around the disease. Dr. Fuller published what is now referred to as the first comprehensive review of Alzheimer’s disease in 1912. In it, he wrote an account of his own patient with Alzheimer’s disease, said to be the ninth case ever discovered. He also included the first English translation of the Alzheimer’s case of Auguste Deter, the woman first diagnosed with the degenerative disease. He also published his own 1912 work in German. He recognized that it was not caused by insanity but by the physical decay of the brain.

Faye Wattleton

A renowned advocate for reproductive rights, Wattleton holds a bachelor’s degree in nursing, a master’s in maternal and fetal infant care, and a certification in midwifery. She was the first African American, and youngest president of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, and is credited with developing the organization’s extensive national grassroots advocacy network. By the time she left the organization, it had grown to become the nation’s seventh-largest nonprofit organization with an aggregate budget of $500 million and 170 affiliates in the United States.

At 16, she enrolled at Ohio State University, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in nursing. She later attended Columbia University, where she pursued a master’s degree in maternal and infant care. Wattleton began her nursing career as an instructor at Miami-Dade Hospital in Ohio, teaching nursing obstetrics and labor and delivery. While working toward her master’s degree, she interned at a hospital in Harlem. There, Wattleton saw female patients with life-threatening side effects of unsafe abortions. During her time at the hospital in Harlem, she learned about many aspects of unwanted pregnancy. Approximately 6,500 women were admitted for complications from incomplete abortions during her time there.

Wattleton has received numerous awards and honors, including the American Humanist Award, the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation‘s Humanitarian Award, the American Nurses Association’s Women’s Honor in Public Service, and the Jefferson Award for the Greatest Public Service Performed by a Private Citizen. Throughout her career, Wattleton has been awarded fourteen honorary degrees. In 1993 Wattleton was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, and in 1996, published her memoirLife on the Line.

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston

As a young student, Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston faced several adversities, like poverty and prejudice, but had her heart set on becoming a physician. She has dedicated her career to medical care for poor and minority families and campaigns for healthcare equality for all Americans. Her 1986 study of sickle-cell disease led to a nationwide screening program to test newborns for immediate treatment, and she was the first African American woman to direct a public health service bureau (the Bureau of Primary Health Care in the United States Department of Health and Human Services).

In 1986 Dr. Gaston published the results of a groundbreaking national study that proved the effectiveness of giving SCD children long-term penicillin treatment to prevent septic infections. Her study showed that babies should be screened for SCD at birth so that preventive penicillin could be given right away. The study resulted in Congressional legislation to encourage and fund SCD screening programs nationwide. Within one year, forty states had begun screening programs. One of the most important conclusions of her work was the ease with which the complications of Sickle Cell Disease could be avoided with early treatment, a life-saving practice that became a central policy of the U.S. Public Health Service.

Dr. William Coleman Jr.

Dr. William G. Coleman Jr. was the first permanent Black scientific director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Research Program (IRP). He directed the NIH’s National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. He took the leadership on transdisciplinary research that focused primarily on the biological and non-biological determinants of health disparities and their influence on the outcomes of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes, among other chronic diseases.

Throughout his career, Coleman made seminal contributions to a type of bacteria that causes infection in the stomach and is associated with gastritis, ulcers, and gastric cancers. These infections affect millions of Americans and are more common among Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic blacks than in non-Hispanic whites. Under Coleman’s leadership, NIMHD’s intramural program focused on three scientific research areas for which there are significant health disparities: cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes.

Dr. Ruth Ella Moore

Dr. Ruth Ella Moore was a bacteriologist known for her work on blood types, tuberculosis, tooth decay, and gut microorganisms. She completed her dissertation work on tuberculosis at Ohio State University in 1933, becoming the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in the natural sciences, as well as the first African American of any gender to earn a PhD in Bacteriology. Ohio State University was one of the few universities in the United States admitting Black students at the time. Throughout her career, she was a member of the American Public Health Association and the American Society of Microbiology, which she joined in 1936. Moore was the first African-American to join the American Society for Microbiology.

She later became a professor at Howard University in 1940, and department head in 1952, the first woman to head any department at Howard. One of her first acts as Head was to change the department name from Department of Bacteriology to Department of Microbiology. She retired in 1973. Moore was also an accomplished seamstress and garment designer. Her garments have been exhibited at Ohio State University where she earned both her undergraduate and graduate degrees. Moore was also awarded two honorary degrees from Oberlin College and Gettysburg University around the time of her retirement from Howard University in 1973.

Boitumelo Masihleho is a South African digital content creator. She graduated with a Bachelor of Arts from Rhodes University in Journalism and Media Studies and Politics and International Studies.

She’s an experienced multimedia journalist who is committed to writing balanced, informative and interesting stories on a number of topics. Boitumelo has her own YouTube channel where she shares her love for affordable beauty and lifestyle content.